Features | Lists

By The Staff

20 :: Warpaint

The Fool

(Rough Trade)

That feeling you get in your stomach, the indefinable stirring as a strange weather system comes rolling in—it is exactly that internal change, paired with the deeply ominous and subtly agitated, which flutters seductively in the pit of Warpaint’s The Fool. For all its rich, tactile moments, it’s an album that’s unsettling to the core, that turns over constantly into more-nuanced sensations, never affording a single moment to feel stale.

The Fool is so thematically and sensationally nebulous that to tack the term “pop” onto it can feel pretty misleading. Yet every song has its catchiness, its deep-sinking hooks that suggest otherwise. Every song has its historical antecedent. Having undergone something like four years of seasoning, attentive editing, and masterful revision after revision after revision, the all-girl band from LA have accomplished an album that forks up a multi-dimensionality our minds really have to create room for. The Fool is a sprawling collection of lengthy tracks presented without remorse and without intermission.

The Fool isn’t just that. Also: vocals which exhibit all shades, from a touching, intimate delicacy, to creamy pleas, to spacey, soulful notes stretched out into full landscapes. Also: often pulled through a haze, over eked out guitar strums, or across a frisky pattering of snare and cymbal-lusty rhythm. Also: a sweet-and-sexy concoction that forms a long, long bridge connecting pop to psychedelia.

And The Fool does have pop songs. The beautiful “Undertow” sees Warpaint weaving their sound like textile or prescribing vitamins like they’re balancing humors: lyrics that are succinct, if coded; voices that drift in boldly, if etherized; and sweetness, even if it’s very often narrowed with jaded candor. The intimate, accessible “Baby,” with sparse guitar strums and unfiltered, candid vocals, mingles with the chilling sharper edge of a relationship’s ennui. The slow, accumulating swarm and panic of “Bees” builds suspense the vocals shake off midway only to watch it come back full-force and then unravel into different voices that are dreamier, gauzier, and more foreshadowing than the fabric panels in the music video for “Total Eclipse of the Heart.” An unexpected “Composure” channels the adolescent chanting of uncouth Brit girl-rock to bookend what appears to be Warpaint’s staple: the dreamy vocal aesthetic.

The Fool is an album that, with breathtaking maturity, embraces just how incisive, cruel, and horrific typically blunt emotions like boredom, ennui, and nostalgia can be. How sour and bitter the other side of adoration can turn. How even affection over time can just fucking…murder. It’s an album painted entirely in grays, but an album of constantly shifting shadows of aspects we thought were easy enough to understand in—well, pretty much every other album of pop songs.

Kaylen Hann

19 :: Gil Scott-Heron

I'm New Here

(XL)

Double-header of the year: I’m New Here and My Beautiful Dark Twisted Fantasy. A symbiosis has begun to develop between artists, between Gil Scott-Heron, the rap forefather and soul visionary of a “Revolution Will Not Be Televised” era and Kanye West, Lord of the Douchebags. Kanye samples Gil Scott on Late Registration (2005), Gil Scott samples Kanye’s “Flashing Lights” on I’m New Here, Kanye plays Gil Scott’s words from “Comment #1” wholesale on the closing track of his magnum opus, the climactic repetition of Gil Scott asking “who will survive in America?” becoming the most empathetic moment in Kanye’s entire oeuvre. These artists’ art is intently reflexive of self and of each other: the former sees the passion and excess of its youth, the latter sees the roots of its past and the dawning of its future. I’m New Here and MBDTF are two very different sides of one very singular coin, or perhaps it would be more accurate to say they’re at two different ends of one personal time spectrum. How telling is it that while Kanye uses Gil Scott’s words to voice poetically his own malcontent that Gil Scott turns to the words of indie-folk misanthrope Bill Callahan on his record’s title track? The bloodlines of art run deep, deeper than skin color, genre, or generation. Where MBDTF is almost ironically grandiose and maximalist in its struggle to assert identity over the trappings of a decadent culture, in making something beautifully prismatic out of one’s own brokenness, I’m New Here takes that same essence and ages it, withers it, distills and then abbreviates it into brief spoken-word pieces with hushed tones and minimal accompaniment. Welcome to Recession Music, Vol. 1. But despite the coldness and loneliness of I’m New Here, it is no less triumphant than its younger counterpart.

Gil Scott confronts the pall of death with both some toughness and some vulnerability—and more than a little wryness. Sonic centerpiece “New York is Killing Me” could nearly be blues parody with its “doctor, doctor” cries if not for the cutting-edge nature of its aesthetic; it sounds like TVOTR a few decades from now, everything unnecessary in their style stripped away and the bare core left croaking and clapping out grinning dread. Ever the progressive, Gil Scott, even at 61. But actual (and fantastic) songs like “New York is Killing Me,” “I’m New Here,” and “Me and the Devil” are in the minority of tracks, the majority consisting of musically-backed poems that as much as they are vignettes are also in turn the establishment of the record’s solipsism and elliptical syntax, finding vitality in the circularity in a way that seems wise beyond even Gil Scott’s ample years. “Turn around, turn around, turn around,” runs the titular hook, “and you may come full circle / and be new here again.” In fact, Gil Scott brings the whole album right back round, opening with “On Coming From a Broken Home (Part I)” and finishing with Part II as that same “Flashing Lights” music plays in the background, muffled, as if coming from a room over, those string swells brushing against peeling paint and plaster. In the intro Gil Scott tells of his childhood, the refrain always “and I came from a broken home,” a statement rooted in the loss of his grandmother Lily Scott, who cared for him as things were getting “patched” indefinitely at home until he became “the patch that held Lily Scott, and she held me.” Who knows in full what devastation the loss of his mother wreaked on Kanye’s psyche, but it could be that Gil Scott knows and knows where that journey leads, knows the answers to the hardest questions are only answers you come to feel within yourself. There is anguish in Gil Scott’s performance here but there is also acceptance of that anguish; it’s a tight-lipped peace that hums quietly in the depths of Gil Scott’s deep, deep voice. And there’s a directness in the ambling of his words—after an album of stark eloquence he concludes simply with “My life has been guided by women, but because of them, I am a man. God bless you, mama, and thank you.” Amen.

Chet Betz

18 :: Deerhunter

Halcyon Digest

(4AD)

Halcyon Digest is one of those rare albums that sounds instantly classic—as in instantly and believably old. Bradford Cox and Co. have put together a collection of songs vibrant and catchy enough to be radio-friendly (at least back when that term meant something in the rock genre) but also complex and occasionally challenging. Perhaps more contained than their previous work, Halcyon Digest has a soft glow about it; memorable but gentle, it creeps up and sits in the back of your mind, on the tip of your tongue. These guys aren’t new to the game, nor are they kids anymore, and so their songs grapple with issues like growing up, remembering, regretting, and grieving (the latter especially apparent on album closer “He Would Have Laughed,” written for the late Jay Reatard).

The band mostly trades here in vintage-sounding garage- and brit-pop, particularly engaging on standouts “Desire Lines,” “Memory Boy,” and “Helicopter.” A feeling of immediacy characteristic of Deerhunter, especially in Cox’ s abstract and off-the-cuff lyrical style, fragments the songs and sometimes pushes them in circles, but is usually just trying to combat the album’s ever-present themes of aging and mortality. On “Basement Scene,” Cox waffles between “I don’t wanna get old” and “I wanna get old”; “He Would Have Laughed” and the Lockett Pundt-penned “Desire Lines” also deal in equal measure with losing the passion of youth. In “Sailing,” Cox whisper-sings over a tentative guitar about being lost at sea, one of the album’s most piercing metaphors. “Only fear / Can make you feel lonely out here,” he breathes, “You learn to accept / Whatever you can get.”

Deerhunter doesn’t let the album’s heavy themes stifle its charm or sense of adventure. Which is wise: this is surprising, affecting, and righteously entertaining indie rock. And it’s been looping in my head for seemingly forever. Like maturity or death, Halcyon Digest is its best when you’re not resisting it.

Maura McAndrew

17 :: Future Islands

In Evening Air

(Thrill Jockey)

I’d be missing something important if I didn’t mention up front that the Future Islands are the hardest working band this side of Ted Leo and the Pharmacists. At one point this year I heard about a European tour during which they played 34 out of 36 days. Their American tour was apparently even crazier. This seems worth mentioning because the work ethic, that mixture of unbent obsession and perfectionism, is apparent across In Evening Air: nine songs of finely-honed electro pop, pulsating with sincerity at its vulnerable core. A broken-hearted armada trimmed to its most essential and deadliest weapons. Every last song vital to the album’s stubborn affectation, its in-turns angry and melancholy drive.

And such a balanced and economical record, too. Sam Herring’s vocals, both his tone and lyrics, are the emotional nucleus of the music, but the songs—usually bass, a drum machine, and some synths—give Herring all the room he needs to stretch out, to explore the spaces in their formula. The album seems to be about breakups and memory, but the gravelly modulations in his performance become stories and subtexts in themselves—evocative, suggestive, speculative, lending inarticulate specificities to what are, basically, universal sentiments.

Opener “Walking Through That Door” is pyrrhic and haunting, perfect groundwork for the exposed “Tin Man” and glossy “Vireo’s Eye.” Herring vamps and growls while the root-note bass lines are painted in New Wave dashes. It’s infectious, vulnerable stuff, both ineffable pop and yet too stark and sleek to be only that. Future Islands leverage what we know works while trimming the fat from our meandering desires, leaving one of the most straightforwardly satisfying listens of the year.

Conrad Amenta

16 :: Yellow Swans

Going Places

(Type)

There’s an image I store in my head for when I listen to “Limited Space,” the remarkable centerpiece to Yellow Swans’ ambient noise masterpiece and last record before an unfortunate split: an inexorably slow sweep over a cityscape at night (possibly Tokyo, because it’s not built upward like an American city, but instead consists of unbelievable density sprawling out over the horizon); lights like anxious, buzzing jewels in cool metal housings; and from a high aspect the barely definable silhouette of buildings layered across one another. I can’t help but feel that this image conveys the scale this type of music evokes. This music is very large, terribly beautiful the way a slumbering monstrosity possesses terrible beauty—a battleship, a storm cloud, a demolition. A chime rings false as noise builds and a guitar beats out its rhythmic, one-note pattern, but when the three-note guitar drone comes in at the end of the song, and all the pretense of support is dropped away, it’s a hideous, leviathan moment of unadulterated and utterly convincing melodrama. The patient build, the pacing of the thing, makes real the sound of heavy distortion clawing at the insides of your head. It’s also a moment announcing that ambient no longer distinguishes itself by its absence of dynamics.

Yellow Swans locate themselves in that same extremely relevant vein of dirty ambient music to have leapt, startlingly, out from the fringes of experimental noise and into the modern cultural atmosphere. They can realistically be included when speaking about how artists like Keith Fullerton Whitman, William Basinski, Tim Hecker, and Ben Frost have captured that post-Millennial dread and animal alienation underneath the horrors of our last decade. It’s not nuanced, nor is it designed to be. Music like Yellow Swans’ is guttural at times, but immediate. Tumbling feedback and cadenced noise is nothing new, but this record’s concision and precision, the urgency with which it conveys an environment of building anxiety, is absolutely contemporary.

Conrad Amenta

15 :: Grimes

Geidi Primes / Halfaxa

(Arbutus)

Francios Truffaut once wrote that “there are films that one admires but which are discouraging: what is the point of continuing after them, etc. Those are not the best, because the best give the impression of opening doors and also of the cinema beginning, or beginning anew, with them.” If the same basic principal applies to music—and surely it does: consider those mainstream rappers now tasked with following Kanye’s bar-raising act—then Geidi Primes and Halfaxa, the stunning pair of debut records by Montreal’s Grimes, are resolutely the latter. These albums bear the mark not of career-defining masterpieces—the greatness coveted and improbably grasped by Yeezy last month—but of sudden, prodigious genius; springing up seemingly out of nowhere earlier this year, the discovery of Claire Boucher was less a nice surprise than an outright revelation. Just how important a discovery that was remains unclear, because even more than great albums in and of themselves Geidi Primes and Halfaxa are indicators of Boucher’s potential for greatness to come. So fuck it, I’ll make the sweeping claim now, gratuitous hyperbole and all: Geidi Primes and Halfaxa herald the arrival of a major talent and an important new voice.

Given the rate at which trendy new microgenres explode onto our taste-making radar (as well as the swiftness with which they inevitably recede from view and fade from memory), bold declarations of this or that unknown artist’s undeniable cultural significance might seem a little hasty, and I understand that it’s best to err on the side of skepticism. But everything about Grimes stands apart. It’s not that this music sounds so radically “different” or quirky or novel; it’s more that Boucher herself seems to be working from within a different headspace, approaching music a different way. In fact, the only contemporary musician to whom I think Boucher could accurately be compared is Girl Talk: both Boucher and Greg Gillis are experienced listeners but amateur creators, and though Grimes is a project far more sophisticated and accomplished in the application of its creator’s talents, both opt to reject the standard practices (and forms, styles, conventions) of the musicians they want to emulate in favor of forging their own paths from scratch.

I could argue for Boucher’s induction into the cultural canon till I’m blue in the face, but the crucial import of all this effusive praise should merely be that Geidi Primes and Halfaxa are, simply and without claims to lifetime relevance, wonderful albums. I love this music as a revelation, of the (possible) inception of an exciting new movement, but I love them also for moments of simple beauty: I love “Rosa,” which takes pop music and whittles it down until only the barest elements persist; I love “Devon” because it buries its impossibly infectious “la-di-da” hook way in the back, demanding that you wait nearly four minutes for its payoff. I just love both of these albums, wholly and thoroughly, and I can’t wait for whatever doors Grimes opens next.

Calum Marsh

14 :: Sharon Van Etten

epic

(Ba Da Bing)

Sharon Van Etten’s epic is a collection of seven masterfully sequenced and arranged songs, showcasing different aspects of the singer-songwriter’s talent within its 30 minutes in a way that her debut, Because I Was In Love (2009), didn’t in eleven songs and 40 minutes. As a product from start to finish, it is a singularly swift and devastating thing, proof that Van Etten is a far more vital songwriter than I once gave her credit for being, and the sound of potential I once couldn’t hear at all being realized in real-time.

On epic, Sharon Van Etten maintains her debut’s sense of intimacy—she still deals mostly in I and You statements and fixates on friendships and failed romantic relationships—but brings in a full band, which allows for textures and sounds that once seemed outside her grasp. Opener “A Crime” is the only song to feature just guitar and voice, but it’s hardly an attempt to hold back; it lunges for the throat within seconds and never lets up. From that point on, epic is the sound of a singer expanding her palette to marvelous effect: “Save Yourself” uses aching pedal steel and Van Etten singing harmony against herself; “Don’t Do It” builds to a huge, explosive finish almost through percussion and howling vocals alone; and the aching country within “One Day,” the droning “D sharp G,” and the return to sparseness on the harmonium-driven “Love More” do wonders for the singer, who sounds utterly in command of her voice.

More than anything else, though, epic is a triumph of songwriting. Van Etten treads territory well-explored in folk and pop, and makes it not just her own but utterly vital. These songs have stunning melodies, lyrics that connect swiftly and efficiently, and a sense of propulsion (only partially a consequence of their percussion) that makes them hit almost immediately. When performed live (and stripped of all ornamentation beyond bass, guitar, drums, and voice), they didn’t just hold up; they sounded better. In a very short period of time, Van Etten has revealed herself as a songwriter and a performer to be ignored at one’s own peril, and given the staggering growth that happened in one year and between two albums, I personally couldn’t be more excited to see where she goes next.

Andrew Hall

13 :: Emeralds

Does It Look Like I'm Here?

(Editions Mego)

Does it look like I’m here? This is a wordless work, so the question just goes to town on my brain during the hour this record inhabits my headspace. After spending a considerable amount of 2010 trying to muster a substantive response: well, yes and no. Emeralds’ brilliance is here like a season, like an abandoned industrial park, like breath. Listening to Here is not the image you see when you look in the mirror, it is the moment when you turn slightly to the right and see the outline of a dead loved one’s cheekbones, having never really noticed those cheekbones before; cheekbones haunt the bathroom. Perhaps that’s too specific: Here happens between walking and falling. Your shoe slips, you feel an illusion of weightlessness, twenty things happen in your head, and you’re on your ass. Here takes that dense hunk of twenty things and rolls them out like continent-sized pizza dough.

Does it even look like I’m here? I imagine the question pouring out of every inanimate object. The album cover shows an old Magnavox on a couch—blank, white, glowing—staring out at me with fuzzy drool collecting at its corners. A tar-like gunk drips from somewhere inside me, which now feels like it’s outside me. I begin to understand what webcam strippers must feel like. I would go home were I not already standing in my kitchen. Or in my bathroom. This albums stirs within me sensations that straddle the line between the familiar and the strange. Only Emeralds could stretch the uncanny into a seven and a half minute title track.

Does it look like I’m here? I’m not sure. I can feel you all around me. I’m like a blind bird flying through a fireworks display: the sound and heat are enough for me to sense that something spectacular is occurring. “Now You See Me.” Yeah, but not literally. Emeralds are on to something with these titles. Maybe asking completely irrelevant questions is the doorway to profundity. What Happened (2009) dares you to summarize its immensity. Here asks you if you’re stupid enough not to trust your eyes.

Does It Look Like I’m Here? No, but I know you are.

Colin McGowan

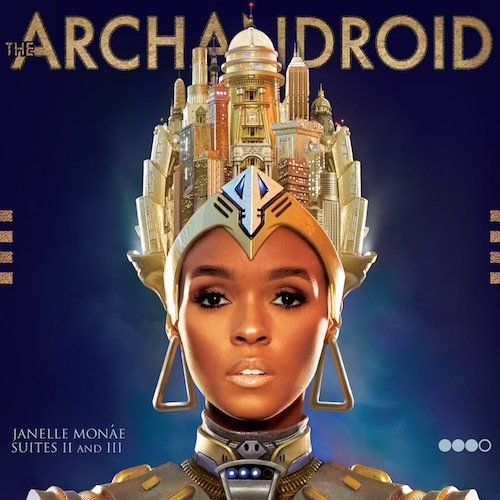

12 :: Janelle Monáe

The ArchAndroid

(Bad Boy/Wondaland Arts Society)

“You can pull the trigger or you build you an ark.” Guess which one Janelle Monáe chose? Playing through every genre like it would die out if she ever stopped, The ArchAndroid is the soundtrack to a sci-fi epic that takes place in the not-too-distant future where the world’s external hard drives are threatened by a giant magnet constructed on Mars by the FTAA, and the world’s surviving righteous musicians have to ride the ark (Parliament’s mothership) to a safe galaxy.

This has been called Broadway music, which I guess makes sense insofar as where else would you find another scenario where music was the solution for (and potentially the cause of) every problem? She opens the album with the ultimatum “dance or die” as if those were the only two options left. She sings a song about keeping things close to your chest (“Tightrope”) with a stock market/Macbook-referencing verse by Big Boi, and it never seems out of place next to “Valley of the Dolls”-esque soft rock (“Sir Greendown”), Prince-shooting-sperm-guitar solos (“Mushrooms & Roses”), torch-song R&B (“Locked Inside”), psychobilly (“Come Alive”), Fairport Convention/Tolkien-folk (“57821”), and Rat-Pack lounge by way of 20th century neo-classical composition (“BaBopByeYa”). Even the Of Montreal song is alright if you picture Kevin Barnes shoveling elephant shit on the ark while Monáe changes into the final gown (tuxedo?) for the climactic celebration of cosmic magnanimity on “Wondaland.”

I never took this to be particularly tongue-in-cheek. The album is simultaneously a symptom and treatment for iPod shuffling. It’s like hip-hop with each sample stretched out into its own self-contained unit: there’s no real coherence or narrative, but each moment feels right on its own terms. On the cover, she bears the weight of a ridiculous futuristic metropolis on her head but she looks as devastatingly intense as she does in the Sinead O’Connor-referencing music video for “Cold War,” as if the fact that the very same battles are played out across centuries adds that much more urgency to it. Finally, this album is a manifesto, with only one bullet point: stay afloat.

Joel Elliott

11 :: Menomena

Mines

(Barsuk)

At the beginning of the sad-sack triptych that composed the back end of Menomena’s previous record, 2007’s Friend and Foe, Brent Knopf emitted a wailing lament—“Oh, to be a machine / Oh, to be wanted, to be useful”—and some imperceptible shift occurred. Dom and Calum discussed extensively the chasm between how Menomena packages its message and how jet-black its message can actually be, but what I hear on Mines is a group of dudes barely even trying to be happy. While Menomena might have, in the past, masked their discontent with nervous energy, crying to themselves in a treehouse made of fluorescent construction paper, this is just a bunch of sobbing in a dark hotel room with the blinds half-open.

When the pyrotechnics of “TAOS” fizzle, we’re left with a lot of weary bleakness; as is Menomena’s wont, it’s meticulous and beautiful. These compositions allow the unimpeded sadness of the vocals to wash over them like torrential rains over landforms. Because Danny Seim just sounds so naked and despairing on “Dirty Cartoons”—it’s unblinkingly intimate and even a little disgusting—like he’s letting us into the first 60 seconds of a hangover that’s just going to suhhhhhck. Because the way in which the bass line on “Tithe” underscores the unfulfilled desire washing over Danny Seim, washing him out, feels unequivocally correct. Because the bottomless pianos on “INTIL” clasp and nearly extinguish Knopf, just as he seems to fear his empty couch might. No matter how much everyone loves you at the party, you eventually have to come home to the empty home you’ve built and emptied.

In its most powerful moments, Mines is devastating. This is also, probably, as confessional as Menomena get, not because their outlook has taken a turn for the worse, but because their kinetic energy has dissipated. In making explicit what they only once intuited, they allow the listener to experience fully just the type of shit with which they’re dealing. In turn, their music burrows further into the listener’s chest and plants a simple, ineffable sadness. Oh, to be wanted, to be useful.