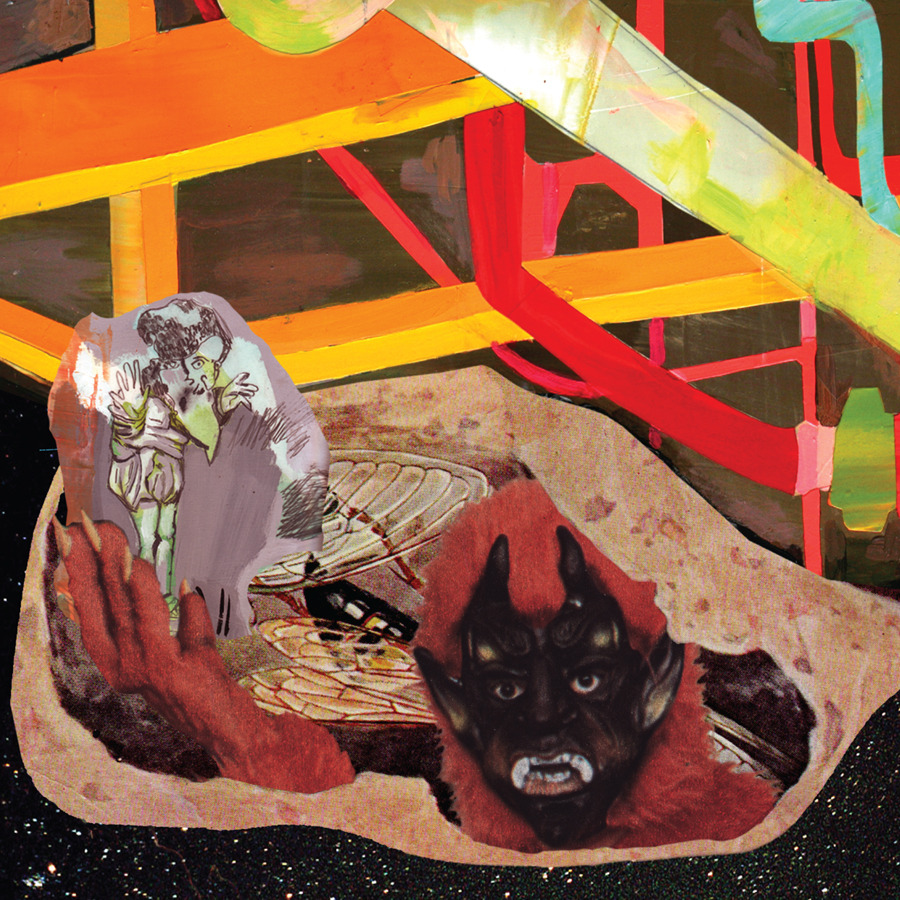

Wolf Parade

At Mount Zoomer

(Sub Pop; 2008)

By Mark Abraham | 17 June 2008

Let’s bang humanity’s drum by looking at the most recent issue of In Style. The always-on-the-pulse feature editors have asked a bunch of celebrities what the most sexy things are. As always with such quizzes, potential answers are introduced as either/ors: culture or In Style or the editing process has locked these stars into picking from a list of already sanctioned-as-sexy things. Thus, sexiest clothing: nothing but heels. Sexiest calendar: nothing but firemen. Sexiest music? If you guessed Marvin Gaye: right! If you guessed Barry White? Surprisingly, no, but whatev. Gaye and White get enough exposure as the coffee/tea divide of morning talk show sexuality; straight and black is the most sexual (through our culture’s curious stranglehold on “true” things from like 1877), both a celebration and the ugliest stereotypes of our history held up in outstretched, cupped hands. So what I learned from the article is that a) old is the new new so b) therefore, black men make real sexy music for knocking boots and that c) consequently, what everybody wants is to see Eva Longoria-Parker dancing only in heels on a fire pole to “Sexual Healing.” Hell, the magazine even tries to cut the middleman out of our presumed shared fantasy, even though there’s no music, no fire pole, and Longoria-Parker is actually dressed in the picture. The entire fantasy is reduced to a red arrow pointing at her shoes. And the earth collectively orgasms. Or at least the foot fetishists do.

…well, I mean, they don’t really, at least by In Style’s standards, since apparently the vast multitude of human desires can be expressed through multiple choice. But this is the cultural stagnation Wolf Parade has always wanted to escape, right? This is why Spencer Krug (still) presents horses and horse riders and other animals as the building blocks of our cultural erection, teasing homoerotic fantasy as suture for the constricting heteronormative imperatives of commercial and consumer sexuality. Plus, he discovers himself, often painfully, in his out-of-city therapeutic fantasies. Boeckner is also riding horses this time, screaming, “and what you know can only mean one thing,” or “they still don’t mean a thing,” or, rephrasing himself, “it don’t mean a thing.” That’s the crux of Wolf Parade’s assault on the modern condition: no matter how active you are on the fringes, your activities get filtered through successive levels of hierarchy until they become either/ors. Get out of the suburbs, get out of gossip rags, “let the needle on the compass swing,” get away from appliances, those “100,000 sad inventions.”

“Get to where?” is the question, and if Boeckner chronicles the decline of modern society because he knows everyone and their respective knowledge and experience is “rooted to the place that you spring from,” Krug always seems to be out in the wilderness searching for isolated springs to call home. And even if Boeckner slips occasionally into outdated retaliations against 1950s domesticity/white flight/suburban whatevers, or if Krug could have the most awesome (and sexiest) zoo in the world if he collected the fantastic creatures littered across his Wolf Parade and Sunset Rubdown imaginings, Wolf Parade the band, in unison voice, still manages to say “the modern world sucks in general, so find hope in the specifics” better than anyone. And so Krug’s in the forest and Boeckner’s in the urban core, and they reach across the suburbs at one another to hug the hurt from the world.

Of course, if Wolf Parade want to fuss with dominant mentalities, their efforts are at the mercy of the epic frivolity of indie-fandom, because let’s face it: we’re no better than In Style half the time. When Apologies to the Queen Mary dropped in 2005, it did so late in a year full of half-cocked victories and against the first real tidal wave of blog hype. It seemed like a cataclysm of rock tropes forced through the sieve of the band’s—and especially Krug’s—peculiar mentality. It was exciting enough that the album’s midway-lull was ignored. Okay: I’m not backhandedly shitting on Apologies to the Queen Mary, to be clear. I’m just pointing out that the hype surrounding it meant that liking its sexy indie heels meant something. Which makes sense, since indie culture isn’t a rejection of commercial culture; it’s a modification, right? We’re so hard-wired as humans to define ourselves through the shit we buy (or own)—Boeckner’s “100,000 sad inventions”—that we produce alternative consumer cultures where the objects we own mean what we want ourselves to mean and then we turn around and say we live a different way than our parents. It’s true and it’s not true, and I think Wolf Parade’s politics and aesthetic are, consciously or unconsciously, mitigated by that fact. Especially given that Boeckner and Krug may be saying the same things but coming at them from different angles, making subcategories of Wolf Parade identification strategies: Krug-fans and Boeckner-fans.

At Mount Zoomer may mean we have to lighten up a little: Wolf Parade is not going to save the world, and they may not even save rock ‘n’ roll, but they can show us alternative visions of what rock could be. In that sense, Wolf Parade’s sophomore slump manifests itself entirely in their stupid choice for their new album’s title; otherwise, At Mount Zoomer is a tremendous success, even as the Sub Pop promo department is throwing around The Lamb Lies Down on Broadway (1974) and Marquee Moon (1977) as catch-alls for what it means to rock today. Old is the still new sexy; reissues are the new hype; punk is better than prog—“so don’t front, prog geeks, ‘cause we don’t want you,” they mean; rock operas are fashionable again; Krug screams “fire in the hole.”

I’m a prog geek, at least in part, and I’m telling you: this album is less and more important than that, because it still means liking Wolf Parade means something even as it interrogates what that something is and makes it harder to choose between Krug and Boeckner (not for lack of trying) as ways to situate yourself within a selective interpretation of what the band does or is. Hell, At Mount Zoomer might even be contentious! Or maybe it isn’t, probably, since 2008 seems to think that out is the new in as long as it isn’t too out. And that’s the main reason the Sub Pop one-sheet’s comparisons work: The Lamb Lies Down on Broadway saw Genesis reeling in all of their prog fetishes, internalizing them within pop songs; Marquee Moon saw Television transforming proto-punk into prog. In Sub Pop’s estimation, then, At Mount Zoomer is like, say, condensing the entire riffage of King Crimson into a 2×2 Bento Box and icing it with the best riff in the world ever—yes, I’m talking about the hook of Mariah Carey’s “Always Be My Baby”—and then having the Buzzcocks record it in a basement somewhere. It’s a cubist approach to music, as opposed to the surrealist rendition; everything fits against everything else comfortably, rather than everything always trying to escape. And I’ll cop: it’s actually easy to hear the fractured strains of “Back in N.Y.C.” in the keyboard riffs that drive Boeckner’s “Soldier’s Grin,” easy to hear Gabriel-ian theatrics in Krug’s every yelp, easy to hear Verlaine-ian technique in the guitar solo on “Fine Young Cannibals.” But Wolf Parade aren’t drawing in so much as filling up. If, as is the typical perception, their music used to play urbanism (Boeckner) and anti-modernism (Krug) against one another, I think they’re starting to see the relationship between the two and, consequently, to capture a whole mess of details inside the structure of their aesthetic, making this album more cerebral than the immediately ragged Apologies to the Queen Mary.

In part, complicating the either/or of Boeckner/Krug is due to the rest of the band seeming more present here. Arlen Thompson’s drums are more integrated into the dynamic range of the songs, Hadji Bakara’s sound manipulations are even more subtle and more crucial than before, and Dante DeCaro’s additional guitar work gives added range to the band’s sound. But the easiest way to note the difference is how each album starts: if “You are a Runner and I Am My Father’s Son” shelters Krug’s fantasies of emotional detachment (I love how he revels in emotional pain) inside a stark drum/keyboard duet that screams, “RAWK,” Boeckner’s “Soldier’s Grin” begins with a hilarious synth riff that undermines, however briefly, any expectations you had for what At Mount Zoomer should sound like, or at least what Boeckner songs should sound like. And, indeed, among the Boeckner-fans cries of “too much Krug Korg” is the main complaint around the office. Funny, since the Krug-fans seem concerned with a lack of Krug. I’m in the middle, happy to see a closer union of the two styles manifesting itself in a complication of the band’s overall sound. In fact, I like At Mount Zoomer more than the band’s debut, even if many of my colleagues—at least according to their ratings—don’t. And yes, that means I would have been on the low (but certainly not the Alexander low) end of the Queen Mary indie-crush spectrum.

It was initially surprisingly to me, since I like craziness, that my favorite thing about At Mount Zoomer is how Boeckner’s grown as a writer. In hindsight, though, this probably was inevitably his album to grow, as it’s becoming increasingly clear that Krug’s Sunset Rubdown side project isn’t an outlet for non-Wolf Parade material so much as a venue for his prolific creativity. But even if 2005 Krug-style gems like “Grounds for Divorce” or “You Are a Runner and I Am My Father’s Son”—songs that splayed and reorganized the corpse of pop music on an operating table—are a thing of the past, Wolf Parade’s version of 2008 Krug is enticing for entirely differently reasons. “Bang Your Drum” is a good example: the surrealist approach he takes with Sunset Rubdown is reigned in, and so elliptical verse structures run in place before crashing into elliptical choruses that run at full tilt before Krug grabs the mic and leads his non-existent audience in a rousing chorus of incredibly meaningful singsong non-words.

Krug and Boeckner share cerebral concerns: you reach the edge, you could “take a dive,” but “how can you turn away?” If I were reaching, I’d say Krug’s increasing refusal to write outside of the niche he created for himself is itself a rejection of the indie music he’s supposed to produce: he’s less a musician now than he is a personality, alternately directing his audience and splashing his fantastical whatevers on the ground in front of them. Maybe he’s berating himself for lauding life in the wilderness while living in Montreal, though his few tales of the city are equally self-denigrating, as “California Dreamer” shows. Either way, Krug’s Sisyphean chord progressions usher in inspired and related musical work from the band: the end of the song is a miasma of noises working at counter-purpose. The brilliance of this and many moments like this on At Mount Zoomer is that the band manage to build hectic and moving moments out of calculated chaos. Check “An Animal in Your Care,” where a threaded and subtle guitar riff that sighs in the background of the initial parts of the track suddenly becomes an epic, thundering outro.

Point being, even if Krug’s gotten more internal, looping about himself in the most fascinating ways, it’s the band+Boeckner that keeps him grounded, just as the band+Krug leavens Boeckner’s compositions, uniting his straightforward delivery with the eclectic approach the band increasingly excels at. Even “Grey Estates,” At Mount Zoomer’s closest equivalent to “Modern World” or “Shine a Light,” is a bustling mini-prog/surf workout. It’s the band’s finest pop single to date, I’d say, and it’s actually kind of funny: despite how complex it is, if you compare it to “Shine a Light” or “Modern World”—songs that have a similar feel—the old tracks are much slower. Every odd keyboard riff and noise that appears here seems to be calculated into the structure of the track; every shift impacts the meaning of the song. Boeckner’s best when he’s at his sharpest, but the band’s ability to complicate that sharpness here, on “Language City” and on “Soldier’s Grin,” is fascinating; his rock songs cloaked in carnival clothing, they move like the zombies in the video for “Thriller,” or at least the ones Krug digs up in “An Animal in Your Care.” Pop songs.

Even “Kissing the Beehive,” a gasping outro that sort of takes the idea of a Boeckner/Krug duet to its illogical extreme, works perfectly with its Spector-drum riff, spiralling guitar squalls, and kind-of-funny backing vocals. And that vaguely cinematic riff that rolls over the middle cinches the whole melodrama of the piece together in a way that screams “seriously” and “don’t take it so seriously” in the same breath. Either/or, right? Except “Kissing the Beehive” makes it hard to know where one starts and the other begins, and Wolf Parade in general are making it increasingly hard to talk about this band like it’s urban/rural, modern/anti-modern, or Boeckner/Krug. In retrospect the album title almost makes sense: Wolf Parade express a longing for a fantasy world that maybe only they still dream of, one they can only grasp through the release of making music, and so in name At Mount Zoomer declares, “Here we are, standing on our peak, happy in this moment, at the studio that our drummer made with his own two hands.” Whether you like it more or less than their debut, this album means that in 2008 this band lives on despite their hype and despite the way they’ve been constructed in indie fandom. They’re just Wolf Parade, fucking shit up for breakfast.