Features | Lists

By The Staff

20 :: AGF

DANCE FLOOR DRACHEN

(AGF Producktion)

DANCE FLOOR DRACHEN levels a rapid course. Its frightening nature is that the course presents with increasing diversions or loops-back and -through what eventually turns out to be one big interdependent bolus of undigested food for thought.

The record’s brilliant is what I mean. Brilliant because it’s cute. Most of its ideas are weird and speculative, yet those same ideas are axiomed in the critique and free manipulation of stuff that’s been going since whenever you decided to man-up and press play. This is music as cultural critique as cultural dementia—we note ourselves losing track, by degrees, of what the hell is going on because what is going on is kinda already-familiar but not-quite-there, y’know? The effect is sound as an ontological thought-proof: infinitely wise and obviously young, like if all the music ever passed through some synthetic membrane and then that membrane, fucked, got melted to this, DANCE FLOOR DRACHEN, a really beautiful beats-me masterpiece.

Its gross cerebral breadth and icy logic means that it sort of makes everything it sounds like an episode of relative malfunction, or an aborted attempt. This, you get, is the real rational alphabeat, made by a person who knows the dialect and the trickery, plus has the insouciance needed to make it all quite mean. “Buy me out” or “Buy me, out” or what exactly? It’s as if we’re following all the different worms right back into the can, every track a startling multi-form clusterfuck that plays devil through diaspora-in-reverse. Antye’s through-the-glass delivery is strangely bewitching and, like the album in general, has a simple gravity: at once teasingly withdrawn but loaded, the further you fall in, with a sense of accelerating meaning and purpose.

Alan Baban

19 :: Cut Copy

In Ghost Colours

(Modular)

Every summer deserves its trophy, so here’s one for the competitors who studied the moves of the Junior Boys and then tweaked them to Jumpin’ James Murphy. It may have been denounced by the scowlers as “summery dance music” but that hasn’t stopped Dan Whitford’s computer troupe from taking the globe by storm, raining the musical equivalent of batshit Pacino quotes upon anyone hungry for, uh, summery dance music. Spreading like an outbreak of haircuts and caring less about fashion than the French Foreign Legion, Cut Slash Slash Slash Copy pasted a hunk of New Order, a zodiac of synthesizers, and a shitload of goodtime elbow grease into Colours to create 2008’s perfect crossover, smiling while the world got giddy and fell about attempting the perfect Melbourne Shuffle. Around this time, I quickly rang my Down Under brother and asked him how CC were faring in Queensland—his response was to croak “You’re a fuck-knuckle,” which perhaps says more about late-night time differences than it does the substance of In Ghost Colours. Still, even the crustiest of rock-fed repairmen would be hard pushed not to melt, crystallize and then sublimate as “Voices In Quartz” becomes “Hearts On Fire.” Whitford’s layering of pill-chomping electropop with hazy wafers of comedown forms a formidable vertebral column, and as any bookbinder or weightlifter worth his salt will tell you, spines are what stop you from being a puddle.

George Bass

18 :: HILOTRONS

Happymatic

(Kelp)

I honestly have no business liking Happymatic. Semi-tongue-in-cheek new wave revivalism? No thanks. Of course, in the long run HILOTRONS represent much more than that; this may be why, despite the fact that they bear substantial similarities to bands touted by several successful contemporary acts, they can’t seem to make it outside of Ottawa. It’s this two degrees of separation between them and say, Vampire Weekend, that puts HILOTRONS on a completely different trajectory. Sure, there’s a fondness for early ’80s pop recordings…as a springboard. “Dominika” sounds a lot like a Police outtake but only if you dismiss that spacey electro break which they still manage to fit in between the main reggae-tinged groove and wrap the whole thing up in a minute-and-a-half.

And most of the brilliance on Happymatic isn’t even that obvious: the band’s recording techniques are so sharp that I’m still catching nuggets. There’s that ending to “Streets of Science” where the synths are so heavily phased as they ascend that you think it’s going to throw the taut rhythm right off and then doesn’t; those dub-inflected backwards melodies that float uneasily in the background of “Lovesuit” and the gorgeous Labradford baritone-guitar lines on the same song; the way the upstroked guitar of “Emergency Street” always seems to hit surprising spots.

And finally, if there’s any pervasive influence throughout the album, it’s not the Police or Devo or Talking Heads but Ennio Morricone. His distinct reverb/chorused guitar is all over “Caught on Video” and the spaghetti western instrumental “Feet First” might as well be a tribute. But the influence is also felt where you least expect it, particularly in the gorgeous cover of Kepler’s “I’m a Parade.” A heart-on-sleeve ballad, it’s not the kind of thing you’d expect to sound like an artist best known for scoring action films but, like Morricone, HILOTRONS seem interested in using slow reverb and rolling percussion to evoke vast landscapes and exaggerated dramatic tension. And like the old man, they’re less interested in following the footsteps of popular culture as they are scoring it. If they have to remain forever on the fringes to do so, so be it.

Joel Elliott

17 :: Roommate

We Were Enchanted

(Plug Research/Shrug)

This is a lot like that last Fog record except even better and sorry, WHY?, but it’ll be a couple years from now before Anticon releases a record that manages even a faint echo of this sort of apotheosis of the current Anticon philosophy. That is, morbid verbosity collapsing under its own weight, words exhausted with their own wordiness, constantly grasping at grim truth with truth proving more elusive than simply “grim,” and finding respite in surrealism’s shambles. With gorgeous post-everything arrangements to match.

Roommate’s forced the bedroom electro-pop of Songs the Animals Taught Us (2005) to evolve into a hard-to-define expanse of strings, horns, group sing-alongs, and a high school’s worth of kids playing canjos, keytar still very included. You can practically hear the birth of new friendships, a quick welling up of collaboration and the spontaneous combustion of creative serendipity in the way that Roommate wrangler Kent Lambert asked a stranger, Mucca Pazza guitarist Jeff Thomas, what he could do for the record and Thomas replied “crazy guitar solos” and there it is: a crazy guitar solo devouring the negative spaces in the crystalline obelisk that is the indomitable “Last Dreams of Summer.” To wit, “Last Dreams of Summer” is 2008’s successor to Frog Eyes’ “Bushels” in the Artsy Indie Jam of the Year category. I don’t know what’s more affecting, the way Lambert almost embarrasses himself whispering earnestly, “In your dreams tonight you will suffer salvation by candlelight / And I will tell you that in hell there are worse things than fire / And the ghost brigades in their slow parade up to heaven / They will sing with a fury that only the Lord can inspire,” or the way that immediately after that hushed intimation all Lambert’s old and new friends come crashing in with their instruments to back him up—and back him up with utter conviction. In a strange, lusher way it reminds me of Slint’s “Washer.” Which is like the best song ever.

But while Slint are more insular and jagged in their melancholy and much more obvious touchstones like Sunset Rubdown and Frog Eyes are more esoteric in the cerebral labyrinths of their chiascuro, Roommate plays to the crowd with the crowd. Because what’s even more affecting than “Last Dreams of Summer” by itself is the crescendo of “Last Dreams of Summer” melting directly into the warmth of “Night,” which is both campfire gathering of Lambert and his friends and Lambert and his friends covering a friend’s (Cody Hennessy aka Rhombus) song. The album title, We Were Enchanted, holds all the keys. It starts with fantasy not as escapism but introspection and ends with a promising new direction for groupthink. Lambert finds enchantment not in fantasy outside of reality but in the strange fantasies that teem beneath reality, the oozing stuff that dreams are made of. To explore this territory on a purely personal level is indulgent in an honorable enough, sabbatical-type way but to join with a host of peers in mining those depths for some kind of transcendent commonality, some communion, some community…that shit’s dangerously close to sublime.

Chet Betz

16 :: Lau Nau

Nukkuu

(Locust)

If We Were Enchanted is a conscious group endeavor to scope out the prospect of some collective oneiric subconscious, then Lau Nau’s Nukkuu is a lonely flight into the realm of the sub-sub. Aptly enough, Nukkuu is Finnish for “sleep,” but Lau Nau exchanges New Age conventions of what makes peaceful or meditative music for a vital approach that’s assimilative of abrasive everyday (or night) sounds, the instrumentation and production mirroring how the rush of cars or wind knocking shit over or the chug of a radiator can be composed by our sinking minds into a more sedating soundtrack than anything by Enya ever. Lau Nau rolls with the punches of chaos that the world dishes out…and keeps rolling and rolling until she’s communicating in waveforms that carry the debris left by your cognitive dissonance when you encounter her calm defiance. What she destroys she brings back to you, in pieces. Thus, the clanging assemblage of the opener pinned together by that bracingly sweet voice—or that same incomprehensible voice fractured into soothing echoes of itself on “Maapahkinapuu” then dressed with incidental noise and backwards loops.

I don’t really know much about Lau Nau nor am I familiar with any of her past work but after hearing Nukkuu I hold her in high regard. This album’s beauty is so singular and absolute that it simply must be the bloodletting of a beautiful soul. For instance, “Painovoimaa, valoa” is beautiful to the point that I don’t even want to talk about it. I don’t think I can. So watch the video and revel in how close to adequately the images describe Lau Nau’s music: something as natural as snow softly manipulated to fall upward; a kitten’s game of playing with yarn transformed into Jean Cocteau-inspired performance art; enough tree shots to make Terence Malick cry; and just the right amount of the unsettling to uproot your perception and settle it on what feels like new ground—or a remembrance of what the Earth once was and a hope for what it could be if somehow reborn. If only in the way that we feel its rhythms when we sleep.

Chet Betz

15 :: Portishead

Third

(Island)

In our review of Third, Clay bemoaned that the drums—Portishead 1.0’s foundational instrument—seemed “underserved” compared to old records. True, most of the beats on Portishead (1997) are fucking great, so I see where he’s going, but: a) Third, the Radical Departure in the Band’s Oeuvre, naturally had to shake up the formula and rely more on, say, seismic guitar riffs and submerged keyboards to avoid becoming a bland rehash job; and b) ohmygod the spastic fills on “Plastic” and the mortar-chiseling assault of “Machine Gun”! If anything, the drums on Third aren’t underserved so much as occasionally understated and often far too alien to really count as “drums” per se, killing when they need to but mostly out of the way when the songs call for it. The bare-bones rhythm on “The Rip,” for example, is metronomic in its simplicity—all the better to highlight Beth Gibbon’s delicately elongated syllables and a gorgeous keyboard arpeggio. And fine, if that’s not your steez, the shattered helicopter blade pattern on “Plastic” should wipe away any doubts about this band’s continued mastery of everything weirdly beat-worthy.

So goes the story for the rest of the band on Third. In order to broaden its reach, Portishead 2.0 has given slightly more peripheral roles to its previous touchstones (percussion, Gibbons’s voice) without stripping them of their awesome power. There are even moments when our shrouded chanteuse doesn’t amaze us merely with her voice’s natural beauty but with the way she fights to say on top of tracks like “Silence” or “Threads” that threaten to consume her spectral croons completely. More than a conscious reinvention, Third is the sound of a band pushing itself to be the best band it can be without falling back on the crutch of familiarity—no matter how awe-inspiring that familiarity may be.

Traviss Cassidy

14 :: The Hospitals

Hairdryer Peace

(Self-released)

Hairdryer Peace sounds like, but is not limited to: storm clouds gathering over my frontal lobe, muddying my synapses, and sending me into a morphine state that causes me to drip spittle like a stroke victim; post-downpour mud taking shape and ruthlessly slaughtering the Strokes; divorce (that’s just a shot in the dark, though). In more literal terms, the Hospitals’ clattering cacophony raves and chokes like someone threw a soundboard in the ocean and recorded Here Comes the Indian as performed by out-of-tune guitars and unglued minds (or, to be more specific, minds never glued in the first place).

Which is why my adoration for this is so walrus blubber thick, why my chintzy furniture melts when this pollutes my ears. The way “This Walls” starts with a discernible bass line that gets subsumed by the sheer weight of tin sirens and slow-motion repetitions as intoxicated assertions (“dude, you gotta believe me—”) like a hapless victim in a zombie flick; The fucking perverted self-high fives I’ve given myself because “Smeared Thinking” should soundtrack my every mental collapse; “Animals Act Natural” is the death of a dear friend as told by the screeching car-parts-turned-shrapnel that punctured his frame: this isn’t fun stuff to evoke. This is uncomfortable like visiting a brother in a mental institution; this is the worst day of my life as sloppily photographed by some pill-popping shutterbug that could give a fuck.

This is where sound goes out to the desert and dies. Noise enters a crowded room and nestles itself next to your lover. Eardrums capitulate and throats try to hum along, because they have to, but in futility, because—have you heard this thing? It should come with a Surgeon General’s warning: “May invoke manic depression.” You haven’t, though? That’s a pity.

Colin McGowan

13 :: Chad VanGaalen

Soft Airplane

(Flemish Eye/Sub Pop)

Quarantined by all sorts of restraining organs but still rupturing at its seams, Soft Airplane is a scarily personal record. Both for me and, I can only assume as a fan and borderline obsessive, for Chad VanGaalen. Between its gluttonous folds is an inordinate wealth of contradiction, sadness, loneliness, exuberance, and challenge, but these are the most readily available finds—in the scorched earth bass thud of “Old Man + The Sea”; in the aimless, loaded pause before the “TMNT Mask” verse, which is its chorus, joins its impossibly solvent beat—and VanGaalen’s voice alone could serve these emotional touchpoints. What’s so devastating, and I don’t use that word lightly, is that interrogating the record, I mean really sitting with it, is an act more than just admitting to the audience’s role in any piece of art—that mutual creation that’s so idealistic to critics—but one of ecstatically witnessing a musician ecstatically reach, and maybe even finger, a concision so thoroughly his own that, in retrospect, it’s safe to say his third album has poked perfection.

Safe, but intimidating, this getting so involved with an album inevitably bred to shame me. I relent at the bridge to “City of Electric Lights,” where no bell strike is wasted, no chord orphaned; I relent at the unnerving curtness of “Molten Light,” a parable, creeping and crepuscular, for parabolic songwriting; and where I relent I’m unduly frightened, each insecurity about my writing and my social life and my talent set in stark relief because, well, VanGaalen has and has made what I want. What I want to make. His response to all this is frank and wild: a worldly intensity meant to salve all doubt about whether a person’s inner turmoil is worth a damn when it only amounts to the stink coming off everyday shit. Meanwhile, he’s quietly weighing the symbols of his career, figuring out how the moon can be a sign of both death and rebirth, or how the stars can be the Sun, or how waking up late can feel freeing and still a symptom of depression, reflection best met in the quotidian, mortality looming as Chad goes to “hang [his] clothes up on the line.” His conclusion, as much a physical destination as an inspiring moment of energy, is simply “When I’m dead / Is when I’ll be free.”

Which isn’t sad as much as it is a totally loaded statement of fact. Soft Airplane intuits every slapstick move and indulgence of everything VanGaalen’s done before and, exploiting whatever tension surfaces by outsourcing his missteps to listeners like me, sustains his work through a sweet and exciting balance. There is simply no other way to describe the first verses of “Rabid Bits of Time,” when blatantly mournful chords, grinding against sheet metal sliding doors, yank VanGaalen’s lyrics into rooms where they don’t fit. “You’ve been dead for years,” he croaks in correct cadence, then: “But you never knew,” which sounds slightly overextended, until “And the rabid bits of time / Have been eating you” confirm that, yes, there is awkwardness in the sinews of this record, never resolved, instead exploded (“Frozen Energon”)…but that’s just how it is: Chad VanGaalen setting fire to his bedroom then quickly putting it out because these things still mean a lot to him. This is what a head-shrinker might call closure.

Dom Sinacola

12 :: The Dodos

Visiter

(Frenchkiss)

I know what you’re thinking: acoustic guitar and a stand-up percussionist, CMG is trying to sell me some Guster bullshit. And we are, except that it’s about as easy to ingest the breadth of trad influences here as it was hard for Guster to make a single listenable moment of music.

We’re still at loggerheads, though, because even trying to describe the Dodos in practical terms gets us into trouble. “Enthusiastic drumming with a full-out indulgence in acoustic guitars” conjures a nightmarish vision of mixtapes made for girls who listen to live Dave Matthews Band albums and Dashboard Confessional, which this is not, though I know some of those girls and even they like the Dodos. Thus, shit becomes even more difficult when it’s understood that the pop sensibilities at work between all of the atrocious bands I’ve mentioned aren’t far removed from the Dodos.

So I’m asking you to step out onto trust’s ledge. To believe, for a moment, that this isn’t our usual shtick, that thing we’ve noticed that you’ve noticed we do, where we fit conch shell to lips and clarion call the avant-heads from beneath piles of Anthony Braxton records and Supersilent albums on laserdisc. This is us recommending an album that mixes upbeat indie pop songs with downbeat ballads, whose greatest transgression against the canon is some occasionally boisterous noise. And we’re not doing it ironically, or as an experiment in semiotics, or as preamble to another faking of our deaths. This is our serious face. And Visiter is an infectious record, eager and passionate about itself while produced well enough to know that every dirty detail of a slapped guitar and wildly vibrating string deserves to be captured. While not the best album of the year it’s certainly one of the most unabashed, a high-wire act of emotions on one’s sleeve that is miraculously pulled-off. Surely one of our least contentious choices here, the Dodos, innocuous though they may seem, may have delivered that common ground of an almost universally likable record.

Conrad Amenta

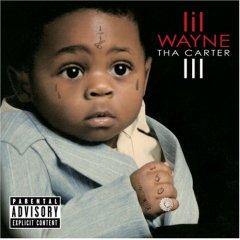

11 :: Lil Wayne

Tha Carter III

(Cash Money)

2008 and Weezy is still reaching for the apex of disgustingness: swallowing the English language whole, allowing his internal chemistry to dismantle it, then shoving a camera down his throat and letting us observe the undulating results. This isn’t a journey inside the mind of Dwayne Carter; it’s a thoroughly documented excursion through his gastrointestinal system. And if that image makes you retch, it should; some of this guck leaves faces green. I refer not to the menstrual blood remarks or the poop jokes but to the agitating pulsations of “Phone Home,” the laziness of “Lollipop,” “La La” not being that “La La.” See, adoration of C3 demands not just acceptance but a warm embrace; Weezy makes this relatively painless by injecting his missteps with the same lethal doses of glee and endearing bombast that pervade his best work. I doubt your significant other really cares intimately about that ingrown toenail you’ve been bitching about, they’re probably just being polite, but if Wayne wants to rap about his recent bout with food poisoning, I’ll listen. His vacation photos are probably swell, too.

Weezy’s expulsion of snot, piss, and, yes, words is so jarring in that it’s great despite having such an abhorrent premise (not to mention the shackles of major label subservience). Sure, all things vapid and vain amalgamating into something transcendent just sounds stupid, and watching Wayne fuck around on the most extravagant playground in the world, jettisoning down blood red slides cackling “soo woo!” while flashing his diamond-encrusted dentistry in sheer infatuation of self probably isn’t too appetizing. That’s the view from outside the gates, I would assume: a fool and his toys.

Which is fine and all, but, just—dude, the gate’s left ajar. I’m too young for the bank holdup/party that is the “Get Money” video but Weezy’s theme park is open to all ages; I’m wandering deliriously through, sipping Patron out of a Sprite bottle. I haven’t the faintest clue why, though, because if I am apprehended, I’m sure I’ll just get to fuck the cop or Weezy will fuck the cop or something else wonderful will occur. Here there is no good or bad. Here we are all Martians. All actions and motivations are reflected through the prism of Wayne’s perception, projected into a stunning spectrum of, fine, ugliness smeared liberally across the dome of the atmosphere like the outrageous mural of ink covering his body. We’re undoubtedly living on Lil Wayne’s planet, willingly or otherwise: hurricanes demolish cities, senseless wars persist, and, in good faith, someone somewhere is smiling. Tha Carter III is a thumbnail sketch of that incomprehensible breadth and dizzying complexity, pocket-sized but immense. Beautiful, too, yedig?