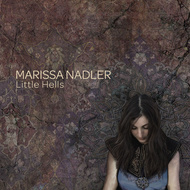

Marissa Nadler

Little Hells

(Kemado; 2009)

By Chet Betz | 4 March 2009

Having her little world introduced to the majority of us by 2007’s Songs III: Bird on the Water, Marissa Nadler’s playing a game with our expectations, seeing how much of the same and how much of something new will she have to give to keep us interested. Little Hells inhabits that same little world, this time with a series of small dark revelations upturned like the worm-ridden bellies of rocks. We know the shtick: languid gothic folk centered ‘round the gorgeous gorgeousness of Nadler’s vocals and produced by the ether—aesthetic inevitably determined by the singular dimension of her songwriting. And yet this record feels like a subversion of past romanticism…plus, the beginning of “Mary Come Alive” sounds like Portishead’s “Machine Gun.” That doesn’t last long, the electro snare hits giving way to the roll of toms and notes plucked with precision yet bleeding plasma; the thing is, Nadler’s never sounded this sinuous, her more fulsome arrangements never this sleek and integrated, a triumph echoed later by the even better “River of Dirt.” On these two songs Nadler and her collaborators (producer Chris Coady, drummer Simone Pace, guitarist Dave Scher, lots-of-stuff Myles Baer) have found a way to broaden the expanse of the simple undulations at the base of her songs, bulking the notes up into rigid forms with glutinous texture and intimately coupling that with propulsive percussion. It’s, like, awesome. There’s no space rock axe scorcher shit (as in “Bird on Your Grave” from Songs III) thrown on top because Nadler’s sound no longer has room for any exoskeleton. This music’s growing from within.

I have to hate the parts where wordless vocals from Nadler recall the Edward Scissorhands soundtrack and “The Hole is Wide” is a fairly useless translation of her guitar playing to blocky piano chords—over which she manages to obsess, once again, about some girl named Silvia. And the fact of that matter is that “Mary Come Alive” and “River of Dirt” are as far as Little Hells pushes, most of the rest falling into a more familiar middle ground where Nadler reverts to her songwriting as aesthetic and lets the accompaniment just find its place rather then letting it push her to any more new discoveries. But the places already settled still sound wonderful, be it the title track with its miniature crescendos or the elegant reserve of “Ghosts and Lovers,” wherein a hundred Plath-isms feel validated by the pallid grace endowed them through Nadler’s music and voice.

And everything’s in its right place. Looking at the most recent release of another indie folk songstress, Neko Case, raises an interesting comparison. After preliminary listens Middle Cyclone feels a bit off the cuff, some songs unsurprisingly beautiful individually but the whole thing feeling a bit rote and scattered compared to the seriously conceptual Fox Confessor Brings the Flood (2006). Just call that first impressions; still, the point is that Nadler’s done the reverse of Case. Songs III played out like an anthology, right down to its title, whereas Little Hells goes beyond just the songs themselves. At the beginning there’s the pining for an ideal of love maybe lost (“Heart Paper Lover”) and some hope for redemption (“Rosary” and “Mary Comes Alive”) but then the title track springs its somber insight (“Soft to a fault / she believes the hardest things of all / True love never did exist at all / She lives in a dark cloud with little hells”), clinging to the faintest hope of going back to “the days of color.” From there it’s a steady descent: “Ghosts and Lovers” draws a clear parallel between bondage spiritual and sensual; “Brittle, Crushed & Torn” shows Nadler broken, her fate seemingly sealed; the little hells she creates for herself separate her from others, the only person she reaches out to being the other “Loner” who is “filled with sin”; so she finally, unhealthily copes with her loneliness by taking on the role of a “Mistress.”

But, unhealthy or not, “Mistress” is the happiest Nadler sounds on the album, the music relatively light, a stark contrast to the foreboding keyboard tone of the opener with its desire for “true love.” Nadler’s quite personal in the way she displays how we’re creatures prone to finding comfort in the meaningless filth that inundates our lives, how our little hells become our homes. As C.S. Lewis once put it and as I paraphrase all the time, we’re like children content to play in the mud when our parents call for a trip to the beach—us little pigs having no concept of what the beach even is. On “Mistress” Nadler chooses to idealize the mud, to treat it like the shore. And Nadler’s not as unequivocal about this idea as Lewis is, which makes her take a bit easier to feel. Along with the stylistic push, all this context makes “River of Dirt” the album’s most wrenching moment, where Nadler gives up on the dreams of her youth and yearns for absolution by dust and fire, by the body laid down to rest in the place it came from.

Little Hells is a soft tremble through the air as fantasy and reality grab a girl on either side and calmly tear her in two.