Features | Lists

By The Staff

50 :: Black Dice

Beaches & Canyons

(DFA/Fat Cat; 2002)

When I went to see Black Dice open for Godspeed You! Black Emperor at Toronto’s Palais Royale shortly after Beaches & Canyons dropped, I was afraid for my life. Having only heard my roommate’s early 7’‘s, and being regaled with stories of trashed equipment and beatings of other band- mates/audience members, I stood somewhere way in the back of the club where I had to squint to see a group of guys huddled over knobs and moaning into mics. Granted, nothing really matches the feeling you get when you think these ominous-sounding industrial bleeps could explode at any minute—something like when you mix a bunch of household chemicals and ingredients together in the bathtub as a kid—but the aftershock of the band’s delinquent past still resonates through this album.

And now Beaches & Canyons itself has become something in the distant past. It might seem normal now, but at the beginning of the decade noise (Wolf Eyes) wasn’t the same as noise (Excepter), and Black Dice were clearly way out of their element. Especially considering the string of inferior successors where the band seems to be trying too hard to refine their sound or force the weirdness, it’s still revelatory how accidentally brilliant it all sounds. Its transcendent moments are hardly superficial or tongue-in-cheek—whatever that woodwind is at the beginning of “Endless Happiness” its really on some Buddhist-master-on-a-mountain-top trip, and even those erratic sparks of static that open “Things’ll Never Be the Same” make beautiful use of space, at least until the band cuts up the silence with power tools. This album is just as much about dismantling beauty or stumbling upon it in unlikely places: opener “Seabird” sounds vaguely like someone revving a motorcycle at sunset, and is both as sincere and obnoxious as that suggests. Then there’s the six minutes of ocean sounds which close out “Endless Happiness,” like a mock album-outro before the sixteen minute percussion jam of “Big Drop,” well, drops. If that’s not punk rock I don’t know what is.

Joel Elliott

49 :: Ellen Allien

Berlinette

(BPitch Control; 2003)

Full disclosure: though I am currently writing the blurb for our site’s number one album of the 2000s, Berlinette is my personal favorite album of the decade. And part of that’s instinctual; I’m not sure I have any broad, epic language to explain why, since the most powerful, fun thing about this album is just listening to it, and hearing how brilliant Allien’s approach to music is. The opening moments of Berlinette lay out the aesthetic brunt of the whole album: “Alles Sehen” drives that tinkertoy drum intro into your brain before smoothing out into something far more epic. And that divisiveness is apparent throughout: harsh and soft; angular and smooth; the kind-of-measly versus the epically lush. It’s a tension Allien deploys to great effect throughout the album; the gorgeous “Sehnsucht,” for example, works because of the way she undercuts more traditional dance sounds—which, in their traditional contexts, would be meant far more seriously—with those brilliant sliced up samples of her voice. And that’s why I love Allien’s work so, so much: her effortless ability to explore sometimes severely experimental ideas inside a shell of accessibility. A candy shell, maybe. A coating. A…well, I won’t follow that metaphor to the point where it becomes product placement for her clothing line.

Berlinette sounds like it was made on the dance floor for a grimy basement noise show. Like, you can imagine dancing to this stuff (though I’m not sure you’d be successful if you tried), but there’s a whole lot to be said for this being one of the better out albums of the decade. Just listen to the metal fantasies of “Trash Scapes,” where a faux-guitar route is sculpted through calculated pitch bends into the most memorable part of the track. Turning weirdness into hooks is a skill many do not possess, which is why I mentioned Allien and Animal Collective in the same breath in my review of her even more experimental Sool (2008): across that divide, Allien often seems to fit as naturally with the freaks and weirdos who push the developmental side of indie culture forward as she does with the club goers and fashion icons of the techno scene in Berlin. And on top of all of that there’s a political subtext to her music: from the title, which suggests this is one woman’s view of her city, to the song titles, which both celebrate and criticize that geographic space, Berlinette is ultimately an album that relies on Allien’s brilliant merger of pop and experimental approaches to techno music to show all the sides—good and bad—of a city, of art, and of life.

Mark Abraham

48 :: Sleater-Kinney

One Beat

(Kill Rock Stars; 2002)

Whole album leaks were still a relatively rare entity back in 2002—and so, on that sunny Saturday afternoon after I purchased Sleater-Kinney’s One Beat from Hamden, Connecticut’s dearly departed Exile on Main Street, now behind the wheel of mom’s Toyota SUV, the conclusion of the record’s opening title track found me going 70 in a 45. Upon hearing the bridge of “Far Away” for the very first time, I nearly drove off the fucking road. True confessional: Sleater-Kinney almost killed me.

“Far Away” is One Beat‘s finest, but it also has the arguable distinction of being the band’s most important song. Not only does it serve to mark a transition point in the band’s ever evolving sound, its lurching Sabbath riff the missing link between All Hands on the Bad One‘s (2000) relative whimsy and the psych-rock bulldoze of 2005’s awe-inspiring swan song The Woods, it’s also a poignant, frightening take on the 9/11 catastrophe, through both the prism of Corin Tucker’s burning need to shelter her newborn son and that of a helpless populace scared shitless while “the president hides / and working men rush in / and give their lives.” My wife arguably likes Sleater-Kinney more than I do, but even she can barely listen to “Far Away” on account of how queasy it makes her feel. Of course, it rocks like a hell beast; Janet Weiss’s snare abuse at the bridge is possibly the hardest any single person has ever whacked a drum in the history of percussion.

Not every track on One Beat is as palpable in its unrest as “Far Away,” but the band has clearly stated in interviews that One Beat was designed to be their “political” album, with the issues of feminism and self-identity previously explored on Bad One and to a lesser extent Dig Me Out (1997) largely taking a backseat to the headlines. Take “Combat Rock,” an overt protest song employing a skittering riff and explosive chorus to tackle the Bush administration’s “either you’re with us, or against us” mantra. Likewise, Motown-inflected burner “Step Aside” mutilates “Tears of a Clown” to suggest that the best antidote to the wartime blahs is the dancefloor. Corin Tucker and Carrie Brownstein consistently produce the most acrobatic overlapping punk riffs this side of MacKaye and Picciotto, and Janet Weiss does nothing to alter her earned status as “Bonham with bangs,” particularly evident on the Physical Graffiti (1975) stomp of PDX-tribute “Light Rail Coyote.” The Woods may be the band’s most ungainly record, one that could easily obliterate every wall of rock within a ten year blast radius, but One Beat is amazing for both its heft and the forcefulness of its ideas, Sleater-Kinney at their locked-in, SUV-totaling best.

David M. Goldstein

47 :: Gas

Pop

(Mille Plateaux; 2000)

Drone ambient is not a genre that gives easily to rankings, and never less so than on a Top 100 list of an entire decade. Calum put it better than I can when he questioned whether “producing pleasant soundscapes simply precludes producing duds” and suggested that perhaps drone ambient needs “Aboutness” to truly resonate. Pop is not merely “pleasant,” its soundscapes are utterly sublime: in their calm, their totality, their organic pulse. But still, it’s a nearly insurmountable task to examine the composition of these untitled pieces to figure out what Wolfgang Voigt imparted onto them to make Pop one of the stand-out ambient records of a decade filled with similarly beatless pinnacles. We can’t exactly surmise that Voigt’s album is about something in the way, say, The Disintegration Loops (2002-2003) is: it has no obvious concept that immediately elevates its tranquil beauty above ear candy and into profundity.

Perhaps Pop, as the case may be, is simply the one excellent ambient album that more of us encountered and thus loved than any other. If that’s so, if Pop has to fly the flag for a hundred other albums, it’s a worthy standard bearer: though much is made of the mechanical/human dichotomy in electronic music, Pop blurs to almost unprecedented levels the point of contact between the natural and the synthetic. Are those flowing water sounds and insect chirps field samples taken from a forest or studio recreations? Are those heady timbres orchestral in origin or borne entirely of a machine? Does this album capture in microcosmic, fractal beauty the world around us or does it create a tiny reality of its own, a simulacrum space we can visit for 65 minutes but never occupy permanently? While savoring those questions, knowing that Pop may not be about anything much seems to matter little.

Jack Moss

46 :: Black Milk

Tronic

(Fat Beats; 2008)

Rap’s uniqueness as a genre emanates in principal from its sport-like structure which facilitates—or nearly necessitates—competition amongst its practitioners. The genre operates like a small high school, made smaller still by the omnipresent tentacles of the internet, where everyone is up in everyone else’s shit. All the time. You hear Lil Wayne got caught with a .40 cal in his locker? Did you know Jay didn’t visit Beanie in juvie even once last year? I think I saw Kanye trying to kiss Drake last weekend… Something like that, but with music, too. There are exceptions, or course: artists who have carved out a niche in which they operate comfortably, distanced from all the calamitous conversation—Madlib seems content to roll spliffs and chop jazz loops in his basement without a care in the world—but as we’ve learned from decades of well-documented disputes, combativeness pervades hip-hop, each sonorous beat or blistering verse serving implicitly (sometimes explicitly) as a challenge to the rest of the community.

Black Milk doesn’t just understand this virtue, it swims in his cells. It’s like, if we follow my teenage analogy, he is the younger kin of a legend (Dilla), his shine obscured by the elephantine shadow of his spiritual antecedent. Thus, Tronic is Milk’s attempt at strong-arming his way to individualistic notoriety, utilizing his considerable DNA to become the most renowned dope slanger at Carlton Ridenhour High. Or whatever. The point is Black Milk’s sophomore effort is vastly superior to his debut, vastly superior to most rap records. It’s a testament to the sheer force of will—BM doesn’t bother winning your respect, he takes it by force—just as it is also a testament to the way beats and bars congeal: a dense, smoldering mass of science directly resulting from Black Milk’s fastidiousness. One imagines BM hunkered over a soundboard in some smoky Detroit studio, tweaking the reverb on his drums so they knock with the most precise obstinacy; if his rhymes are to be believed, this meticulousness stems from his frustration that other artists can’t get on his fucking level.

So Tronic is an Accomplishment, a satisfying culmination of potential and assiduousness that resounds with Biblical force. If guest rappers Royce Da 5’9” and Pharoahe Monch sound elated to be privileged with such heat, they are; if the DJ Premier scratching on “The Matrix” feels like torch-passing, it probably is. And if Tronic continues to collect dust in record store bins, that’s a shame. Black Milk might never stand equal in stature with the Neptunes or Just Blaze, but he seems to wake each day with fervent aspirations to eclipse the works of even the most canonical producers. Bless his heart.

Colin McGowan

45 :: Gillian Welch

Time (The Revelator)

(Acony; 2001)

As of this writing, the Wikipedia page on Time (The Revelator) confers legitimacy on it by referencing the opinion of, of all people, Devendra Banhart. Fuck that. It’s a sad reminder that sometimes the main problem with indie appreciation of folk or country is that it frequently relies more on quirks and image than on, say, writing the best goddamn songs that anybody has ever heard ever. Maybe Welch’s insistence on not being a personality (or worse, since she’s a she, a sex symbol) is the reason she’s not as famous as she should absolutely be? Well, that and the fact that all Bob Dylan has to do is release an album to win a Grammy, even despite better albums like this. Because this is one of those increasingly rare albums that should be famous for everybody. Well, maybe it’s a might bit depressing for a family BBQ, but I suspect even my track suit-wearing Granny (accessorized with diamonds, of course) would give up the ghost on her Mario Lanza fetish if she understood how to get this disc playing in the unused CD player my uncle bought her like twenty years ago. Seriously: anybody want a vintage boom box? It looks hilarious stuffed next to bronze Jesus and Mary statues and those painted, wood-carved sailor heads on the walls. Though I think the atmosphere of this album would only be even more enhanced by the ingrained scent of mint, garlic, and cinnamon that pervades my grandparent’s kitchen.

But maybe this album is a bronze statue of Jesus, at least in relation to everything else on this list. It’s tied with Giddimani as the most thoroughly old school album we’re pimping, but again I think that’s more about the way country music is viewed than it is about anything real having to do with this album. The music of Gillian Welch and her co-conspirator David Rawlings sounds only vaguely and circumstantially like anything from the ’70s, and certainly not like the refined Nashville production of the ’80s or ’90s. Hell, Welch’s ’90s albums Revival (1996) and Hell Among the Yearlings (1998) sound caustic next to contemporary pop country like Shania Twain. And while I guess to a certain extent you might frame some of the longer instrumental passages on Time (The Revelator) as Neil Young guitar solo acoustic-reduxes, they only resemble that as much as they resemble contemporary post-rock jams. Listen to the way Rawling’s production captures the very grain of their guitars in his production. Listening to this album is like having a pillow of luthiered ash and a blanket of Welch’s voice. Or maybe a tombstone and six feet of dirt. Because this album is an epic eulogy, and yes it’s spiritual, but it seeths backwards and forwards across American history with a demure snarl that would rather rumble when it might be justified to shout. And it stands toe to toe with other albums of its ilk. I mean, I like Iron & Wine as much as anybody, but his epic “Passing Afternoon” sounds silly next to “I Dream a Highway.” I also suspect if I See a Darkness hadn’t been released only two years before this this is the album we’d be talking about like we talk about that one. Harsh, mournful, melancholic, and frail, Time (The Revelator)‘s greatest accomplishment is how it seems to chronicle a life lived and ended in the space of 52 minutes, and capture all the emotions of that experience. Hell, it took Six Feet Under five seasons to do the same thing, and like that show, this shit is endlessly comforting and chilling at the same time.

Mark Abraham

44 :: Stars of the Lid

The Tired Sounds of Stars of the Lid

(Kranky; 2001)

We grow up with songs; we’re bred on verses and choruses, bridges and outros, on guitar riffs and drum patterns. We inhale structures because by knowing structures we can recognize logical ends, like diplomas and degrees—we can build towards obvious success. But sometimes we forget to unhinge ourselves, forget that alternate routes, other strategies, different and compelling architectures, exist toward reaching similar ends; Stars of the Lid do not. The duo, formed by Brian McBride and Adam Wiltzie in Texas, obviously isn’t the first to embrace the less linear policies of ambient and drone, but in this new millennium it’s arguably the best. Calling Stars of the Lid “patient” is an understatement: with six years between their last two records, they’ve built a catalog around vastly affected guitar sounds, crescents and valleys of volume, and the swirling hum of treated strings and horns, creating pieces intuitive in their composition and empirical in their effect.

So, with The Tired Sounds of Stars of the Lid, the band opened up the new decade upon a marvelously conceived record, one perhaps more indebted to oneiric cadence, tone, and structure than even its title could admit. Still, the record is dark and captivating without ever slipping into melodrama; achieves beauty and calm without ever becoming innocuous. And meanwhile, their music has served as an important touchstone for several other genres developing similar scopes within the opening of the decade, ranging from post-rock to noise and back to the familiar territory of drone. Considering both its extended multi-part suites and deceptively simple stand alone pieces, The Tired Sounds remains a distilled (over three LPs, that is) summation of the group’s interests in inhumanly measured, achingly layered, and subliminally affecting music. How deep this stuff will worm its way into one’s subconscious may be a matter of individual patience, but given how effortlessly Stars of the Lid can inhabit that realm, it may not be a question of how deep it can go, but for how long—one decade down, a lifetime of repeated listening still available.

Andre Perry

43 :: Mountain Goats

The Sunset Tree

(4AD; 2006)

Even three years before its release, The Sunset Tree would have been impossible to anticipate. The Mountain Goats—then still largely just singer-songwriter John Darnielle—did not deal in autobiography or even in studio recordings. However, after signing to 4AD, his work became increasingly unpredictable: 2002’s Tallahassee, his debut for the label, killed off characters he’d been using since his earliest days as a songwriter; 2004’s We Shall All Be Healed loosely fictionalized his own experiences surrounding methamphetamine; and then, with The Sunset Tree, Darnielle examined his relationship with his abusive stepfather in unrelenting, astounding detail.

Darnielle’s most unflinchingly personal album also, somewhat oddly, yields one of his most immediate and accessible songs, “This Year,” with its anthemic “I am going to make it / Through this year / If it kills me!” chorus. Meanwhile, the rest of the album sees him confront memory and anger as affectingly from the perspective of his childhood and adolescence as he does from the point of view of one exploring it decades later. It begins in a hotel room on “You Or Your Memory” and ends, perfectly, at “Pale Green Things,” where he addresses both his stepfather’s death and the one positive memory he chooses to air, the album lending itself far more to compassion than to simply lashing out. And rarely does Darnielle sound as joyous as he does on this album’s upbeat numbers, even when they almost always end in threatened or realized violence.

Of course, it’s not just about the lyrics. Darnielle’s singing, John Vanderslice’s production, Franklin Bruno and Erik Friedlander’s stunning contributions to the arrangements, moments like the piano’s sudden intrusion in “Dinu Lipatti’s Bones” and the delicacy of “Song For Dennis Brown”—all show considerable growth, and, coupled with Darnielle being at the top of his game as a songwriter, all contribute to The Sunset Tree being the strongest Mountain Goats effort in a decade full of contenders.

Andrew Hall

42 :: Shins

Chutes Too Narrow

(Sub Pop; 2003)

What can you really say about the Shins at this point? I guess the most succinct way to put it is that they were one neo-schmaltz indie romance away from being the coolest band on the planet this decade. Inevitable Braffian pisstakes aside, the Shins’ influence on the past ten years has been both positive and salient. “Caring is Creepy” is pop axiom; “New Slang” is pop axiom; they were such from the moment of inception. My man Braff, whatever you may think of his mopey buffoonery, acknowledged this at an early stage, allowing these crystalline masterpieces to upstage his actors’ antics at times more than they underscored them.

In fact, if the aughts were the decade of indie—and Pitchfork hath decreed it so—then James Mercer and his squad have as rightful a claim to the top of the heap as any other pretender. Sure, it’s likely that with the technological democratization of all types of music, music players, and all things musical no band will ever again rule the whole of the landscape of Music the way that Radiohead did for so many of us at the close of the ’90s. But allow me to present, internet readership, the Shins—who, like Radiohead, spent the whole of a decade crafting a few well-spaced classics that underpinned an entire scene of their own making while fashioning them internationally venerated rock stars in the process.

The true accomplishments of these household names, other than albums like Chutes Too Narrow, is that throughout their blastoff into the pantheon they were able to maintain the style and willingness to experiment that stoked the ardor of drooling fanboys at the ride’s outset. That’s why this is one of the handful of bands that sparked spirited debate about which of their releases were to be included in this list (if not, gasp, both). And as for why I’m not going into the details of the Shinsian innovation, or the feather light texture of their sizable stable of songs that are endlessly approximated but never quite equaled, or the perfectly good reasons Chutes Too Narrow eventually won out over Oh, Inverted World (2001)…well, if you’re reading this you’re almost certainly hip to this band and record already, assuming you didn’t fuck up a Google search for shin splints or something. So, back to my initial question: what really can be said about the Shins at this point? Um: the guy who played drums on this album makes a mean sopaipilla.

Eric Sams

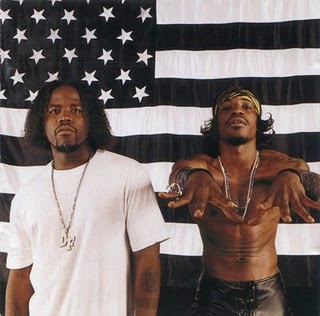

41 :: OutKast

Stankonia

(La Face; 2000)

In 2007 the Glow’s Chet Betz named Andre 3000 “Guest Rapper of the Year,” and when we heard his verse on “Royal Flush” the next year we knew this praise was righteous. Dre gave us “Hey Ya!” in 2003 and with Big Boi he’s dropped top-flight hip-hop since their #1 hit “Playa’s Ball” in 1993. Sure, we also had Idlewild (2006), but in broad strokes the fifteen years in which OutKast have been crushing it have been good to us. Arriving in the middle of this indomitable run, Stankonia is a masterpiece of rapidfire brilliance that simultaneously solidified OutKast’s stature as critical darlings and a mainstream commercial force.

The opposites-attract structure of the duo’s work that became manifest and extreme with Speakerboxxx/The Love Below (2003) is wonderfully tense and subtle here. To rehearse the myth: Big Boi—hard-nosed and traditional baritone—keeps Andre 3000 grounded while Dre—imaginative and experimental tenor—pushes Big Boi out of his comfort zone. Each man has his virtues, but together they are much, much more than the sum of their parts. This pattern repeats itself over and over as Stankonia fuses dichotomous terms, and the spectrum in between, into a scrambled, shaking singularity, always threatening to break apart under the pressure. Accessibility is smashed into adventurous experimentalism, rock guitar crunch collides with G-funk slink, live-sounding drums are melded into programmed beats. The album includes the straight up, feel-it-on-first-listen hip-hop of “So Fresh, So Clean” but also “?,” a theremin-soaked blipfest that takes some work to love. The album won Grammys, critical acclaim, and universal acceptance. When these oppositions exploded with Speakerboxxx/The Love Below tremendous creative energy was released, yet something fundamental was lost. The sheer comprehensiveness of the OutKast vision—arms spread to embrace the universe—disappeared in a landslide of curios and sidetracks.

With such a diversity of strengths, it is no wonder that Stankonia contains amongst its more offbeat album tracks some stone cold classic singles. “B.O.B.” pits drum’n’bass beats against psych guitar and group-chant hooks against blindingly fast lyricism. It’s hip-hop gone punk, but as alluringly insane as that sounds, it’s a paper tiger next to “Ms. Jackson,” a song so good I’d sacrifice the entire catalog of some very good rappers to ensure its safety. A laid back, fucked up, whimsical, and just plain bangin’ beat underpins the leap-crouch hook and withering verses. Its fusion of noise, humour, and collage songwriting—the hook has four or five distinct “vocal modes” in one melodic line; the beat quotes Wagner’s “Bridal Chorus,” aka “Here Comes The Bride”—with more meat-and-potatoes elements in a thrilling rapprochement between the weird and the familiar. Deftly paced and containing more classic moments than any one track deserves, “Ms. Jackson” has a plausible claim to be OutKast’s finest achievement, and in a career with so many highlights it’s difficult to imagine higher praise.