Regina Spektor

Soviet Kitsch

(Shoplifting/Sire; 2003/2005)

By Christopher Alexander | 21 October 2007

This needs to be said, so I’m going to get it out of the way: what ungodly series of events led Regina Spektor to make a break-up record? Granted, I don’t know really know the person, so maybe she snores and is late with rent or robs fucking banks or something, and there’s evidence of a dipsomaniacal streak a mile wide. Tallying the math on my end, though, this should be a home run: a literate, idiosyncratic and gifted musician who writes funny, frank songs and whom, let’s be honest, is easy on the eyes. What hope do we mere mortals have if even she can’t keep it together?

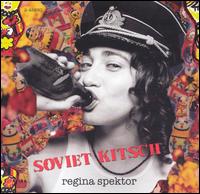

The sole clue lies in the booklet to Soviet Kitsch, Spektor’s major-label debut (and maybe the most peculiar disc to come out of RIAA-friendly territory this year). She looks at us from under the arm of a tattooed man, with a look on her face that isn’t exactly content. Nevertheless her arm clings to his, appearing eager to submerge herself into him. Cerebrally, I could say that this is indicative of a dysfunctional tendency to submit one’s own personality in love, of having one’s identity enmeshed with the other. Instinctually (and with record geek testosterone raging full bore), I say “Poor Little Rich Boy” was just too stupid to appreciate her, and Regina just doesn’t know that she could do so much better.

Lyrically, the former stipulation only comes up once, in the finale “Somedays.” “Some days aren’t yours at all / They come and go as if they’re someone else’s days / They come and leave you behind someone else’s eyes.” As for the latter, well, let’s start at the beginning, the appropriately mood-setting “Ode to Divorce.” “I need your money, it will help me/I need your car and I need your love/so won’t you help a brother out? Just break me to small parts.” Or the next one, the aforementioned “Poor Little Rich Boy:” “You don’t love your girlfriend/and you think that you should but she thinks that she’s fat but she isn’t but you don’t love her anyway.” We can keep going with the suicide fantasy of “Carbon Monoxide,” or in “The Flowers,” where she stays awake waiting for her lovers’ old flowers to bloom. I think it’s brilliant: Spektor excuses voluntary insomnia because “I’ll never know if I go to sleep,” but she winds up wasting her life anyway.

The party line on Spektor is that she resembles Cat Power and Fiona Apple, which is accurate enough, if a little lazy. Her husky vocal timbre recalls Apple at times, but she’s far more expressive, and utilizes a fairly dynamic range in the dramatic, if not the musical, sense of the word. She goes from a lower-register Joanna Newsom to a sweet coo on the stately waltz of “Carbon Monoxide,” and she’s playfully all over the map in “Your Honor,” a trash-punk ditty with Kill Kenada that makes Sonic Youth’s “Nic Fit” look like “Penny Lane.” The comparison loses water with Spektor’s classical training, though, which gives her piano playing and songwriting a bit of an edge. Check the intro to “Us,” an impressive run of thirty-second notes and odd accents that conjures visions of an alternate, okay-to-like version of “Angry Young Man.” Or “Flowers,” which ends with an Eastern European traditional.

There are two topical songs on Soviet Kitsch, and they’re conveniently packed together at the end of the album. “Ghost of Corporate Future” means well but falls flat, an allegory of a businessman who needs to stop and smell the roses because “people are just people like you/and the world is everlasting.” “Chemo Limo” is at least a hundred times more effective, a first person account of a woman with four kids whose insurance company won’t pay for her Chemotherapy treatments. “I ain’t gonna pay for this shit/I can afford chemo like I can afford a limo/and any given day I’d rather ride a limousine… besides, the shit is making me tired.” The song continues into a Dylanesque hallucinatory dream of the woman riding the limo with her kids, ending with an absolutely devastating description of her daughter: “Oh my God, Barbara, she looks so much like my mom.”

The moral of this story is that I don’t understand men, and I don’t understand major labels either. The same things that make her attractive as an (imaginary, fantastical and safe) mate to me typically spell commercial doom for the board over at Warner’s. It’s conceivable that she can be marketed as a hipper Michelle Branch (the string arrangements get a little schmaltzy), but at her most accessible she’s still too resolutely quirky, as on “Carbon Monoxide” which, to say nothing of its subject matter, makes a hook out of “wakka wakka wakka,” and then, “dead-uh dead-uh dead-uh.” Still, Soviet Kitsch is the kind of record I want to see major labels fund, market, and lose their shirts over, and I only hope they continue to give Spektor the chance.

The sole clue lies in the booklet to Soviet Kitsch, Spektor’s major-label debut (and maybe the most peculiar disc to come out of RIAA-friendly territory this year). She looks at us from under the arm of a tattooed man, with a look on her face that isn’t exactly content. Nevertheless her arm clings to his, appearing eager to submerge herself into him. Cerebrally, I could say that this is indicative of a dysfunctional tendency to submit one’s own personality in love, of having one’s identity enmeshed with the other. Instinctually (and with record geek testosterone raging full bore), I say “Poor Little Rich Boy” was just too stupid to appreciate her, and Regina just doesn’t know that she could do so much better.

Lyrically, the former stipulation only comes up once, in the finale “Somedays.” “Some days aren’t yours at all / They come and go as if they’re someone else’s days / They come and leave you behind someone else’s eyes.” As for the latter, well, let’s start at the beginning, the appropriately mood-setting “Ode to Divorce.” “I need your money, it will help me/I need your car and I need your love/so won’t you help a brother out? Just break me to small parts.” Or the next one, the aforementioned “Poor Little Rich Boy:” “You don’t love your girlfriend/and you think that you should but she thinks that she’s fat but she isn’t but you don’t love her anyway.” We can keep going with the suicide fantasy of “Carbon Monoxide,” or in “The Flowers,” where she stays awake waiting for her lovers’ old flowers to bloom. I think it’s brilliant: Spektor excuses voluntary insomnia because “I’ll never know if I go to sleep,” but she winds up wasting her life anyway.

The party line on Spektor is that she resembles Cat Power and Fiona Apple, which is accurate enough, if a little lazy. Her husky vocal timbre recalls Apple at times, but she’s far more expressive, and utilizes a fairly dynamic range in the dramatic, if not the musical, sense of the word. She goes from a lower-register Joanna Newsom to a sweet coo on the stately waltz of “Carbon Monoxide,” and she’s playfully all over the map in “Your Honor,” a trash-punk ditty with Kill Kenada that makes Sonic Youth’s “Nic Fit” look like “Penny Lane.” The comparison loses water with Spektor’s classical training, though, which gives her piano playing and songwriting a bit of an edge. Check the intro to “Us,” an impressive run of thirty-second notes and odd accents that conjures visions of an alternate, okay-to-like version of “Angry Young Man.” Or “Flowers,” which ends with an Eastern European traditional.

There are two topical songs on Soviet Kitsch, and they’re conveniently packed together at the end of the album. “Ghost of Corporate Future” means well but falls flat, an allegory of a businessman who needs to stop and smell the roses because “people are just people like you/and the world is everlasting.” “Chemo Limo” is at least a hundred times more effective, a first person account of a woman with four kids whose insurance company won’t pay for her Chemotherapy treatments. “I ain’t gonna pay for this shit/I can afford chemo like I can afford a limo/and any given day I’d rather ride a limousine… besides, the shit is making me tired.” The song continues into a Dylanesque hallucinatory dream of the woman riding the limo with her kids, ending with an absolutely devastating description of her daughter: “Oh my God, Barbara, she looks so much like my mom.”

The moral of this story is that I don’t understand men, and I don’t understand major labels either. The same things that make her attractive as an (imaginary, fantastical and safe) mate to me typically spell commercial doom for the board over at Warner’s. It’s conceivable that she can be marketed as a hipper Michelle Branch (the string arrangements get a little schmaltzy), but at her most accessible she’s still too resolutely quirky, as on “Carbon Monoxide” which, to say nothing of its subject matter, makes a hook out of “wakka wakka wakka,” and then, “dead-uh dead-uh dead-uh.” Still, Soviet Kitsch is the kind of record I want to see major labels fund, market, and lose their shirts over, and I only hope they continue to give Spektor the chance.