Features | Top 30 Albums 2013

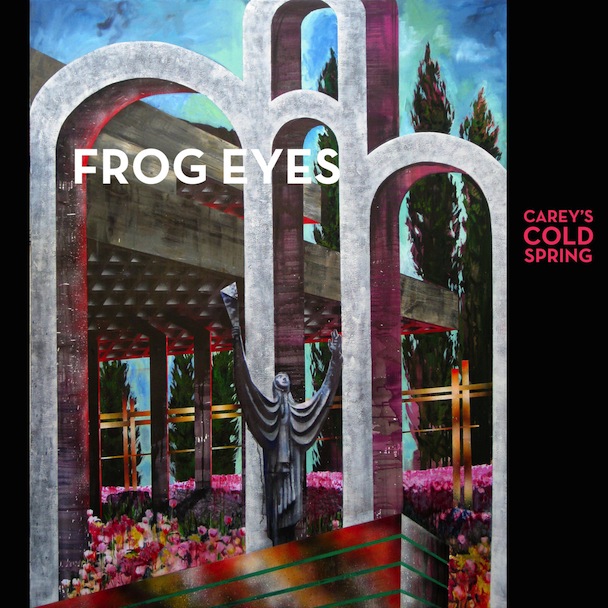

1 :: Frog Eyes

By Brent Ables | 19 December 2013

Carey’s Cold Spring is a record of life. It is a document and a teaching: it wants you to be okay. It says, the world is sick; the world is sad; but what’re you gonna do but try and make it glad? It says, don’t give up your dreams. It says: reform. And what it says sounds strange to us in 2013 because we aren’t used to speaking to each other this way, with a quivering voice and a true heart. This is not a record that has much use for the smirking luxury of irony. It quietly refuses to be part of a culture complicit in its own exhaustion. Perhaps this is because it was created out of the knowledge that real exhaustion, if you follow it through long enough, leaves you with a desire for life whose phantom stimulation can only simulate. The knowledge that suffering doesn’t have to be for nothing, even if all you will ever know is suffering. Carey’s Cold Spring won’t heal anyone, and it won’t tell you how to raise yourself from the dust. But you will find it easier, after listening, to do those things on your own if you need to. This is only a record. But this record is a blessing.

*****

“Reform for the light.” Actually, it’s not a record. It’s a self-released digital download, and you can find it right here. And if you don’t need to reform? It doesn’t matter. This is an entry in the art of sound, and in its cumulative force, grace, and impact it is unrivaled by anything else released this year. These songs sound as though they were carved by wind out of the hills, taking shape as crests and valleys rather than verses and choruses. It’s not a map, it’s the territory; will, not idea. “An air worth recording.” I guess it’s a rock album but it doesn’t sound much like any other rock album I could name. Frog Eyes has always traded in a pre-modern romanticism of the macabre, but there’s something more elegant at work here. The chaotic bluster of the preceding records has been reigned in, the energy redirected into pure intensity and a resoluteness abstracted from all resolution. Carey Mercer used to play guitar like Jimi Hendrix, now he plays guitar like Rodin. If Paul’s Tomb (2010) had one fault, it was its failure to find a proper balance between Mercer’s frenzied narration and the punctuated bursts coming out of his dying amps. Here they complement each other like 3 AM and a glass of whiskey.

The 9 songs on Carey’s Cold Spring are stories, each fragmented and abstract but centered around imagery as memorable as an exorcism. “The Road is Long” belongs to Judith, a troubled woman we last encountered on Paul’s Tomb. Judith is besieged by angry harpies and a vengeful sea, but she can’t escape because the road is blocked by a messianic cop stealing holy clocks. “Don’t Give Up Your Dreams” is concerned with a nightmarish insurrection represented by Black Bloc Rita, who spouts inspirational maxims and beats up maids (in disguise) when she’s not trying to steal your car. Sometimes the subjects don’t even have names, like the doomed spirits of “Your Holiday Treat.” (“Born in a sack! / Born in a sign! / Born in a bottle at the bottom of the brine!” Mercer’s lyric sheets are replete with exclamation marks, his passion overflowing into his punctuation.) Scattered throughout these stanzas are the maxims that form the epiphanic core of the text, and that Mercer’s arrangements privilege above the narratives. If there is an interpretive question raised as to how the affirmations of the surface fit over the strange, unsettled depths of these broken souls, it properly belongs to the listener negotiating that conflict in her own.

Engaging Mercer’s lyrics for any time at all brings home just how rare this kind of literary richness is in contemporary music. Is it geography? In 2006, on the opening track of Destroyer’s Rubies, Mercer’s friend Dan Bejar memorably dissed the entire American underground on the basis that there’s “not a writer in the lot.” But he didn’t say anything about Canada. The same year also found Bejar and Mercer teaming up with fellow British Columbian Spencer Krug for the Swan Lake project. It sounded like a boar dying in a tar pit, but I challenge you to name a more formidable gathering of lyrical talent outside of hip-hop this century. Sure, Bejar has a maddening habit of resorting to freewheeling Dada collage in place of considered content, and Krug’s awkwardness sometimes skates by on barbarian charisma alone. But Mercer’s prose has remained sharp and expressive, his images harbor an elemental force, and his work is thematically concerned with only the deepest and highest of human experiences. If there are better writers in the American underground, I haven’t heard them.

*****

“Reform, before the thermostat cracks and gasps.” Spring in Canada can be quite cold. The last one froze me straight through. Thoughts that had once been light and mobile condensed into so many dull blocks of ice, their weight leaving me unable to lift my head from the pillow for days at a time. When nothing around you moves and time is the only form of change left, you discover you still have the power to curl it into refrains. To give shape to the void by harnessing becoming, the way Mercer does at the breathless apogee of “A Duration of Starts And Lines that Form Code.” 1, 2, 3, 4. 1, 2, 3, 4. 1, 2, 3, 4. “We must raid the dayside!” Guitars crashing like the tide. This is perhaps the most ecstatic, cathartic moment on the album and it doesn’t really mean anything. Mercer’s not a writer, he’s a songwriter. He insisted on this point in a recent interview, speaking of Bejar and, by extension, himself: “If he is a poet, he must write poetry….Take the music away, and you don’t have a poem! You just have a song without music, the saddest thing that I can think of.”

In this light, the song title takes on new meaning. “A Duration of Starts and Lines that Form Code” is, presumably, a description of a string of Morse code, where a sequence of meaningless elementary symbols combine to form meaning. On its own, an assemblage of symbols, events, and names is just “a song without music;” the synthesis that a master craftsman like Mercer gives them is something wholly intangible and irreducible to its parts. Something like what film critics call mise-en-scène, but more concentrated and intuitive. And it has the effect of lending the words a weight and an intensity that a poem could never convey. In the case of “Starts and Lines,” what Mercer wants to convey is unmistakable: “You should clean up your cuts / And it will fall away / Your shame shall fall away / Your shame shall fall away / And the bad little habit’s got to stop.” When you hear that last line, you know exactly what habit he means, not necessarily because you mean the same thing but because the song speaks for both of you.

Habit is a function of time, and in this sense you can choose either to let it repeat indefinitely (1, 2, 3, 4, “On and on, on and on, on and on”) or you can raid the dayside and move to higher ground. To shake off the patient, planless evils of habit—is this not the very meaning of reform? But you need something to put in its place, something to fill the time. “Is this love that you’re missing?” Then get off the internet. Or is it: “We want to be alone / We want a night so slow / We want to taste an air worth recording.” Should we “smash an apple on the face of the state?” If Carey’s Cold Spring has a final answer, maybe it’s the one from “Needle in the Sun:” “Forget the beauty of the rains / It is beauty that moves us along / Into the grass that strokes our graves / We shall be brave, we shall be gay / And stick a needle into the sun.” It’s an ambiguous message, praising beauty as what sustains us after telling us to let it go. Is it an acceptance of time, and where it leads us? Or a revolt? I think it’s both, or neither. And an admission that it doesn’t matter, because time will eventually claim you either way.

But you’re not there yet. Right now, you still have the elegiac beauty of Carey’s Cold Spring to move you along. All that I’ve said here, all I could say, merely hints at the power and depth of this record, and indeed of any Frog Eyes album. Maybe all that’s left to say then is just how immensely satisfying it is for me, for a lot of the staff, and likely for some of our longtime readers, to see this band finally take the top spot on a CMG year-end list. But forget about that. This isn’t a record, it’s a call to action. It says, focus on the fictions that move you and make them real. Don’t give up your dreams. I’ve heard talk in dreams about incredible songs where the body becomes a tonality of the earth. They sing of a place where the soul shall rise, like a burning shade of light. And nobody shall die.

► “The Country Child”

► “Needle in the Sun”

► “Claxxon’s Lament”