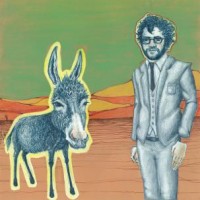

John Wesley Coleman

The Last Donkey Show

(Goner; 2012)

By Maura McAndrew | 26 May 2012

The first and final songs on John Wesley Coleman’s fourth album, The Last Donkey Show, begin with the same lines: “Close the door / I don’t love you anymore.” In fact, these tracks, “My Grave” and “Flower in the Dark” respectively, have all the same lines—because they’re the same song. One might not notice right away, so different are they in style and attitude, but those opening lines, like a kick in the gut, are impossible to ignore. While “My Grave” disregards the heaviness of such a beginning, kicking off like a party, all wild whoops and upbeat organ, by the end of the record the party’s over; its reprise, “Flower in the Dark,” replaces bravado with melancholy. Over languishing guitar lines and pedal steel, Coleman slowly sings those same lyrics like a man realizing what he’s lost.

There, in two bookends, John Wesley Coleman (whom I had never heard before) converted me to fandom. I could listen to a whole album’s worth of just this one song, laid out like a Choose You Own Adventure of the post-breakup emotional landscape. Still, there’s a lot more to The Last Donkey Show: miles of great genre-hopping pop-Americana; trashy poetry with emotional resonance.

Coleman, little-known outside his Austin enclave, recorded Donkey Show both in Texas and Oakland, CA with producer Greg Ashley (the Gris Gris). When it came out a few months ago to little buzz, the question has occurred to me: why isn’t Coleman more of a household name (besides the fact that his name itself is part Bob Dylan album, part Christian-country singer)? Like labelmates Limes, he’s the sort of locally-focused eccentric who doesn’t seem to fit neatly into any national niche, and his past records have been a little wild and sloppy, made for pleasure, not prominence. The Last Donkey Show should position him to collect more of a following, because though it gives off the same familiar aura of sloppiness, it’s stealthily under control in ways he’s never afforded before, full of songs with purpose and motivation. Coleman’s exploring, surely, but he never abandons a sure-footed consistency, and the record works wonderfully as a whole.

Coleman adheres mostly to retro, doo-wop melodies sped up with a touch of rockabilly and soul, and there’s more than a hint of Elvis Costello in tow. “The Last Donkey Show,” “Hanging Around,” and “Animal Bed” (with its Four Seasons-like backing vocals) are all utterly charming variations on this sonic theme. “Hanging Around” in particular has a mod bent, which is developed more fully on the Ashley-penned “Misery Again,” which takes its cue from Beatles songs like “Maxwell’s Silver Hammer” and “Rocky Raccoon.” The best tracks are those that take things to further into Motown/soul territory, such as “Don’t Waste My Time” and “The Howling,” which plays like a lost soul classic, all saxophone and Coleman’s committed, rupturing vocals. Yes, the man knows how to howl.

He also seems to move fluently between genres: “She’s Like Dracula” is a fun riff on Lou Reed/Tom Petty rock, though earlier songs like “A Clown Gave You a Baby” and “Virgin Mary Queen” that stick to more straightforward garage rock are more memorable for their Bukowski-esque imagery than for their melodies. “Running into the Bulls,” a girl-guy duet in the vein of Beat Happening, is the only song on the record that I’d be at all inclined to skip—not bad, but the chosen genre doesn’t really suit Coleman’s energy. And so it drags.

“Running into the Bulls” is useful, however, as a lead in for the record’s best, the beautiful “Flower in the Dark,” an abstract meditation on, well, the end of all things. Coleman sings in his nasal, Neil Young-ish voice about wanting to go home, “back to where [he] came from.” Gliding on a gorgeous pedal steel, he closes: “Oh darling / You carry me through / You’re my flower in the dark.” He’s not goofing around here like he is throughout a lot of the record (with pre-song giggles to prove it); rather, “Flower in the Dark” grounds the whole enterprise, managing to reveal hidden depths to what came before. Sadness and loss resonate in the record’s final notes, and it becomes clear, then, that the only thing to do is to flip the record and start all over again with the exact same words.