Features | Lists

By The Staff

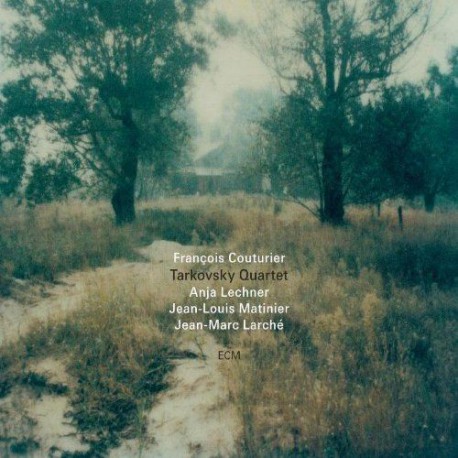

50 :: François Couturier

Tarkovsky Quartet

(ECM)

Funny that this should be at the top of our list. There’s a lot of great rap, indie rock, and electronic music in the next 49 slots; Tarkovsky Quartet has nothing to do with any of that. The album hovers somewhere in the interstice between contemporary classical music and jazz: it has the dusky ambiance and occasional improvisatory flights of the latter, but its approach and compositional style are closer to the evocative pointillism of post-serialist composers like Anton Webern and Olivier Messiaen. It’s also the third and final entry in a series of albums inspired by the great Russian filmmaker; like much of Tarkovsky’s work, this is art that unfolds slowly and deliberately, engaging the listener on a highly cerebral level, and it doesn’t give up its rewards easily.

But if you can get past the lack of a hot single, Tarkovsky Quartet is also a deeply affecting and haunting hour of music. Tracks like “L’Apocalypse” and “Sardor” are masterfully executed exhibits of tonal chaos, the musicians stringing together jarring bursts of dissonance into colorful polyrhythms that are as unsettling as they are captivating. And the slower pieces have a certain mournful aura, as if they were different formulations of the same commemoration to a timeless absence. Like that of Tarkovsky and Messiaen before him, Couturier’s art finds in the human reaction to this perennial emptiness something vital—a kind of nostalgia for the end of time, with all the paradox that implies. Apocalypse, yes, but as a reality immanent to our present existence—and as the truth of those arts that are sculpted in time.

Brent Ables

49 :: Bill Callahan

Apocalypse

(Drag City)

It’s pretty sickening, actually, the way Bill Callahan seems to do no wrong. The man can age gracefully, can wear a suit, can command an audience, can attract all the hottest indie rock chanteuses. The only thing he can’t do, it seems, is write a bad record.

But even for Bill Callahan, Apocalypse is an impressive achievement: a lonely, gorgeous record like a breath of crisp mountain air. Though he retains his trademark wit, this is one of Callahan’s darker efforts—beneath a layer of open-range nature metaphors, Apocalypse has a deep well of sadness at its heart. The opening duo of “Drover” and “Baby’s Breath” in particular can feel like being alone at the end of the world, but Callahan’s deep, engaging voice is always there to anchor it, drawing the listener close to him even as he seems to grow more detached; it’s impossible to miss the heartache in lines like “How can I run with losing anything? / How can I run without becoming lean?” These questions are never quite answered, and Callahan sustains an uneasy, unsatisfactory feeling throughout. From the slick, queasy anthem “America!”, to the breathtaking “Riding for the Feeling” (which seems to take forever to reach its swooning chorus), to the contemplative finale “One Fine Morning,” he seems to find temporary solace…but never redemption. Though Apocalypse abounds with what Callahan terms “a country kind of silence,” it’s the ugliness that flares up beneath the surface, growing ever louder—maybe not in a way we can hear, but one we can feel.

Maura McAndrew

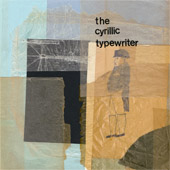

48 :: Cyrillic Typewriter

The Cyrillic Typewriter

(JAZ Records)

It’s hard to spin “makes great background music” into much of a compliment. Nevertheless, I’m not being backhanded when I say that the Cyrillic Typewriter’s self-titled debut is possibly this year’s great album to throw on at low-key gatherings, settling into cracks in the conversation, its fastidiously orchestrated beauty scoring pulls from a beer bottle.

Because while 2011 was a great year for headphones-only albums, aren’t communal living-room gatherings one of the altars of musical communion? So many of the albums I’ve loved this year have led to stilted moments when put over the speakers. Shabazz Palaces’ keening notes propel philosophical banter into existential crises. PJ Harvey, though pretty, bursts in on political conversations with awkward questions (“What if I take my problem to the United Nations?”). And Colin Stetson, though he made my favorite album this year, can really fuck up a party. Comparatively, the Cyrillic Typewriter makes a pretty excellent case for the idea that our attention should be willfully given, rather than seized. Jason Zumpano’s music is easy to listen to, but far from easy listening: a folk-tinged take on minimalism that incorporates Steve Reich-ian guitar and piano lines; vocal harmonies that are half Elephant 6, half middle ages; a string section with a rare gift for restraint; and the seamless patchworking of a master compositor. This is an album that, even when put on to pad the room, has never failed to elicit the question, “Who is this, anyway?”

The answer: one of Canadian music’s most overlooked players. Zumpano seems to make flying under the radar a way of life. Despite having been signed to Sub Pop (with his power-pop group called, appropriately, Zumpano), working with some of the most high-profile artists in Canadian indie rock (Carl Newman, Dan Bejar), and most importantly, writing great music, no one really knows who he is. I needed the Internet to tell me that he lives in the same city I do. Perhaps this is due in part to the kind of reception such subtle albums often receive. The Cyrillic Typewriter isn’t going to melt our eyes out of our heads or fuel anecdotes of dance mania. It’s the kind of thing most of us will unthinkingly catalog as pleasantly quirky, then move on. Yet “quirky” is so often a word we turn to when music doesn’t try to make us feel explicitly sad or romantic or pissed off. The Cyrillic Typewriter certainly doesn’t cater to such block-headed emotions, instead prodding in the dusty crannies of musical experience, exploring whimsy and nostalgia and singular concentration. In The Cyrillic Typewriter, Jason Zumpano has zeroed in on his targets with laser intensity that will bore through even the most involved repartee, coloring the listener’s experience without explicitly telling him what to feel. And so it doesn’t matter if no one actually knows who Jason Zumpano is, or what he’s done. Put this on over beer. Someone will ask.

Jessica Faulds

47 :: Gil Scott-Heron & Jamie xx

We're New Here

(XL)

It’s strange listening to Gil Scott-Heron’s voluminous ’70s output from the vantage point of his final works, where not a half hour of covers and sound bites have now been coaxed into two albums. Drugs, HIV, and time wore at his verbosity and self-righteousness, and it seems as if he could only bring himself to communicate in short bursts (much like the samples that have immortalized him: “Who will survive in America?”). That, combined with the care and respect others have taken in selecting music to accompany his words, makes his older material seem blustery and poorly thought through. Perfunctory funk and dated politics given too much free rein by a flush music industry and myriad causes looking for a figurehead.

We’re New Here takes the already careful curation of I’m New Here to Jamie xx’s airy frontiers: full of silence, low tones, and a sure grip on the pitch and volume dials. The title track drifts even further from its origins as an acoustic Bill Callahan song, beginning in the ether and building into pitched-shifted urgency. Scott-Heron’s defiant, wistful musings are treated as a showcase, the empty space full of tiny jokes (like ’70s bongos over a defense of youthful mistakes) and artful dubstep, building real tension and narrative. Jamie xx has found a middle way, not as sleepy as James Blake or as hectically tuneless as his more blithe peers, of making crowd pleasing electronic music with an eye on the details. It’s perfect for the material at hand, just as danceable as Scott-Heron used to be, but with a cold objectivity suiting more candid reflections.

Drake’s appropriation of “I’ll Take Care Of You” already has launched the record into some kind of iconic status, and the zeitgeist hovers quietly over every song, the idea of the right music being made at exactly the right time. One artist dying and another one being born, the vapor trail of Scott-Heron’s excess in the sure hands of Jamie xx’s tastefulness. It’s a random, fortuitous record, two polar opposites stumbling into each others’ orbit and making some of the best music of their lives.

Chris Molnar

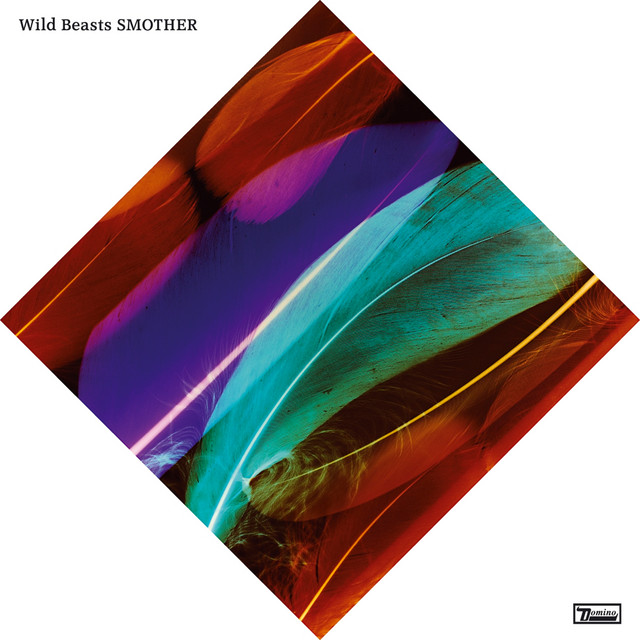

46 :: Wild Beasts

Smother

(Domino)

Wild Beasts frontman Hayden Thorpe represents the new gold standard in the latest class of British waifs. He looks like Elijah Wood; he sounds like the forsaken son of Antony Hegarty; and were he to vanish off the face of the earth after releasing Smother, Wild Beasts’ third album, he would assure himself a spot in the Tortured Soul Hall of Fame alongside Ian Curtis and Richey Edwards. Die young and stay beautiful, right?

Though absolutely precious album opener “Lion’s Share”—a melodramatic slice of piano cabaret in which Thorpe promises to “take you in my mouth like a lion takes his game”—leaves an indelible first impression, the remainder of Smother wallows in a pretty much uniform malaise. No immediately catchy choruses and no solos to speak of, it initially sounds like little more than a gloomy 40-minute soundtrack ideal for slitting British wrists.

But few records in recent memory work their way under the skin like Smother can. It’s singular, sometimes uncomfortable, often entirely obsessed with the opposite sex and the shortcomings of its protagonists. Hayden Thorpe and co-lead vocalist Tom Fleming (think Peter Gabriel-ish) don’t so much sing as whisper, and Wild Beasts’ sound has been pared down over three albums from theatrical to unnervingly bare, relying solely on spare electronic beats and ambient dread, sometimes resembling a typical Noah “40” Shebib track. Lead single “Albatross,” all striking ballad and ballet-themed video, is even better within the context of the whole deeply mysterious album. Smother is marvelously coherent, and only after repeated listens does it truly emerge a subtle, sensual piece of work that in its finest moments recalls the minimalism of latter-day Talk Talk. I’m having trouble thinking of higher praise.

David M. Goldstein

45 :: Andy Stott

Passed Me By / We Stay Together

(Modern Love)

In two EPs, Andy Stott has achieved a new title for himself: King of Apocalyptic Techno. Anyone not into the rigid sound of dance music (you like your parties through walls, or on opiates, for example) can find a hook in Stott’s output, which this year drowned the nightclub experience as a whole in layers of world-destroying fuzz. May’s Passed Me By was a rebirth for the former 12” whizzkid—it was like he overshot Fabric and landed nearby in a swamp. Analogue crinkles at the opening track; the gleaming distortion of “North to South”…this was something that crossed ambient techno with anthropology, an EP that delved deep into the mind of the producer while expanding the producer’s external landscape as thoroughly. Highlights include “Execution” (heavy breathing over woodland rituals) and “New Ground” (a Motown tune hammered by a blacksmith): clearly Andy Stott had been having dreams of Armageddon, and was worried any stragglers in the fuming landscape would require a beat for their weekends.

If Passed Me By was a taste of the future, We Stay Together fed it to you with a ladle. Everything about it is darker, angrier, rougher than its predecessor; any hope of a weekend well down the toilet. This is not, admittedly, normal output for a Manchester techno DJ—they shouldn’t be allowed access to crypts and cymbals. Tracks like “Cracked” are more the cabalistic ideas of Demdike Stare than Stott’s own work, taking Turkish folk music and feeding it to beetles. Moments of light still grace the EP—the house swell/chewed vocals of “Posers,” or the out-of-body experience on “Submission”—but for the most part We Stay Together sucks the listener deep down a mineshaft, only to have one encounter electrical fields, sandstorms, and voodoo in the basement of the world.

And this time next year? Who knows where Andy Stott’s Brundlefly evolution will take him. Hopefully not to a childrens’ party.

George Bass

44 :: Moonface

Organ Music Not Vibraphone Like I'd Hoped

(Jagjaguwar)

Memory has many waiting rooms, and Organ Music Not Vibraphone Like I’d Hoped is when Spencer Krug cracks open the door to his. We cross—one dark room after the other—without re-crossing: no circling back, no labyrinthine tours, only a single yarn of dancing arpeggios we can trace back to the album’s first seconds.

Think back: tangled, wrought, and clogged as they were with imagery, always coded with a staggering arsenal of myths, metaphor, and story-twisted-around-story—folded a thousand times over in exponential intricacy—Spencer Krug’s songs, in Wolf Parade, in Sunset Rubdown, and now in Moonface, have never hesitated to spill their (and his) guts in eight-minute profusions, in twenty-minute purge-sprees, or to let a lyrical vein course to the point of symbolic superfluity. Yet, Organ Music, certainly sparse in comparison to everything he’s done (‘cept maybe the last Moonface record), is finally a Krug album created in an absence of such typical entanglements and self-interruptions. Maybe this is what intimacy from Spencer Krug sounds like.

As in: immense, simple landscapes with a mammoth tenderness and small thoughts issued in such quietness that they feel mountain-big. It isn’t an easy thing to recognize, particularly from artists like Krug—because: there aren’t artists like Krug. He’s just never going to be that guy busting out an acoustic guitar. Rather, he’s that guy who plays marimbas and vibraphones, or regrettably organs instead of vibraphones, instruments that maybe fly under our Intimacy Radar with their hefty weight of novelty. But they’re unique to him in the way they play, fitting with his voice; they resonate like woodwinds, these instruments Krug’s chosen for his solo effort; they seem to have their own set of vocal chords, stowed, like Krug’s, in some internal cavern.

It’s new closeness for Krug, this record, and not because Krug’s shy about doing Krug, but because the album’s recordings seem to occur in such a space of sanctuary. Organ Music is like a quiet invitation to an even quieter conversation he’s having with himself, a reflection or a replaying of shit in his head. “But your face looks like a statue in the dark / Like a candle that is held up to a mirror,” he recites, which could be something he’s singing to his own reflection. Songs like “Fast Peter” are colored not by the story but by his reactions; his muted awe at Peter pulling up roots and moving for his long-distance lover are littered with open meditations. “Who even does that any more?” His voice is hushed, like it’s touching at a bruise, while the double-manual flies off in mangled, improvisational runs and naïve, chintzy flourishes underscore declarations—“She’s the one / The one that he thinks of when he thinks of love”—with a twinge of cynicism.

Organ Music Not Vibraphone Like I’d Hoped is Spencer Krug taking for himself (or for us) a King Canute moment: setting his epic, songwriting throne before the ocean and saying, “See, watch while I command the waves to roll back.” In turn, soaking him with fallibility, they don’t. For once, it’s easy to see the wirings of Krug’s songwriting, to witness those guts of his craft unfurled and stretched out, miles and miles of fallen telephone-wires, or blank bar after blank bar of sheet music. For once, we can follow the lines, the yarn, from beginning to end. Discernible? Maybe; at least in the deconstructing of his own mythical image. Accessible? No, of course not, but, like any Krug record, it’s as good an introduction as any to the guy. Perhaps one day it’ll prove to be the best. At least until the next one.

Kaylen Hann

43 :: Miracle Fortress

Was I the Wave?

(Secret City)

Even without its aqua-drenched cover-art or suggestive title, Was I the Wave? feels like a steep plunge. We linger briefly on the coastline of “Awe,” admiring its ripples, but once the funky bass and thick, synth-y undertow of “Tracers” rises up, we’re swallowed into a forty-minute surge that consistently feels closer to twenty, where Miracle Fortress, aka Graham Van Pelt, commands addictive electro-pop choruses and understated sound-experiments at whim. They organize like the invisible gears of a tide, rolling back in out-of-focus segues one minute before crashing upon our laps as full-blown rave-ups the next. Over its peaks, Was I the Wave? escapes its colder currents and takes in some vitamin D, with “Everything Works” and “Miscalculations” basking in some upbeat, confessional pop hooks. By the time “Until” flutters to a close on sanguine guitar lines, we’re marooned somewhere between Van Pelt’s dancefloor and daydreams, trying to regulate our temperatures.

Watery metaphors aside, the fresh tones of Miracle Fortress’ sophomore full-length were helped by circumstantial elements—namely a lot of rain. Released amid a torrential downpour that hovered over Van Pelt’s Montreal on April 25th, Was I the Wave? perfectly sums up the reinvigorating promise of spring; when April’s thaw uncovers matted greenery we nearly forgot and the desire to blare electro-pop anthems from an open-window overwhelms. This record can cure the woes of any climate.

Ryan Pratt

42 :: 13 & God

Own Your Ghost

(anticon.)

Amidst the quadruple-time flows and dizzying rap-rock-electro-pop hybridizations it can be easy to miss one of Own Your Ghost’s key lines. At the climax of early highlight “Death Major,” an echoing plea of “All one wants is to be missed” can be heard wafting overhead. On an album so preternaturally concerned with death and aging—besides “Death Major” we have such suggestively morbid titles as “Death Minor,” “Old Age,” “Unyoung,” and “Sure as Debt” (as in, “Sure as debt, dust collects”)—the unassuming lyric gathers an unusually tragic weight. From any artist such declarations would likely sting, but coming from 13 & God—once thought to be a one-time mid-aughts collaboration between anticon mainstays Themselves and German electronic vets the Notwist, and on their unexpected return album at that—it plays like vital disclosure from a collective determined to persevere as the indie landscape continues to shift ignorantly alongside their own restless maturation.

The music itself—a near perfect composite of the Notwist’s electro-acoustic productions and Doseone and Jel’s avant-rap experimentation with both Themselves and Subtle—functions hardly as backdrop, instead texturing a handful of Marcus Acher’s most aching choruses since Neon Golden (2002) while engaging in full-tilt tussle with Doseone’s swerving, elusive narrative yarns. The details are typically difficult to parse—“So swung low in the clutch shot of night club light flow / Hence, it sent spent bent to the light hell of pop absence,” Dose somehow spits nonchalantly on “Et Tu”—but the gravity of the compositions in conjunction with the lyrical tone of the voices, frequently deployed in unison, facilitate an acutely emotional form of immersion. And although some of the concrete imagery that does emerge—“You can’t take the ‘eat’ out of the death / Oh no, that lettering set as a picture,” or, more nakedly, “Old age, old age / Anything but you”—may function solely to render the listening experience even more uncomfortably tense, it’s obvious that these are artists as resigned to the inevitabilities of time as they are dedicated to their pursuit of perfection-through-creation. Then again, maybe all this macabre insight is appropriate, as you’ll likely carry this music to your grave.

Jordan Cronk

41 :: The Men

Leave Home

(Sacred Bones)

The Men earned their stripes in 2011 by doing little more than living up to the names and titles they placed in front of themselves. They peddled their symbology in broad pitches—How is masculinity defined by a violent, reckless band called the Men? What does it mean to Leave Home when your “home” is Brooklyn, a symbol for musical variety, saturation, and success in its own right? Is it OK to steal so many signifiers from so many other important regional bands?—mainlining their sound with a homogenous mayonnaise of caloric sonic detritus, and somewhere, sometime in the dead of summer spewed up the fast food equivalent of a noise record: Leave Home, 2011’s righteous pile of steaming zeitgeist-chum.

Which is exactly why it rules so fucking hard. Its chum-ness drips with imprecision and waste; its noisiness with a callous disregard for, well, everything. Its regionalism just squats there, in front of your speakers, complaining about nothing in particular but sometimes grinning as it peers up at you, all “Look what I just did,” like a dog about to get hit with a newspaper or a fat toddler with old-soul eyes. It is, exactly, unnerving—if you like that sort of thing. Opener “If You Leave…,” in the band’s defining and introductory moment, drizzles to life with the ashy foreboding of a Pompeii pre-obliterate-all-you-know-and-love. Which it then does, nothing spared. Think that shitty The Road movie adaptation, but directed by that shitty Michael Bay fellow—or think nothing (as in: what’s left; what’s left of the lyrics after they’re churned through the songs’ teeth, just the word “nothing” and coughing) and simply billet into the song’s jarring pace, holing up there to weather the nuclear winter. Not that “If You Leave…” is a song so much as it is a setpiece of fevered guitars and dry glossolalia, a thoughtless dramatization of desperate, harrowing flight, but if Michael Bay can pretend present-day Detroit is a post-alien-Apocalypse Chicago, then we might as well be free to define a song however we want given the shifting standards of taste we’ve got going for us lately.

So anyway: run. Dodge the uprooted storm of shrapnel and chthonic feces, thunking against one’s ecstatic escape, raining over one’s sprinting path away from not just home, but manliness and womanliness and sexiness and health and completion and everything else the feels totally safe. And all the while, if you’re going to hug one LP to your chest? If you’re going to grab one piece of music to carry with you into a new age of survival, through the wreckage of whatever Leave Home guarantees is getting wrecked, which is probably everything, because have you looked outside lately? If there’s one thing of wonderful sound to canonize in the coming cataloguing of humanity’s remnants? It probably won’t be Leave Home. And the Men know this. They’re cool with it; they do not, as certain other staples in the popular consciousness have assured us of their own art, care. This is manliness at the end of 2011, I suppose. That it’s an utter fucking shitstorm feels so right.