Features | Lists

By The Staff

30 :: Solange

True EP

(Terrible)

I’d compare it to the Big Bang if it weren’t so subtle. It just sort of starts: a drum loop. And it loops; that’s what drum loops do, right, but this one is monomaniacal in its willingness to loop. The drums have got this smart, syncopated found sound. You think, maybe, of This Is Not a Test! (2003)-era Timbaland—one of that dude’s best looks, one he discarded a bit too soon. These spare, smart drums, looped ad infinitum, will be a constant on this album; they’ll drop out in key moments, but almost every track begins and ends on this foundation. So then (we’re still talking about how the album starts) moody Drive-wave synths show up, neon and lonely. A bass line runs up in, a little effervescent burble thing. The track appears to be complete.

It’s a minute into the album—it is, yes, roughly 3% complete at this point—before Solange shows up. She sounds kind of sad. She will sound this way occasionally on the album, in addition to sounding occasionally pissed off. She sounds human, which is really refreshing. (B never sounds human.) Solange is a likable presence throughout the record; she speaks to us with a distinct lack of vocal histrionics, peppering her lyrics with moments of sly wit, and with a keen, almost Badu-esque reverence for Dev Hynes’ production. She doesn’t compete with these synth-pop marvels, nor is she overshadowed by them. She just slips into the pocket on each one, one after the other, in dazzling seven-part progression.

But anyway, it’s all there in that first minute. The album will change shapes, from the Maxinquaye (1995) rap of “Nothing Ever Seems to Fucking Work” to the sprightly Prince slink of “Don’t Let Me Down,” but it will always be the same: those drums, that tone, and the character of Solange, cool as ever but suffused with a new, easy confidence. Like the album cover, or the album title, the aesthetic is absolute. I guess she’s calling this an EP, but I haven’t thought of it that way. I look at brevity as an occasional necessity for an R&B artist—_What’s Going On_ (1971) is 35 minutes. There is nothing, after all, more holy in R&B than sequencing, and you absolutely cannot fuck anything up. It’s why Channel Orange, with its scattering of unfinished sketches and its half-baked narrative, can only be defined by its best moments and its context. It’s why, despite a lot of loverman posturing, the whiplash production choices on Kaleidoscope Dream and Looking 4 Myself render them at best pop. And it’s why, despite the fact that it cribs from the past four decades of pop production and sounds like it was transmitted to us from a Beijing discotheque in 2015, True is the best and, yes, truest R&B album of the year, goddammit. Who cares if it’s short? It’s whole.

► “Losing You”

► “Lovers in the Parking Lot”

Clayton Purdom

29 :: Mount Eerie

Clear Moon / Ocean Roar

(P.W. Elverum & Sun, Ltd)

Understandably, amidst a productive couple years and within a career suffering from few downturns in output, it may be hard to see at first glance how perfectly diagrammed a summation of Phil Elverum’s stylistic history is in this year’s diptych of full-length recordings, Clear Moon and Ocean Roar. Together, the two are as demonstrative of Elverum’s Mount Eerie project as 2001’s career-defining synthesis The Glow, Pt. 2 was of all of his earlier sensibilities as the Microphones. The necessarily divided approach to Clear Moon and Ocean Roar as separate pieces hits all the bases that round out Elverum’s best works in both incarnations, but each takes its time thinking a little harder and more deeply about each song as a piece on Elverum’s chessboard. That freedom to wander in more big-picture terms has always been Mount Eerie’s relative strength, and the scholarly degree to which Elverum catalogs his own multifaceted topography makes for not one but two deserved victory laps this year.

The more restricted, intimate Clear Moon came suddenly in May like a fresh afternoon rain shower, and holds itself close enough to share an umbrella, and some strummed tunes, around a smoldering evening campfire. It’s as dark and cavernous as the wet forests that populate all of Mount Eerie’s work, but Phil’s warm whisper makes it clear that the storm is always just about to break. Think the somber hopefulness of Lost Wisdom’s (2008) evergreen gospels let loose to run free without anything but vistas of introspection to guide them. A perfect compliment, Ocean Roar picks up where Clear Moon’s afternoon shower leaves off, rising up into the atmosphere as the clouds gather steam and Elverum’s guitar becomes a lightning rod for the electricity of rock and roll cataclysm. Pushing the experimental metal aesthetic of Wind’s Poem (2009) to new heights while at once relating it more fully to his other stylistic leanings, Ocean Roar captures the culmination of Elverum’s attempts to transform the basic elements of pop music into true forces of nature. For safety’s sake, board the windows—besides, you can hear the songs better that way.

► “House Shape”

► “Ocean Roar”

P.M. Goerner

28 :: Laurel Halo

Quarantine

(Hyperdub)

Man vs. Machine: one of modern music’s most intriguing, ongoing struggles. Kraftwerk, White Noise, Brian Eno, Laurie Anderson, Björk, any number of krautrock-leaning or progressive electronic acts over the years have, in their own very unique ways, done much to expand and refine theories regarding our place within our continued, likely futile, push toward technological harmony. And so 2012 has been marked by another coincidental yet collective attempt at reconciliation with the analog age. Andy Stott, Julia Holter, Holly Herndon, Burial, even Chromatics all seem preternaturally concerned with bridging the gap between our imperfect vessels and the superficial, yet dangerous, machines currently at our disposal, but the shape-shifting Laurel Halo arguably pulled off the most impressive feat of all with Quarantine. She’s imbued a cold mainframe of hand-fashioned circuitry with a personality and liquid warmth uncommon not just for Halo—who’s prior work either subsumed such spirit or, in the case of her King Felix alter ego, disregarded it altogether—but for many of her contemporaries, who often lean on two-dimensional contrasts and atmospheric detritus to gird process-based experiments.

Quarantine’s rainbow-splashed manga artwork suggests something far bolder and more wide-reaching than any genre tags can contain. Indeed, it’s a kaleidoscopic trip from Halo’s heart through to her cerebellum, rippling currents of vocal and instrumental manipulation doing less to obfuscate her performance than heighten the white-hot interplay between her best talents. Occasionally she isolates—“Years,” in particular, is a bracing showcase for Halo’s voice, never before left so naked or vulnerable on record—but more often than not she casually braids her transmissions through the bottomless expanse of her compositions, floating ominously in utero (“Joy”) before crawling out, confident and clear, amidst vocal lines cascading one atop another (“MK Ultra”) into terrain as ghostly as it is radiant (“Carcass”). Halo maintains an impressive momentum throughout, an intuitive pace, blurring the line between interludes and standalones (I’d venture to say that it’s not coincidental, for instance, that “Holoday” elicits the same pangs of skewed comfort and shrill disorientation as “Morcom,” pieces that pit Oneohtrix-style samples against Halo’s suffocating pleas) until things fail to ebb and flow so much as react instinctively to their surroundings.

And yet the sheer aural experience of listening to Quarantine belies what may in fact be the album’s most fascinating revelation, that being the fully formed arrival of Laurel Halo the woman, the individual, the essence. Electronics have long been used to frame discourses on alienation and psychological discomfort, but even in this context Quarantine feels like an uncommonly sad and lonely record. The way she pitch-shifts her vocals on “Carcass,” the way she filters her declaration that “Nothing grows in my heart, there is no one here” on “Tumor,” or the way she seems to be kicking and screaming beneath the cauldron of the aforementioned “Joy” and “Holoday”—all these small instances help to intensify an ambiguous but tangible portrait of an artist coming into her own as not only a producer but as a songwriter. “One foot in front of the other / Forward motion’s the only answer,” Halo encourages on “Thaw.” And while the sentiment seems obvious, it can just as easily be read as creative wisdom, perhaps even for her contemporaries. One thing’s for sure, with Quarantine, Laurel Halo is now way out in front.

Jordan Cronk

27 :: Cloud Nothings

Attack on Memory

(Carpark)

Dylan Baldi places his biggest gestures at the front of Attack on Memory. “No Future/No Past” churns its way over three chords, twelve words, and five minutes. It’s a counterintuitive opener for such on an album so visceral, a seeming statement of apathy that becomes slowly unhinged in Baldi’s adenoids and in the hands of his tom-tom beating, guitar shuddering band. When it explodes in the final section, the listener understands—is made to understand—the band’s modus operandi: the past has disappointed you, the future can only do the same. There can only be now, and it can only be made manifest by a sheer teenage anger and the power of our music.

It sounds like a ludicrous claim, but he’s proven right by the time “Wasted Days” wrings out its ragged final chord almost nine minutes later. Many have pointed to the obvious precedent of the Wipers’ totemic “Youth of America,” in a similar tempo, possessing an equally “un-punk” runtime, and with an identical monochordal vamping scheme. To these ears, Baldi stake out enough new ground to make a credible gold claim on this idea (for one thing, drummer Jayson Gericz, as recorded by Steve Albini, makes mince-meat out of Greg Sage’s production). It is one of the most thrilling sounds of the year, capped off by the nineteen year old singer raging “I thought / I would / Be more / Than this”—less a betrayal of his callowness and more a statement of faith, more than earned by his sheer talent.

Cloud Nothings haven’t abandoned pop hooks: “Fall In” and “Stay Useless” are two iron-wrought pop songs as ever written, furious blasts of inchoate rage at the writers’ expanding horizons, and realizing that they’re narrowing as he sings, or screams. They’re songs Jawbreaker, who weren’t hurting for such material, would’ve killed to have written, just like finale “Cut You” and even the combustive instrumental “Separation.” Truth be known, the two poles of Baldi’s songwriting don’t quite attract on one album as short as Attack on Memory. His backing band’s ferocious playing, however, ties them together, and delivers sure-fire single “Stay Useless” with as much violence as the Drive Like Jehu sounding “No Sentiment.” They are now, by default, Cloud Nothings, and as such obliterate Baldi’s previous solipsistic turn with the moniker. As much as it is his, it’s their attack on an old memory.

► “No Sentiment”

► “Stay Useless”

Christopher Alexander

26 :: Liars

WIXIW

(Mute)

Liars are inconsistent in the best possible way. Never afraid to pursue an idea to its illogical conclusion, they’ve created hymns of great beauty (“The Other Side of Mt. Heart Attack,” still) and unlistenable shitfests like They Were Wrong, So We Drowned (2004). But even at their worst, the band has a way of wringing creative mana from the most banal and casual of musical elements. So when they turn their attention to vast, sometimes much gentler electronic vistas on WIXIW, the results are predictably fascinating. “Octagon” sounds like Autechre scoring a conspiracy theorist’s nightmare, while “Brats” and “His And Mine Sensations” explore a skewed digital reinterpretation of the sort of lanky post-punk they explored in their early years. On the other hand, fans of the band’s more ethereal sides can find solace in opener “The Exact Color of Doubt,” wherein frontman Angus Andrew spreads his breathy melodies against a skittering drum machine and colorful ambient soundscape.

Although most of the album is quite good, “Flood To Flood” stands out as the single most forceful and memorable composition the band’s concocted since Drum’s Not Dead (2006). Over a cyclical, collapsing arpeggio and vertigo-inducing guitars, Andrew implores another with stark, unalloyed directness: “Teach me how to be a person / Bring me breakfast after dinner.” The song captures everything the band does best: simple but affecting melodies, instruments put to uncommon but ingenious use, and a powerful sense of momentum. If dude keeps writing songs like this, I’ll be the first to make him some pancakes.

► “No. 1 Against the Rush”

► “Brats”

Brent Ables

25 :: Frank Ocean

Channel Orange

(Def Jam)

Frank Ocean’s mercurial, deeply personal, achingly sad debut seems relevant in a bigger way than a R&B record belies. Channel Orange signifies from behind the sheen of formulas, complexly rippling with double-meanings, irony, anger, revelation, confession, and the sinking suspicion that the whole thing is an intellectual exercise from an extremely intelligent songwriter. It’s not duplicitous; it captures the equivocating, confused state of the album-as-statement in 2012. It reads like a diary in random intervals.

And of course, though I feel conflicted saying this, any review of the significance of Channel Orange is tied inexorably to Frank Ocean’s decision to come out of the closet on the internet. I can’t think of many gestures more public, or contemporary in feeling, than that—that exposed nerve of a world simultaneously interconnected and weighed down by complexes and old prejudices. Our communication with one another has become a mirror. Our consumption of albums like Channel Orange has become a mirror. How did Ocean’s deeply personal letter make you feel? Was it his letter that made you check out his record and take a greater interest in his lyrics, maybe even identify with him? That’s certainly the case for me—and what does that say? What does that say about 2012? Frank Ocean isn’t messy the way, say, Girl Talk is messy. It’s messy the way it’s messy to be a human in an imperfect world.

It helps that the album is the fucking jam, and Frank Ocean can sing like a motherfucker. As Brent said in the opening line of his review of the album: “People want to talk about Frank Ocean, but I just want to listen to ‘Pyramids.‘” And maybe that’s what makes Channel Orange so complexly satisfying. Sure, it’s a heartbreaking snapshot of aggregator angst. But it’s also a prodigious talent navigating these troubled waters more naturally than most are able to. Channel Orange feels like the beginning of what might be a long relationship.

Conrad Amenta

24 :: Spiritualized

Sweet Heart Sweet Light

(Fat Possum)

The last several years have been nothing if not encouraging for nostalgia acts. More than ever before, promoters seem to want nothing more than for old bands to reunite and for musicians that have for whatever reason survived beyond a ten-year run to play songs, if not albums, released decades ago in their entirety for crowds frustrated by the very notion that the musicians they love might have moved past the songs they want to hear over and over again into infinity. Simon Reynolds and others have leveled criticism at this trend, and with good reason: it doesn’t naturally lead to forward motion, or to any motion at all.

Enter Spiritualized’s Jason Pierce, who, when not surviving near-death experiences with debilitating diseases, spent the bulk of 2010 performing his uncontested life’s masterwork, 1997’s Ladies And Gentlemen We Are Floating In Space, in its entirety, and as a consequence found himself inspired to step up his game for the first time in years. Unlike 2008’s fine, but unmemorable Songs in A&E, Sweet Heart Sweet Light sees Pierce meditating on his three inescapable subjects—God, love, and drugs—to striking results for the first time in years. He embraces sprawl, yet keeps tight pop songs like “Little Girl” within the relatively brief confines of four minutes, and keeps his excesses and pretenses in check. He even reunites with New Orleans mainstay Dr. John for a song that sounds nothing like the cacophony of their previous collaboration, Ladies and Gentlemen finale “Cop Shoot Cop.”

But most of all, where Pierce once sounded heartbroken—and in likely drug-addled orbit because of it—on Sweet Heart Sweet Light he sounds utterly in the now, as if he knows his time is limited and he has to make the most of it. For evidence of this, look to closer “So Long You Pretty Thing,” one of the year’s most arresting songs and a potential farewell, if it is one, that could very well be unrivaled. It begins as a duet with his eleven-year-old daughter, Poppy, before blooming into what sounds like a gorgeous goodbye to his dreams of success as a musician, to his sanity, and to everything else one could possibly lose in seven-and-a-half minutes, rendered supermassive by a gigantic orchestral arrangement and accompanying choir. For a record born out of survival—and a sudden need to one-up oneself—it’s a grim, yet deeply moving, vision indeed. And, if nothing else, it certainly sees no salvation in empty revivalism, no matter how strong a case it presents for revisiting the past as a bridge to the future.

Andrew Hall

23 :: Deerhoof

Breakup Song

(Polyvinyl)

I’m very sad Deerhoof has broken up with me, but also happy because Deerhoof broke up with me with a bunch of songs that sound like candy apples taste, like Play-Doh feels, and like the texture of cotton candy. But also like midnight and exhaust pipes, and Eddie Gale’s Ghetto Music and The Jersey Shore, and pineapple and wet naps, and BBQ ribs and calamari, and chocolate cake and Synergy, and rubber ducks and real ducks and wooden ducks and drawings of ducks, and spraypaint and fumbling, and Sarah Jessica Parker and Jesus, and the letters “L” and “U,” and the Doppler Effect but also being right in your grill, and Aroldis Chapman and financial decline, and Amanda Bynes and the sticky bark of a tree, and old cardboard and young plastic, and Svetlana Zakharova and chicken dumpling Bachman Turner Overdrive, and wave-particle duality and the Přídolí Epoch, and Michael Kors and Michael Jackson, and urban gentrification and felafels, and paint drying and airplanes rocketing over head.

But also Deerhoof, because at this point Deerhoof is Deerhoof, and let’s ask ourselves: is it possible for Deerhoof to make a bad album? I dunno, but the tracks of my tears are dancing, which makes my face feel funny, which makes me smile. Breakup Song maybe isn’t Deerhoof vs. Evil, but Breakup Song is Deerhoof breaking up things and pairing them back together like they were the same thing anyways, dummy.

► “The Trouble With Candyhands”

► “Fête d’Adieu”

Mark Abraham

22 :: Jessie Ware

Devotion

(Universal Island)

The dominant narrative surrounding Devotion is one of unlikely pop stardom, of a former backup singer who almost quit the whole gig suddenly launching her way to a solo deal on the back up of a few notable guest spots on tracks by established producers in the UK bass scene. Without ever acknowledging it, critics simultaneously use the commercial pop landscape as both an object of derision and laudation, and their dream is someone who can both maintain some historical ties to underground music trends while also effectively abandoning them, rising above it for something more ambitious.

On the one hand I get it: sometimes an album just sounds like it belongs in the stratosphere, and the person at the centre of it all seems to have written her own fame into the music itself. On the other hand, Ware and her voice—admittedly as commanding and magnetic as everyone says—is only half the story. The other is the production, or perhaps more accurately Ware’s ability to curate a team (led by Dave Okumu of the Invisible) with the uncanny realization that not every track is going to lift the torch. They save what, from a purely pop point of view, might be a sagging middle of the album: thus the elastic percussion becomes the best part about “Still Love Me,” that woozy, tremoloed Stevie Wonder keys the highlight of “Sweet Talk.” “Something Inside” was already a great song, but without her voice it could’ve still been a warm, bubbly highlight from early 2000’s bedroom electronica.

The ability to share space in the interest of crafting a great track rather than just seeking out a platform for a set of vocals that could easily hold their own is, ironically, what makes Ware such a refreshing and iconic pop star. With realistic ambitions and a great deal of humility (“I feel like I got away with it!” was her reaction to her own growing fame), her lyrics feel like the latent widescreen romance in everyday relationships. When was the last time you heard an ode to the ambivalent and contradictory forces at work in keeping a couple together like “Wildest Moments”? Even the moments where Ware’s voice isn’t doing very much the production makes her sound huge, giving the song the conviction the words can’t muster.

Ultimately Devotion charts the mutual sacrifice of love that goes beyond rational explanation. It all comes to a head on the stunning “Taking On Water” whose narrator lets herself drown in order to hold onto someone who she lacks the strength to pull up. A great voice, after all, still has to realize that sometimes words can fail you.

► “Wildest Moments”

► “Running”

Joel Elliott

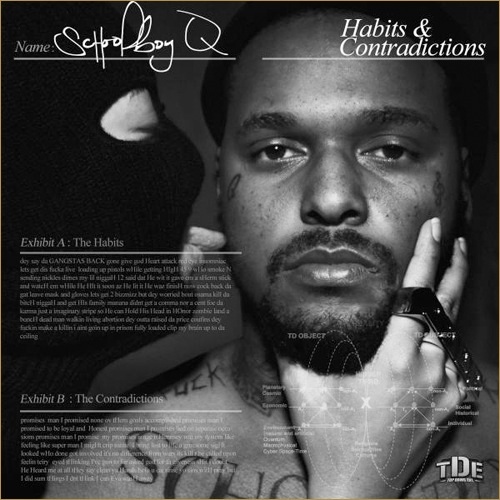

21 :: ScHoolboy Q

Habits & Contradictions

(Top Dawg Entertainment/Interscope)

Ab-Soul recently boasted on Twitter that his Black Hippy collective “made it cool to be smart again” in rap. Habits & Contradictions, the second album from Hippy’s German-born ScHoolboy Q, is my rebuttal. That’s not a criticism: this album’s glorious simple-mindedness is not born of stupidity, but from a certain benign wisdom. The wisdom of: pills, weed, 40s, other human animals, saying the word “fuck,” and setting out with absolutely nothing to prove. Nothing rare in rap, then, except that last bit. ScHoolboy Q just sounds so damn comfortable on this record. It’s a different kind of hard work. And it’s infectious: if you don’t just sort of collapse onto your soul’s sofa every time Q hands off “My Hatin’ Joint” to those flutes, then you work entirely too hard. Kendrick Lamar may have been Black Hippy’s genuine breakout success in 2012, but listening to this record, you get the sense that conquering the world was never really on ScHoolboy Q’s agenda anyway.

► “Hands on the Wheel”

► “Blessed”