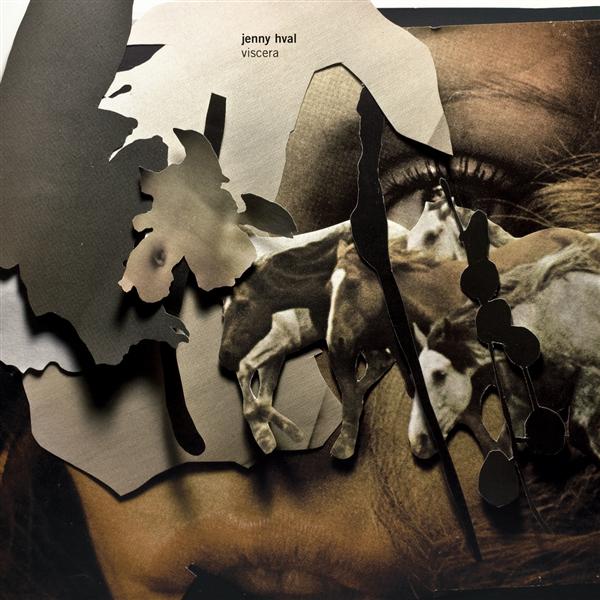

Jenny Hval

Viscera

(Rune Grammofon; 2011)

By Joel Elliott | 12 August 2011

“I arrived in town with an electric toothbrush pressed against my clitoris.” So begins Jenny Hval (aka Rockettothesky)’s debut under her given name, an ode, in her own words, to “flesh and traveling.” The power dynamics of modernism implicitly suggest any expression of female sexuality is confined to pure physicality (or a commentary on those power relations themselves), while the Marquis de Sade and Man Ray have the privileged distinction of representing vision and self-hood, heroic concepts not limited to the body but liberated by it. Hval’s auto-erotic masterpiece ignores this dichotomy, making the poet both subject and object in a journey where the intimately familiar becomes alien and vice-versa. Rarely as confrontational as it seems on paper (vagina dentata references and all), Hval seems unconcerned with being looked at or looking back, but looking inward.

“Engines in the City,” with all its mechanized sexuality, could be the grounds for a Cronenberg dystopia, but ends with the soft tremble of a body that has learned how to vibrate even after the batteries of the toothbrush die out. Hval layers multiple harmonies over each other that intersect at a point in the air just outside of her, where bodies “silently brush against each other.” This is and isn’t a typical Rune Grammofon release: it seems to come from the same universe so well cocooned by the pallid shapes of its own environment that it doesn’t seem to need light or oxygen. Helge Sten (aka Deathprod), who cast his shadow over the mutant jazz of Supersilent, produces. And yet, along with Phaedra’s recent The Sea, it seems to represent a new turn for the label, shepherding Scandinavian musicians interested in radical ways of channeling older, more pastoral sounds. Hval is Norwegian, but her music seems to absorb other points along the same latitude: at various times it seems to echo British and Irish folk and even the sounds of the Canadian East Coast, as if all wind-swept rocky shores carried the same vibrations.

But like the more abstract corners of Linda Perhacs or Mary Margaret O’Hara, Hval is more interested in the infinite variations that folk melodies allow, stretching them out to test how long they take to collapse. Her sense of restraint is extraordinary, only allowing the expected vocal release (which she proves wholly capable of) after each track has shifted through layers of unfolding and awakening. The peripatetic movements of “Golden Locks” are nothing short of cinema, cycling through unresolved chords that dance through the streams of banal conversation (a more convincing musical vernacular for complex prose you will not find in any of the last two Joanna Newsom albums) before escalating into a fever dream. Hilariously, the only other character to appear on the album is a man who tells the narrator she needs to get laid, to which she responds by hallucinating her golden hair melting into piss and turning into a golden shower, a mix of self-deprecation and phoenix-like transformation that knowingly points towards the boredom (what the Surrealists called “miserablism”) which makes art necessary.

The fact that the music reflects so perfectly the thematic obsessions at the heart of this album is surprising in a genre which even now seems to always tilt towards lyricism or environment but rarely holds both in equilibrium. As an album about traveling, Viscera rejects any kind of linear narrative development in favour of free play, literally on “Blood Flight,” where body parts switch places and every pore grows eyes and fingernails reach out of the sockets. She describes her cunt growing teeth and her clitoris as a one-eyed sphinx: “So many blind years / Acting Oedipus,” simultaneously evoking and rejecting Freud, as if it was the myth itself which represses the id. In the climax she imagines her blood escaping her body through the neck, her voice continually rising, stretching her vocal cords as thin as the stream which takes her up with it. Musically the track comes as close to conventional post-rock as anything else here—all galloping toms and simple, off-beat rooted intervals on guitar—but her voice carries the track so far the rest of the band hardly needs to change chords. And rather than exploding and burning out, the track ends with Hval and her blood spread across the sky while the music slows to a crawl and her voice dissipates—simultaneously the awareness of the dream and the refusal to wake up.

Some of the arrangements seem so unlikely that they add a dimension that neither the lyrics nor the music on its own could achieve. The closing title track, in which the narrator is unable to do yoga because all of her insides are falling out of her mouth, superficially recalls the gross-out opening short story from Chuck Palahniuk’s Haunted (the one that supposedly caused a significant portion of the audience at a reading to faint). And yet while Palahniuk’s prose juts tediously from shock to the mundane, everything on “Viscera” flows seamlessly: one minute she’s doing a downward dog, the next her “vocal cords flow like seaweed.” It seems all the more uncanny because the whole thing could pass for a Faiport Convention song if you weren’t paying attention, only close listens revealing how multiple vocal tracks seem to gently steer the song away from natural harmonies into something a little weirder. This is the missing link between Orlando (which Hval cites as a major influence) and Bataille, the strength of the possible as a commentary on the written word itself.

Sometimes the subtext is nearly unbearable. “How Gentle,” in which Hval sees a deep body of water as a womb, is mostly just her voice, a painfully simple picked acoustic guitar, and a melody not unlike “The Wind that Shakes the Barley,” but with the glassy production, subtle shifts in tempo and notes which precariously linger, the whole thing has the psychosexual heft of an early Genesis song. In contrast “This is a Thirst” echoes the combination of baroque vocals and electroacoustic instrumentation that David Sylvian has become infatuated with as of late. The background is not unlike the anonymous murk of Supersilent’s 9 (2009), but is far more effective as a reflection of desire, Hval calling out for “Honeydew,” until she summons a single shimmering mandolin chord like a drop of water in the desert. That mostly static drone seems more and more essential every time I listen to it: providing the minimum amount of momentum while allowing every crack from Hval’s vocal cords or drop of saliva on her tongue to hang unobstructed in the air.

Nothing epitomizes Hval’s obsessions quite as fully as “Portrait of the Young Girl as an Artist,” which flows from an almost spoken-word opening to the only complete release of all the pent-up energy sublimated elsewhere. The song takes that most heroic male-centred pillar of modernism, Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man and inverts the formula, suggesting not an artist struggling through the social restraints and misguided fears of youth, but a woman for whom art is the opportunity for the continual resurgence of youth and (re)discovery. Its combination of naive and radical sexuality reminds me of Carolee Schneemann’s experimental film Fuses (1967), which similarly dissolves power within the microcosmos of the bedroom, inverting and reverting hers and her male partner’s position until no one is dominant, and both become voluntarily submissive to the tumble dryer of erotic bliss. Like Schneemann, Hval asks “which is up and which is down,” contemplating the definition of erections, spatiality and movement in relation to the body.

Hval compares thighs to train tracks, and desire as a “train running into a tunnel,” but over the course of the track the obvious symbolism is dissolved into a series of overlapping images and associations. Like all great poets, she teases with meaning but thwarts interpretation whenever possible. What is visceral is both of the internal organs, and what is most immediate, and therefore irreducible. Likewise the main thrust of Viscera is the cycle of flesh continually transcending into something deeper and universal then being reduced back to pure body. Threatening to dissolve into an undifferentiated mass than gathered, coiled up and collected into something private and mysterious again.