Features | Lists

By The Staff

30 :: Daft Punk

Discovery

(Virgin; 2001)

Discovery is one of those albums to which your kids (or if you’ve already got them, their kids), upon ascending into their teen years, will have a transitory reaction. Where once they would sing along with it in the car with you—you feeling very hip as a result—soon they will make fun of you for throwing it on with bass-boost cranked. The Nintendo-sleaze of “Short Circuit,” the all-out vibrating pleasure-center massage of each of “Crescendolls”’ perfect cadences, the way “One More Time” sounds like someone got their hands on too many vodka coolers and the Cher machine: to the burgeoning savant, these can’t mean anything good. But the assumption buried above, the reason you’ll be paying ophthalmologists to pop a younger generation’s eyes back into the sockets after they roll them too hard, is because when you have kids—whenever you have kids—you’re still going to be listening to this album. That’s an official prediction. And that’s okay, lamo-parent, for a couple of reasons.

First, good as they may be, many of the other albums on this list are going to crack, peel, and flake away with exposure to coming decades, especially since torrential present and future outflow of music means this next decade will pass like dogs’ years, reducing the lifespan of the average album to a moment: now rustling across the tympanic membrane; now gone. Considering that Discovery seems to have the consistency of cotton candy, it’s surprising that it’s held its ground for a decade already. But these songs have been baked into party culture and cling to the kind of late night disco-ball excitement that ramps up right before you step out the front door a little late on a Friday. Daft Punk taught me how to dance and how to have a crush on someone when I became single for the first time in my adult life. At this point, Daft Punk is pretty much my older sister.

And second, one of Discovery‘s strengths is its ability to acknowledge and appreciate what others have done right. Many of the great moments on the album were pulled from funk and disco tracks that have fallen into obscurity and/or disrepute (apologies to Barry Manilow), and credit goes to Daft Punk for recognizing, appreciating, and then tweaking (but not too much!) that source material with a witch doctors’ sensibility that leads them to rip the hearts out of other songs and hold them up beating harder than before. They know how to manipulate that beat for maximum effect, kicking it in, cutting it out, and ramping it up until the low end has been battered from every angle possible with nothing more than a four-on-the-floor bass drum pound (all this despite an admittedly odd mastering job). And so, when your kids get old enough to start their own bands, you know someone’s unprejudiced love of music is going to scale the depths of cheesiness and dig this thing out, buy a vocoder, grab some friends, vintage synths, and Manilow, and start the whole thing all over again. At which point you will be hip again, one more time.

Jessica Faulds

29 :: Fugazi

The Argument

(Discord; 2001)

One of the best scenes in Jem Cohen’s 1998 Fugazi documentary Instrument is the one where Guy Picciotto calls out a slam dancing bully as an “ice cream eating motherfucker.” But a more telling scene of the band’s personality involves Ian Mackaye modestly stating that the only real aim of Fugazi is to produce “heavy guitar music.” Though in one way such a statement sells his band ridiculously short (one can imagine Chad Kroeger saying the same about Nickelback), over ten years later it’s hard to imagine Mackaye didn’t see The Argument coming.

In terms of using guitar-based punk rock as a jump off point to explore dub-heavy psychedelia and white noise, the only band worth mentioning in the same breath as Fugazi is maybe Mission of Burma. But that band has yet to produce a record as subtle as The Argument, Fugazi’s last record prior to their “hiatus,” and arguably their best attempt at reconciling that “heavy guitar music” with the spooky dub experiments they’d been toying around with as far back as 1991’s Steady Diet of Nothing. The former mostly takes up residence in the album’s first third with Mackaye’s vitriolic anti-gentrification screed in “Cashout” and the hard charging one-two of Picciotto’s “Full Disclosure” and Mackaye’s “Epic Problem,” both of which follow in the time-honored Fugazi tradition of combining steel wool guitar drive with misheard lyrics. “Full Disclosure” is downright catchy even, taking full advantage of Picciotto’s fake British accent for the completely unexpected three-part harmonies after the bridge.

But the heart of The Argument lies in the album’s eerie mid-section, a collection of quiet experiments purposely pushed out of step with what the band had seemingly been doing for over a decade. Picciotto’s vocals in “Strangelight,” for example, never rise above a whisper, and it peaks with the furious bowing of a cello, making for something of a chamber-dub symphony. The bass-driven lull of the Joe Lally-led “The Kill” has a predecessor in Steady Diet track “Long Division,” and “Oh” gets herky-jerky like Gang of Four in their prime with an especially bratty Picciotto dictating a Tyler Durden-style fantasy (“Message to the partners / I’m changing all the locks / I’m pissing on your modems / I’m shredding all the stock!”) before performing rounds of “Thank you sir may I have another!” with Mackaye.

The remainder of The Argument exemplifies Fugazi’s willingness to defy punk’s staid expectations, whether by employing a second drummer on “Ex-Spectator” or introducing feverishly strummed flamenco guitar on “Nightshop.” And in terms of a shared spirit in wrecking boundaries, it’s not for nothing that Picciotto was put in charge of producing the final (and underrated) Blood Brothers album. To the uninitiated, Fugazi is still probably best known for keeping their ticket prices hovering around five bucks and for berating slam dancers from the stage. But for most, they were easily the least conventional, and arguably most important, band to wear the “punk rock” tag throughout the ’90s. And if The Argument does indeed end up being the final Fugazi album, they can at least claim to have never made a bad one, retiring at the height of their powers.

David M. Goldstein

28 :: Gang Gang Dance

Saint Dymphna

(Social Registery; 2008)

Whereas Since I Left You (2000) predicted and preemptively embarrassed the deluge of sample-heavy party music of the aughts, Saint Dymphna did the reverse: it collected the detritus of the decade’s often-questionable obsessions (eclecticism as Myspace web cred, rote electro-tribal mash) and turned it into awesome. In hindsight what’s most shocking about Saint Dymphna is not any particular track or conceit contained therein (though I could name a few), but just how much Gang Gang Dance accomplish in the album’s 44 minute runtime. Well, that and how uniformly superior the material is to that of their supposed peers. This is, of course, a testament to the band’s musical prowess and omnivorous tastes: most reviews breathlessly attempt to spot every genre and East Asian instrument on which Saint Dymphna lays its sweaty fingers—to no avail.

I’m not going to play that game, nor will I try to convince you that Saint Dymphna is a) a dance album (it is), b) worthy of its patron’s namesake (well, sure), or c) the best album Animal Collective didn’t release in 2008 (duh). Instead, let’s acknowledge that, however you interpret it, this album provides a kinetic energy all its own; this energy often proves too much to handle, as the album’s many pieces expand and contract into one another like a heaving giant or a supernova whose destruction rips a hole in time-space. This, at least, is what “Desert Storm” does. Elsewhere, GGD perfect the art of levitation: “First Communion” makes the most goosebump-inducing entrance since “NY State of Mind,” with all the hyperbole that implies. Speaking of which, there’s rap on this album, though it’s totally in service to what makes Gang Gang Dance Gang Gang Dance: uncompromising artistic vision leavened by the feeling that Liz Bougatsos is grinning at you, front teeth slightly ajar, from behind the curtain.

Traviss Cassidy

27 :: My Morning Jacket

At Dawn

(Darla; 2001)

At Dawn is an almost intimidatingly truthful record, each song hewing emotions of such diamond-cutting clarity one can feel exhausted just listening to it. Mostly, it is a triumph of a craftsmanship. Three minutes into the second song, Jim James is singing, “You only gotta dance with me” above slow-motion heartbreak drum rolls and chiming flashbulb guitar countermelodies, the first in a staggering succession of crescendoes that the album will subject the listener’s feeble human heart to. You are all like swooning in your chair to it, and it is the second song, and one of the shortest. From there, the band is off, normally letting the profundity of James’ tenor seal the deal (I think you can hear his neurons firing in the stillness of “Phone Went West”) but also so instrumentally robust they’re just as comfortable letting a plaintive guitar line stumble drunkenly home (“X-Mas Curtain”) or to flick cross-harp like a match against kerosene blues licks (“Honest Man”). The band feels almost inhumanly powerful, mountainously old, qualities they’d capitalize upon on the thunderous It Still Moves and parody with varying success thereafter. But there is no irony here, just cleaned up Southern boys looking to make good—and then let loose—on prom night.

Clayton Purdom

26 :: Keith Fullerton Whitman

Lisbon EP

(Kranky; 2006)

Cutting to the contentious chase: Lisbon is an important record, fully deserving of a dropped I-bomb with all of its fuck-you problematic connotations and contestability. This record is game-changing, a seismic event along ambient music’s sleepy timeline. It’s nothing less than a landmark. Whitman is due recognition for creating an album that is at once niche gold for ambient fans and unanimously attention-arresting for listeners who have never listened to ambient in their life. In any discussion about the most important records in the genre, Lisbon deserves to be mentioned alongside Music for Airports (1978) and Selected Ambient Works (1992). So there are the stakes. Here’s how Whitman did it:

If ambient is about space and time and engaged listening and reflection, Lisbon is about sacrificing the two former in service of contemporized versions of the two latter—about tethering that blank infinity that Eno posited and ripping it down around the listener’s ears without for one second sacrificing ambient’s critical cornerstones. Eno envisioned ambient music as a pseudo-political response to the muzak-ing of music, the rendering of art into fodder for the interstitial; not surprising, considering the staggering commercialism ready to culminate in 1980s pop music. So ambient became an effective tool for meta-commentary and critique, forgoing the exhausted fumes of punk cynicism and glam’s ego imposition (which made ambient as much about self-reflection for Eno as about reflection in general). It was well positioned as something uniquely accessible: as a wordless genre, it is about whatever you need it to be about which; if you’re a politically or socially aware person, it is also what a lot of people will need it to be about, which is the whole point of its politics of reflection. Lisbon, while stylistically distinct from the serene wave of that early Eno, harnesses that same efficacy of purpose and gives us a post-9/11 update. The record contains the shuddering, paranoid, beauteous, complex mood of 2006’s post-millennial anxiety with all of the vacillation and monumentalism and drama accorded the times. It’s as if Lisbon and William Basinski’s Disintegration Loops were twin offspring of the whole damned decade’s subterranean psychology.

In CMG’s original review of the record and subsequent year-end write-up (a top ten spot for a 40 minute piece of ambient, natch) we were right to reference the physical, or rather the vast insufficiency of language; the fact that writing the words “it makes me want to weep” will go a very small fucking way towards making you feel the way you feel when you listen to this music (which is: like weeping). This isn’t forty minutes of noise, or even forty minutes of music, not by a long-shot. This communicates on a guttural and terrifying and transcendent level, reverberates in the bones and makes suddenly very feasible the notion that there are other people in the world who are experiencing the same visceral, intense feelings that you are. Dare I use the word “zeitgeist” on an album that doesn’t point and declare with explicit dumbness exactly who it’s for and what it’s about? And isn’t that exactly what makes Lisbon zeitgeistal?

This is how a 40-plus minute piece makes an environment its own, ties itself so intimately to one’s experiences that it evokes those environments with ease and in remarkable detail. You, as a product of your time, are carrying around in your head all of your little part of the world’s socialized flaws and excesses; this music is both canvas for those flaws and is the product of some similar set. It is the much-required 2000+ update to that fundamental and elegant raison d’etre of ambient music as conceived, all those years ago, by Eno. It allows you to reflect, and it reflects back at you the decade’s troubled thoughts. It’s canonical, and a classic, and yes: a fuck-you important record.

Conrad Amenta

25 :: Frog Eyes

Tears of the Valedictorian

(Absolutely Kosher; 2007)

…oh, and speaking of post-millennial anxiety and its complex figureheads, how about Carey Mercer, that mad spitting preacher who portends dark 21st Century raptures? I argue, with all of the futile attempts at clarity that I can muster, that there was no musician more lyrically invested in our young century’s cathartic trauma and utter absurdity. Rendered as conversation and narrative among personalities not so much split as splintered, Mercer screams lines like “And you sing that song that the general sings to the dawn” and “He said, ‘I’ll see you in the morning’ / and now the night night night night sails in the morning” with all of the passion accorded our years’ frustrated and serpentine coda. “Caravan Breakers, They Prey on the Weak and the Old” conjures a carnivalesque frontier justice, Melanie Campbell’s thudding drumming a titanium backbone to the band’s unrelenting dynamism. But it’s a line like “He called his sister / he called his brother / he got skipped father / he scorned his mother” that paint the everyday with the same tortured brush. All is tainted, all is romantic; the sky and its threats are endless.

“Idle Songs” and “Stockades” may put Frog Eyes among those few bands to reinvest the stagnant punk project with some quasi-relevance, but their most undeniable resonance is in their long form numbers, which rely on a combination of their characteristically intricate and on-a-dime guitar work but followed by swaths of luxuriously textural builds and repetition; the aforementioned “Caravan Breakers” is an example—its joyous “Woo hoo! / I want a belly fully of gold!” born along by explosion after explosion of messy melody—but “Bushels” is both centerpiece to the album and even a mix of the decade’s important music; this blurb could be about “Bushels” alone and still go some way to communicating what it is about Frog Eyes that stabs away at corroded walls to the vulnerability beneath. Consider this line, correctly highlighted by Scott and Dom in their appropriately lavish review: “And like a drunken and besotten father figure of old / Who was pushed on an ice wedge out to sea / And he trembles and he trembles and he puts his heart on tremble / And he profits from his guilty memories.” It almost sounds like a hope for closure after this decade we’ve had.

Mercer’s full-throated love of language’s play, the ability to twist dogma in on itself and render surreal the sensate (“the weeds deign to sigh / but the admiral’s chicken / the general’s chicken / how painful they rise”) are the key to his music’s dystopian relevance—what better way than to make torturous those satire-killing years of absurdity, to acknowledge that, sometimes, there’s little benefit in context and sense? While his Blackout Beach project may feature his lyricism more prominently, and Swan Lake offers the comedy of seeing two world class lyricists in Mercer and Spencer Krug meditate alongside Dan Bejar and his first-year poetry, it’s Frog Eyes that offers Mercer the broadest canvas—and Tears of the Valedictorian that represents the fullest exaltation from those damned and damning lungs.

Conrad Amenta

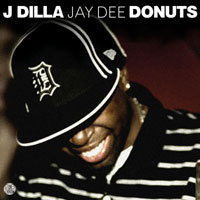

24 :: J Dilla

Donuts

(Stones Throw; 2006)

Donuts sounds like kissing tastes. Not intoxicated frenching in a stairwell, but restrained, impassioned smooching on a leisurely morning—you called off work to cuddle until 11 AM, and perhaps the smell of bacon drifts into the bedroom just as the pains from too many intoxicants the night before begin to dwindle. Donuts, like the food, is best enjoyed in the morning with cigarettes, or coffee, or at least one person you hold dear. It is communalism as aural incarnate; within its ether, all things blend—doo-wop singers with a broken piano, a southern orator with a cacophonous guitar, a childhood toy with marijuana—and slip lazily beneath fault lines of percussion to emerge anew, precious stones excavated from beneath the crust of Dilla’s New Era-capped dome. But in the same manner amethysts and sapphires only temporarily adorn the ears and fingers of the populace, one day returning to their rightful resting place amongst the dirt and clay, again part of something infinitely larger than a trophy wife’s bracelet, these 90-second bursts of inventiveness congeal into thirty minutes of quiet joy when digested in full. Because diamonds are shiny, but the Earth’s beauty is immense, right? And mouths were built to mingle. Have a donut or 31, I implore you. But remember to share.

Colin McGowan

23 :: Neko Case

Fox Confessor Brings the Flood

(Anti-; 2006)

Fox Confessor Brings the Flood is a thematic behemoth of a record: as grandiloquent as a myth, as black as a God-shaped hole. We tend to talk about Neko Case like this, in terms of bigness—the sweeping scale of her artistic vision; the unstoppable, gale-force intensity of her voice (which, if someone hasn’t already looked into it as a source of renewable energy, get on that; I’m pretty sure it could power a small town). Fox Confessor is, after all, a record that comes to us with its own self-made mythology, and when the big picture is that big, zooming in on any one piece of it tends to feel a bit reductive. But it isn’t; the rare thing about Neko—and on Fox Confessor more than maybe any of the other wonderful records she put out this decade—is that she somehow finds an impossible balance between the forest and the trees. So even among the bigness of this record and the kind of full-scale devastation it wreaks, it is also able to inflict tinier, more localized injuries.

Think about the things in this decade that pop music has taught us about “empowerment” and “independent women,” both of which have been worn into rather empty truisms; just try and think of the latter without conjuring a Beyonce-endorsed commercial for Charlie’s Angels. I could have another you in a minute, matter of fact he’ll be here in a minute / If you like it then you shoulda put a ring on it. This is what empowerment sounded like in the aughts, at least if you were listening to pop radio. But there were other records too, records beckoning us to consider the fact that Beyonce wasn’t even telling us half the truth. Since I was born into a world where Liz Phair had already grown tired of being whip-smart, my Exile in Guyville (1993)—as in the first record to suggest to me the possibility that sex, marriage, and love are not unequivocally redemptive; that being an independent person often comes at the expense of loneliness and a constant yearning after impossibilities; the first record, in short, to un-teach me all the lessons that every other pop song had instilled in my brain—was actually Fox Confessor Brings the Flood.

The tragic thing about all the characters Case brings to life on Fox Confessor is that they’re all completely, cosmically fucked, and all their resistance to this fact only makes them worse for the wear. “Go on, go on, scream and cry / You’re miles from where anyone can hear you,” Case wails on “Star Witness,” one of the most gorgeously heartbreaking songs she’s ever written. This is a record of twelve stammering confessions to the lying, scheming Fox, twelve tales of people whose expression of their own dissatisfaction ends up being the chief instrument of their inevitable demise. Yeah, shit’s that bleak.

Forget Phair’s disillusioned refrain “Whatever happened to a boyfriend?”, this record seems to say: we are all onto bigger and sadder questions. Whatever happened to the very idea of love, God, truth, pop music? Or, as Neko asks to end the title track, a towering question mark spiraling like smoke towards the vacant heavens, “Will there be nothing above me to put my faith in?” I see something, I think, hidden in this record’s brightest corners: a lingering beauty in the confessions themselves, sung by a heavenly voice; the faintest suggestion that there is something noble in holding out for that teenage feeling, and all that stupid old shit like letters and sodas.

Lindsay Zoladz

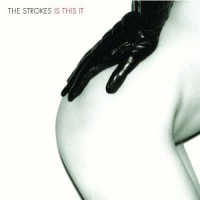

22 :: Strokes

Is This It

(RCA; 2001)

Nearly nine years after its release, it’s easy to remember Is This It as if it had emerged pre-formed and fully realized from the New York semi-underground. But it wasn’t until the release of Julian Casablancas’s solo album Phrazes of the Young (2009) that the precariousness of the tightwire act the Strokes were playing—and the magnitude of their success—became fully apparent. Turns out that Casablancas wasn’t born cool; Phrazes is downright gaudy, and though that that tendency lurks underneath Is This It‘s inexorable groove, the Strokes’ debut now seems all the more a carefully and tightly wound ball of energy with no misplaced notes, no lapses in taste, and no indulgent asides. Every piece is aligned precisely and every pluck, strum, beat, and muffled intonation moves in perfect lockstep. There’s some Glenn Gould in the metronomic relentlessness of it all.

Of course, one can’t approach Is This It without imagining the Strokes honing their skills on the same Lower East Side as their musical influences, cultivating a bratty, haughty image that smacks of playing dress-up. They’re New Yorkers and apparently don’t give a fuck what you think—they’re the second coming of Lou Reed, the Vibrators, Television, the Modern Lovers, the Stooges. (They were also the target of a major label bidding war.) But what Is This It truly seems to evoke, after almost a decade is, for me and for, I suspect, many people, nothing less than the 2000s in all its ugliness and glory. “New York City Cops” is the album’s peppiest, most joyful track and yet it still drags up memories of buildings falling and bones crushing. Is This It is a relic of college parties, train rides, hungover afternoons, iPods when they were expensive oddities, and now of a time before attitudes got too jaded, when relative tranquility hadn’t yet given to an adulthood amid terror, war, and recession. Or maybe Is This It was just a giant back-scratching session and listeners are bystanders lucky enough to enjoy the results. Or maybe it’s all of this—there’s a hell of a lot crammed into those good old three-minute pop songs, even if the Strokes didn’t mean it.

Skip Perry

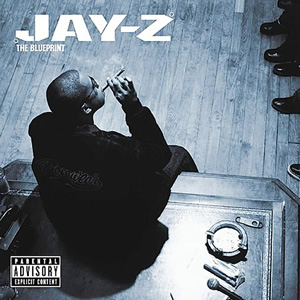

21 :: Jay-Z

The Blueprint

(Roc-A-Fella/Island/Def Jam; 2001)

The Blueprint is not the best hip-hop album of the decade, but it’s certainly the biggest. It set out to be colossal, so it’s a good thing Jay’s persona at that point in his career towered over everyone in sight. The only bigger rappers were dead, and the only beef bigger than the one detailed in “The Takeover” was six feet underground. In large part through his own self-mythologizing, Jay filled the void left by the death of Notorious B.I.G. and with this record secured his status as heir. The record—and its lead single “H to the Izzo”—hit so big that it made the careers of now-essential hip hop producers Kanye West (at the time a lowly working producer) and Just Blaze. Bink, Timbaland, Poke and Tone, and Eminem all turn in some of the best work of any producer in the game, but these few collaborators—however distinguished in their own right—here only ride Jay’s coattails. Without the need for guest MCs (Em is the exception that proves the rule) to prop him up, Jay famously recorded the lyrics sans pen and paper in two heady days in 2001, thus achieving the greatest hot-fire-per-hour rate in rap history. With more line-for-line lyrical muscle than any album in his catalogue (save perhaps the all-time classic Reasonable Doubt [1996]), The Blueprint casts a dark shadow over the entire decade, as mainstream rap contemporaries and even Jay himself struggle to this day to match it.

There are consistent rap albums and then there’s The Blueprint on some next level shit, with producers maintaining a brain-scrambling level of ass-whoop throughout. Kanye and Just Blaze craft a game-changing sound based in classic soul samples, defying the synthy Timbalandisms that dominated radio and hip-hop at the time. More importantly, these beats bang. They bang with a mythical, adamantium-hard force. Not to be outdone, Timbaland chimes in with “Hola’ Hovito,” a mad romp of click-bounce guitars and wide, low bass that has a solid claim on the top five in an impossibly distinguished production catalog. Eminem’s contribution is one of the few things of his that hasn’t aged poorly, so listen to him stand toe-to-toe with Jay to see what all that fuss was about. Every track is a hit, and Jay never misses: he has the taste and judgment to choose the finest beats out there and the force of personality to bring forth the very best in his collaborators. The result is an album that aimed to put rap in a chokehold, and ended up establishing Jay-Z as the preeminent rapper of his generation.