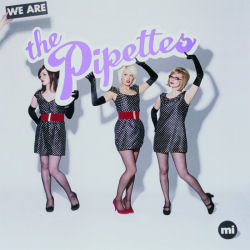

The Pipettes

We Are The Pipettes

(Memphis Industries; 2006)

By Aaron Newell | 8 August 2006

Helene Cixous is a celebrated French philosopher, writer, and theorist who is well-known for her essay “The Laugh of the Medusa.”

In this essay, Cixous lashes out against a male-dominated academic literary tradition, and states that women should not be bound to write in the predominately “male” academic style that features “male” symbolism and “male” imagery and “male” use of language. Cixous argues that these various malenesses are regretfully fundamental elements of “literature” that laid the foundation for the construction of the canon as a misguided organ of institutional sexism. Cixous posits that, as a result of the perpetuation of paternalist society as manifested in academe, women have been forced to express themselves with a muted and transfigured voice, and have never been given the opportunity to communicate a true, unfiltered “female” perspective, thereby further perpetuating gender iniquities and misunderstandings between the sexes and, worst, inhibiting the woman’s understanding of herself. Cixous therefore claims that women have traditionally been writing male ideologies and male language without knowing it, and subsequently urges women to break out of this inhibiting cycle: “Censor the body and you censor breath and speech at the same time. Write yourself. Your body must be heard.” This is not about farting, and don’t you even dare notice the fact that Professor Cixous firmly entrenches herself within the same paternalistic tradition that she bemoans, thereby accidentally arguing that her very piece de resistance is subject to the same invisible phallo-forces that she rages against. She seems to ignore the fact that such forces are inescapable, failing to acknowledge Louis Althusser’s concept of “Ideological State Apparatuses,” which are Wildean opiates-of-the-masses perpetuated by the Ruling Institutions in order to ensure that the State retains its position as the most influential and powerful institution in society, which essentially infinitely perpetuates institutional sexism, as the State was organized by men at its inception, and has always been predominately helmed by men since, natch.

I will abandon my discussion of Wilde and Althusser here, as it is perhaps more apropos for a Jessica Hopper-lead panel discussion with Stephen Merritt and Boots Riley. Or perhaps because, to people interested in We Are the Pipettes, all that sort of hyperanalytical gobbledygook (spellcheck says I spelled that correctly, and on my first try; spellcheck says I spelled spellcheck wrong, however) should mean dick all.

If you’re sensitive to that sort of thing, it’s obvious that the Pipettes’ gestalt begs you to feministize the what fuck that they have going on, but it’s arguably too complicated to pick apart. Check the seesaw: you have a trio of young women who all wear a “uniform” polka-dot dress, without which dresses they are not seen (allowed?) in public. The details of the band’s origin vary per source, but it is generally agreed that some assembly was required, and while the masthead is the Gwenno/Becki/Rose trinity, the band officially has seven members: three female Pipettes and four male “Cassettes,” a Pipette subculture, who play back-up band but don’t talk to press (Wikipedia, as usual, gets to the facts: “The male backing musicians… rarely appear in interviews or promo photos, adding mystique and emphasising the role of the singers”). The band has been referred to as a “project” that was spearheaded by Brighton music promoter “Monster” Bobby (guitarist for The Cassettes), and its name is a direct reference to the fact that the “project” is his “science experiment” – a test-tube baby – the “image” being a key part of the potion. The mode of harmonizing, the choreography, and the general get-up is a transplant from the ’60s, when the Shirelles were singing about being “Putty (in your hands),” but the songwriting is certainly not: “I don’t want you, I don’t want you, leave me alone, you’re just a one night stand.” That’s more parts Weezy, less parts sock-hop.

What keeps the band from being a Brighton-based redux of Broken Social Scene, however, is the delegation of songwriting duties, especially in light of the content, especially especially in light of the tradition that they’re reviving. Currently both the Pipettes and the Cassettes share co-writes (Becki did “One Night Stand,” Rose did “Sex,” bass player Jon wrote “Pull Shapes”). The earlier material, however, was the work of Monster Bobby alone. So while you’ll get lines like “Give us a ship and we’ll man it… Lend us some film, we’ll be candid / Give us the wheel / and make us a meal… We’re the prettiest girls you’ve ever met” fetchingly penned and gleefully smirked out by three uniformed, synchronized, wiggling guinea pigs, commands like “Dance with me, pretty boy, tonight” come straight from some twenty-something dude who thought it would be a fun idea to have his Pips sing something like that, ‘cause it’s super cute for polka-dotted twenty-something girls with retro haircuts singing revamped ‘60s girl-group songs to actually ask the boy to dance, because he’s the pretty one. And the galaxy head-butts itself.

So the deal is, for every nuanced and orchestrated string-pull where the band could easily be called the Puppets, there’s this labyrinthine process of production and collaboration churning in the background, shutting out any argument that, yeah, this is some pure Riot Grrrl shit or, conversely, that this is indeed opportunism bedazzled with sexist overtones, submissive siren front-women, and red tights. This makes the band not just cute (a sexist term, if you want to be a jerk), but interesting, since the holistic Pipettes “thang” is essentially impenetrable. Moreover, if you’ll read any interview, Rose will give you like forty-seven good reasons why the Beatles are the devil, which is not something that Jessica Simpson ponders in between worrying about how she’s going to practice her slow-running for the opening credits of the Baywatch movie.

Better yet, there is also some music involved, and it is good to listen to, unlike sexism. The arrangements, all plaintively string-heavy with swingy guitar, doubled-up drum fills, punctuating cymbal crashes, and especially scaled-and-separated vocal harmonies, particularly wherever Gwenno Saunders’ gorgeous, rich Diana Ross throwback croon is featured (she boldly takes on the fills that Michael Jackson would have covered for the Jackson 5, Brian Wilson for the Beach Boys) all prime the audience for sweet+innocent let’s-get-married-in-the-chapel charming-but-retentive platitude of the doo-wop era. But forget that. The listener is quickly and cheekily jilted back to the future on almost every song. See “Dirty Mind” (Becki: “I feel positively pervy standing next to you / he’s got a dirty mind / just don’t know what you’re gonna find”) where our female protagonist is bored by her cute, OCD boyfriend until she discovers that he has “creative” ideas that would “make the devil scream.” Gwenno’s celebratory “ba ba ba ba’s” that support the chorus are normally heard on songs about “he loves me!” and prom-date wedding proposals. Here they congratulate the discovery of a sex-toy treasure trove. More power to the Pips, if it is indeed their power in the first place.

And that’s the last time that that kind of “but how feminist are they really” bullshit will be addressed in this review, promise, because, as suggested above, when you get into the record, it really means dick all, because, most penetratingly, the musical performances tower above any other aspect of the band’s work. See Gwenno’s rocketing chorus on “Your Kisses Are Wasted on Me,” or the way Becki’s sometimes-squeaky delivery injects extra doses of attitude. “Judy”’s bassline throbs and pulses and recalls Peggy March’s “I Will Follow Him,” while the song recounts a vaguely suggestive friendship between a high school misfit and a Pipette, climaxing in a handful of sputtering horns and swooning strings. And while every song contains allusions to forgotten surf rockish guitar chords and Duke Ellington violins, the real fun is in the way the Pipettes play off each other in harmony. At any stage in any song, there could be a back-up duet complementing the lead vocalist, one part of which will move to the forefront, and then all three voices will pile on top of each other, gleefully teasing the listener, coming and going according to whatever rhythm they’re subject to, but always working the melody until it’s spent, only to pick things right back up again before the listener is even ready, on the next song.

And there’s no better example of the harmonies than the final track, “I Love You.” It’s the only first-person romantic “love song” on the album, and it’s tactfully tracklisted after three not-so-lay-downers that are, in order, about 1) “Sex” (once again: “rest your pretty head…”), 2) a “One Night Stand” (“I left you alone, at four in the morning, not a stitch to wear…”), and 3) sexual frustration (“He knows all about the movements of the planets / but he don’t know how to move me” and, better yet, “He’s always got his head … in a book”). On “I Love You,” however, the Pipettes muster humility: “I’ve cooked you seven meals / six of them on which you’ve choked,” and, if you’ll double-take that line, actually play into the era-bound stereotypes that come with their sound. “I Love You” is not only an anomaly, but it’s actually a surprise, so convincing is the dogma of songs one through thirteen. Maybe that’s why it’s the shortest/last track on the record; but, regardless of the rush, the song is a subtly-complex multi-tracked soothsay, and the rare delicacy of the vocal performance underlines the sentiment.

And that’s the last time that I’ll address any bullshit references to feminist or sexism-related overtones on this album, because that stuff really means dick all when you just sit down, relax, and take the album in. It’s not like you can’t just accept it as it presents on its face, right? It’s not like you have to go any deeper, trying to hit some mysterious internalized “point” in order to figure some (mythical) concept of what’s really going on. Why should we presume that this stuff is all goal-oriented, anyway? We’re just asking to be caught with our pants down. Unless, you know, “Judy” is actually about lesbians. Then it’s so worth it, dudes. Sick.