Vampire Weekend

Modern Vampires of the City

(XL; 2013)

By Andrew Hall | 29 May 2013

Sometimes strange things happen and bands once easily written off go and do something completely unexpected, like making a record so good that it forces the listener to reconsider most of their preconceived notions and hang-ups about that band and their audience. Sometimes that listener is me and the band is Vampire Weekend and the record is Modern Vampires of the City, and this combination throws me into crisis mode.

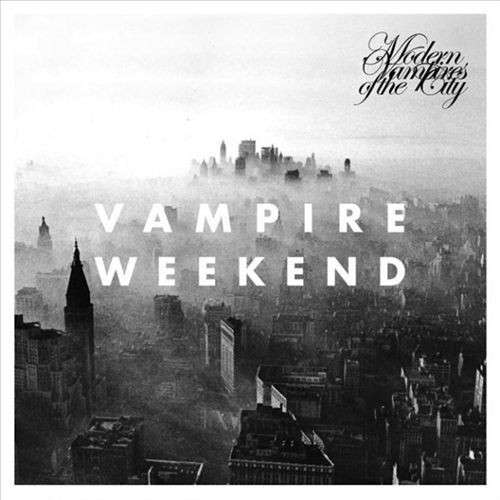

Like most of the Glow’s staff, this hasn’t been a band I’ve been particularly fond of. Their self-titled debut (2008) still sounds cloying, overwritten, and overstuffed. It still reminds me of getting trampled by drunk dudes while they played a pretty uninteresting set at a summer festival in 2008, and of really earnest conversations about “Oxford Comma” and Oxford commas, none of which I’m especially fond of reliving. Contra (2010), its followup, fares better, in that it had one knockout single, “Giving Up the Gun,” and in how frontman Ezra Koenig used his songs, rather than outraged and overwrought Tumblr posts, to dissect almost all of the class criticism leveled at his band over the course of their mainstream ascendance without ever making explicit that he was doing so. But the growth from that album to Modern Vampires of the City, its title excepted, is staggering. On this record, Vampire Weekend ditch the bulk of their first two albums’ influences in favor of a palate as comparatively stark and monochrome as its cover. Meanwhile, Koenig, always a precious observer, becomes someone capable of communicating genuine empathy and honest, real anxiety on two of the Big Topics viable in big, relatable pop music: mortality and breakups.

Producer Ariel Rechtshaid deserves at least some credit for this. Unlike Vampire Weekend and Contra, both of which were produced by keyboardist/arranger/aesthetic director Rostam Batmanglij, Modern Vampires of the City’s songs rarely feel overstuffed or overwritten, with simple kick-snare drumming, plaintive piano chords, and astoundingly well-recorded vocals at their centers. The surrounding ornaments don’t sound like they’re chasing trends for the sake of gimmickry—the autotune of “California English” has not given way to any Skrillex-esque wobble this time out—and what vocal manipulation there is serves pop hooks. If they are aping anyone this time out, it’s minimal, melancholic producers like Noah “40” Shebib and others who had worked with Rechtshaid in the last several years, like Sky Ferreira and Cass McCombs, who also benefited from the producer’s ability to rein in bombast and draw out subtlety in unsubtle songs. When they do cacophony, as they do on “Diane Young” (conveniently both a homophone for “dying young” and a New York City anti-aging spa), it’s less Paul Simon and more Tusk (1979)-era Lindsey Buckingham, a welcome change for a band that seemed fated to exist perpetually in a circle of early twenties know-it-alldom no matter how old its players got.

Stunning first single “Step” makes evident the band’s growth, however, within a matter of minutes. While the song quotes Souls of Mischief’s “Step to My Girl” musically and lyrically, and begins on a typical verbose Koenig verse seemingly bogged down with references and credibility checks—his tapes come “from L.A., slash San Francisco, but actually Oakland” because Souls of Mischief are Oaklanders, sure, but it rings all the more relevant if you’ve spoken to almost any band supposedly from San Francisco in 2013 about where in the Bay Area they live—he ends it at “girl that was back then,” moving on to a chorus that acknowledges the existence of both Jandek and Modest Mouse in one couplet. Over the next two verses, his language gets simpler and more direct until it reveals itself as a pretty straightforward breakup song, and a pretty good one at that. “I can’t do it alone” at the end of the chorus trumps the preceding nonsense, and all of a sudden the harpsichord in the song’s intro feels less like the dressing around the opening credits of a Wes Anderson movie and more like the emotional gutpunches Anderson can pull when he’s at his best, no matter how ridiculous his worlds and his characters are.

It’s these breakup songs where Vampire Weekend demonstrate their growth most astoundingly. “Hannah Hunt” sounds like nothing else in the band’s catalog, drifting quietly and plaintively like the road trip Koenig’s lyrics narrate, until the moment in which everything for its narrator snaps a little over two-and-a-half minutes in. A snare hit and a piano solo burst out of nowhere as Koenig screams, in a howl that sounds worlds removed from any Vampire Weekend song, what effectively serves as the song’s chorus: “Dammit, Hannah, if I can’t trust you / There’s no future, there’s no answer / Though we live on the US dollar / You and me, we got our own sense of time.” It’s a stunning, go-for-broke moment, the kind I never thought this band capable of.

Mortality, death, and time all linger here: “There’s a headstone right in front of you / And everyone I know,” Koenig sings in the chorus of “Don’t Lie,” while “Wisdom’s a gift but you’d trade it for youth” rings like a thesis statement for the whole record when it opens “Step”‘s third verse. But it’s Koenig’s unrelenting optimism on Modern Vampires of the City—even as he dissects unrelentingly heavy things, building to a full-on challenge to the existence of any supreme being on “Ya Hey”—that makes Vampire Weekend so effective at this stuff, so capable of turning potential exhausting singer-songwriter fare into great pop music. Unlike his peers, Koenig’s predisposition for sunny melodies makes the moments of darkness all the more affecting, less rooted in aw-shucks philosophizing and more in knowing that things are sometimes, if not often, vast and unknowable and painful and terrible, but it’s possible to not be consumed whole by that vastness.