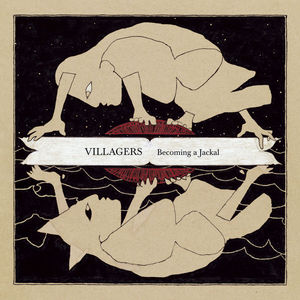

Villagers

Becoming a Jackal

(Domino; 2010)

By Conrad Amenta | 18 June 2010

Becoming a Jackal, written and performed entirely by Irish singer-songwriter Conor O’Brien, is the stuff of a modernist’s pure and beseeching naiveté. A confessional and a cross, it contains youth as animalism personified, aging as metamorphosis, alienation from authority figures in their hoary, stone-faced institutions, plenty of talk of “The Dream” in its nebulous permutations, and the dead invested with some great perspective. In other words, Villagers is reinvested in the project of cause-and-effect, refreshingly uncynical and unironic and linearly mortal at a time when our talk is about whether there’s any difference between M.I.A.’s refugee-chic symbol appropriation and Lady Gaga’s nonsensical if visually arresting jabbering.

So O’Brien risks all of the easy pokes suffered by his stylistic progenitors, those poets who waxed egotistical and whose worldview seemed alley-trim, at least to those of us who watch simulcasts of earthquakes, oil spills, and political upheaval in distant places. It seems almost quaint, now, to hear “I was a dreamer / Staring out windows / Out onto the main street / ‘Cause that’s where the dream goes” and to appreciate “Becoming a Jackal” for its poignant, composed self-caricature, its chimney sweep romanticism. The song moves intuitively through its push-pull perceptions of caretaker/jail keeper, thematically melodramatic even as it’s aesthetically tidy. The home and the street become broad brush narrative elements, and O’Brien’s protagonist is as repulsed as he is attracted to the promises made by the jackals outside.

The album’s crux can be captured in the dynamic between “Ship of Promises”—another classic transformation narrative about physical distance and enchanted spaces—and “Home,” in which the titular sphere becomes a twisted and apocalyptic space. On the former O’Brien sings: “You see a mask from your window at night / So you wake and you go outside / And you put it on / And they treat you in a different way / But you can’t understand what they say / After you put it on,” and in these plaintive lines he captures the simplicity and urgency of the album’s metaphors: sudden and unalterable transmutation is followed by flight, an inevitable incompatibility with home. On “Home,” where the narrator tries to return from his ship of promises (where, it should be noted, he “just could not care less” anymore), those former comforts become part of a cathartic sacrifice. As the toms merrily bounce along and a folksy, small piano line plinks downward, O’Brien sings on a minimalist diddy: “The mother prepares the weapon / Before handing it to son / Who watches as daddy runs.” And then, sparer still, “The flames wander through the city / And set fire to the sea / And out of the blaze appears a face.” The narrator of Becoming a Jackal submits to his basest instincts in a bid for self-reliance, sees himself transformed and recognizes, unapologetically, what he’s become. Fair to say that we’re beyond this kind of linearity, well into ironic appropriation and deconstruction and hybridism, but it’s hard to deny the efficacy of O’Brien’s delivery, the tunefulness of his poetry.

The problem, such as it is, is that O’Brien’s targets are as obvious as those old modernists’, whose warning about dehumanization and the powers that be are met with a resounding “well, yeah” by a generation for whom Vietnam isn’t a source of alienation but an historical footnote. What’s an album that targets the church as non-transformative and routine, just “checking in at the sound of the bell,” to those of us who see the extent of the church’s utterly despicable practices? What is targeting the state for those of us for whom Iraq has become a Zen state of never ending war? Becoming a Jackal may be a modern album, but it certainly isn’t current.

The occasional Conor Oberst comparisons aren’t wholly inappropriate, O’Brien conjuring world-weary traditionalism in at least equal amounts to Oberst’s forced Americana. But there’s a tendency to view this kind of music from outside the thing, to view traditionalism as an exercise that can no longer be genuine so much as genre exercise. The intuitively penned vocals and backups, the immaculate production, the uncomplicated, unpretentious instrumentation: it’s miraculous that a morality tale like this, even with the occasional intercession of brass or strings, can come across as sincerely as a person simply offering his reflection on the crucible experience of attaining adulthood. In other words, Becoming a Jackal is downright convincing—maybe sustaining—even these few weeks after first hearing the thing. I’m surprised, though maybe I shouldn’t be, by just how cool and atypical that feeling is.