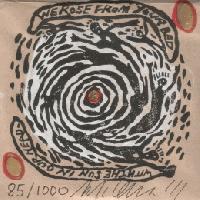

Swans

We Rose From Your Bed with the Sun in Our Head

(Young God; 2012)

By Conrad Amenta | 22 June 2012

In a recent discussion about this album, I made mention of Michael Gira’s once and now thankfully abandoned tendency to lock his audience in the building and turn off the air conditioning. This was done so that he may pummel them completely with a physical, exhausting experience. It’s the sort of anecdote we critics use to praise an artist’s unapologetic command of a performance space, be it Mogwai playing really loud or Tim Herrinton of Les Savy Fav singing into someone’s foot. I expected my friend to validate this assumption, but she said, simply, “Not cool. My body my choice, right?”

This surprised me at first. Isn’t living through a rare experience, especially a trying one, sort of a badge of honor? If we’re going to get into artist worship, isn’t subjugation to the individual the price you pay to experience his vision? I’ve thought of that conversation often as We Rose From Your Bed with the Sun in Our Head slowly devours my summer, annihilating every other piece of music on my radar until it sits alone, radiating in the darkness like Sauron’s eye. I think my friend’s comment helped me understand Swans better. I knew Gira was an uncompromising artist, but Swans is so clearly undemocratic, so unerring in the imposition on the listener’s headspace, that it may be unique. If the artistic principle can be mapped in degrees, then Swans is on the extreme totalitarian border.

I use that T word because the sound of Swans, and specifically this double live album—which arrives with all the weight of 2001’s monolith—is ultimately the end result of one man’s idealized space. It doesn’t describe an idealized world—Gira is far too critical for that—but exists because of a space without dialogue, without diversity, and without conciliation. It is the drone of an individual’s anger and frustration amplified beyond words. In it you hear not only the extant strains of Spiritualized and My Bloody Valentine, but the meta-gestures of the 20th Century’s extreme composers, Western minimalists, fathers of dissonance, and refugees from Great Wars: György Ligeti, Tony Conrad, Kryzsztof Penderecki, John Cage, Morton Feldman, Luigi Nono, Alban Berg. and Anton Webern. These artists sought to create music not only as a reaction to horrific events, but also to contradict and negate musical hegemony. They reacted to totalitarianism binarily, with totalitarianism in same, replacing one with another. When you are subject to the individual’s universal control, you experience a necessary loss of individual freedom. In a way, you see that which you used your freedom to feed, cast as evil in the artist’s view.

Gira clearly sees the world as a dead thing, corrupted by this essential contradiction. On “Eden Prison” he goes back to the site of man’s first expression of freedom, and when he sings “I am free” it sounds like an abhorrent birth. He even calls it “a stain.”

This music leaves little space for alternative views. Which is problematic as hell, because “My body, my choice,” right? At the center of Gira’s assumptions when he locks someone in a hot space and blasts them with noise is that the show is something they need to experience. It may not be pleasant, but you’re better off. So I’m torn between the perhaps coincidental fact that this album is succeeding in breaking down a few ossified listening patterns that I grow into every summer and the fundamentally terroristic nature of Gira’s musical project. Gira makes it difficult to mock Skrillex and drink beer in the sun; there is only Swans.

Importantly, this is removed from the conceptual confines of the “album”—which is to say a project that unfolds according to a predetermined narrative structure or at least in reaction to something. This artifact simply repeats what has come before, and so is meant to be experienced in the context of its smothering volume, its extremity, its dynamic fascism. Gira’s music doesn’t just sustain itself; it eradicates the possibility of other music. Listen to thirty minutes of this and then try to listen to, say, Beach House. That Beach House record is excellent, but “Other People” just doesn’t sound serious after the industrial crush of “Jim” followed by “Beautiful Child.” Extremism has a way of muting competing interests. There are no two points in this discussion.

Which is why I’ll concede right away that to experience Swans live one should probably be there in person, and in that this album can’t help but be a failure. You may come on passages throughout that transport you some distance towards the feeling of suffocation, the trivialization of melody and sentiment, but it can’t even be close to listening to two straight hours of this in an enclosed space. The music is heavy on 2010’s (still unbelievable) My Father Will Guide Me Up a Rope to the Sky, and it’s far from the band’s only live album, but it is an ideal entry point; the selection of songs here is almost less important than the deeply textured wash of immense sound. It is the best Swans live record in that it distills the essential loss of agency one is meant to endure as best as two little discs can manage.

Interestingly, too, Gira plays a few sketches of songs from the band’s upcoming album The Seer, which this live album literally serves as a fundraiser for the production of. It’s a fascinating concept, to hear a songwriter explain where he hopes the song will go, and then dabble preliminarily around the edges of it. We’re so accustomed to hearing only the finished product, I wish more bands would open up and make transparent their songwriting process in this way. Does it say something negative about music that the 58-year-old Michael Gira is still innovating in surprising ways while our young singer-songwriters predictably approximate their idols?

While listening to this album again, as I suppose I will do almost against my will for months to come, it occurs to me that Michael Gira has made a void of himself. He’s negated the concept of Gira as culturally significant, as industrial provocateur and spiritual nihilist. He has manifested as Swans in its most esoteric form: without referent, as a punishing/transcendent experience, to be surrendered to. As with Jason Pierce’s Spiritualized, it’s no surprise that the lyrics tend toward religious figures, notions of salvation, and, of course, loss and the void. This music seems to come wailing from an animal place: savage, disinterested, unforgiving. Michael Gira is the dictator made uncaring by the world he rules over.