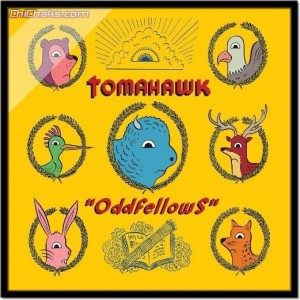

Tomahawk

Oddfellows

(Ipecac; 2013)

By Jonathan Wroble | 27 January 2013

Tomahawk’s third record Anonymous (2007), which threw the band’s frenzied math rock behind an actual Native American songbook (sample track title: “Antelope Ceremony”), was perhaps the weirdest thing yet in the Mike Patton oeuvre. For anyone acquainted with the kitschy horror metal of Fantômas, the FM-on-autoscan excess of Mr. Bungle, or the avant-garde applesauce of Patton’s solo efforts, the weight of that statement is clear. The man makes music that can’t be classified, music that raises the blood pressure as well as the eyebrows, music of such nonsensical machinery and madcap ideation that Patton being born in a town called Eureka seems appropriate. Since 1990, when he briefly flirted with the mainstream as frontman of Faith No More, the chanted lyric of their big hit “Epic”—“What…is…it?”—has become a reasonable listener reaction to everything he’s recorded.

These experiments often work—not always as album-length concepts, but certainly in little gasps. Anonymous for one was striking, edifying and rife with the awesome rhythms of John Stanier (Helmet, Battles). Tomahawk’s prior records, their self-titled debut (2001) and Mit Gas (2003), were arguably excellent, each a taut collection of nightmarish accents atop the undeniable melodies and movements scripted by guitarist and songwriter Duane Denison (Jesus Lizard). These efforts were strange but sensible, a workable weird; they were unfamiliar but from a safe distance approachable, and at all edges showcasing the manic talents of the band members. Now comes Oddfellows, already earning industry euphemisms like “back to basics” and “stripped down.” But here’s what that really means to those who’ve championed Tomahawk for its quirks: this new record is thin on ideas, lacking in offbeat ingenuity, and, most disappointingly, haplessly regular.

Part of this normalcy is by design, specifically envisioned by Denison. He told SPIN that Oddfellows is “meant to be played in huge clubs with alcohol and drugs and dancing girls,” a raison d’être entirely incompatible with his band, at least creatively. First single “Stone Letter” is a primo culprit: it sounds downright radio-ready, a pop/punk chug with predicable dynamics and a set of lyrics—“I wrote it, you got it / Don’t deny you thought about it / You don’t know me anymore!”—that Taylor Swift might have discarded for their heavy-handedness. The title track, which sounds like Jon Spencer fronting Tool, toys with a 7/4 time signature to seem challenging, but the trick limits more than empowers the band. Stanier is kept to timekeeping, Patton mostly grunts, and Denison’s Van Halen noodling seems tacked on at the end. It’s meant as a mission statement, and, as a falsely ambitious song leading a largely sterile album, it sort of is.

Granted, it’s almost reflexive to be extra hard on a band with such innovative history. Five songs on this album—an unbroken stretch, in fact, from “Rise Up Dirty Waters” through “Choke Neck”—stand shoulder-to-shoulder with anything Tomahawk has done, even establish a watermark for possibilities to come. “Rise Up” blends jazzy prog with aggro rock, a particular feat for Stanier, while on “I Can Almost See Them,” which repurposes the “Immigrant Song” howl as a shootout whistle, he thankfully reassumes his tribal drumming. “Choke Neck” swings into the album’s most dinosaur riff, “The Quiet Few” cleverly reuses the bending guitars of Pink Floyd’s “Learning to Fly,” and set highlight “South Paw” has new wave verses and an absolute assault of a chorus. It also features Patton’s most bizarre imagery: first he tells his subject that she’s “got some shit hanging off [her] lip,” next screams at her to put her clothes on. Elsewhere, when the arrangements are less imaginative, his trademark lyricism—at best oddball, at worst touchy uncle—comes off like some bad prank.

Still, even with a hot streak in place, this album is far too domesticated to flex the Tomahawk name. Even its best songs are short—the lengthiest here is four minutes, most clock in under three—and therefore feel cut at the knees before they can grow into mini-opuses. As it is, Oddfellows is the aural equivalent of finding out your freakiest old college buddy, the one who thieved panties and set the animals in the bio lab free, just got engaged. The fragments and instincts of a weirder, better Tomahawk are here, as is the band’s winning dynamic—its give and take between Denison’s straightforward songcraft and Patton’s alien leanings, any friction masked by Stanier’s thundering percussion—but everything is buried in dull production and bids toward mass appeal. It’s the sound of all the band’s weapons unceremoniously blunted.