Features | Articles

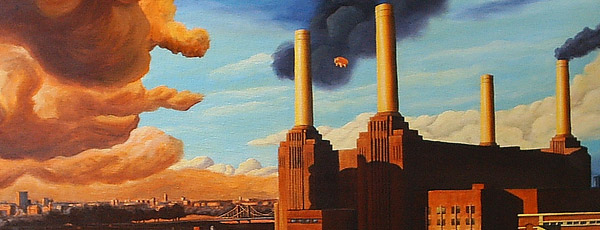

A House Full of Pain: How the Greatest Punk Album of the '70s Was Made by Pink Floyd

By Brent Ables | 6 August 2013

A conventional narrative of Pink Floyd might go something like this. In mid-1960s London, four working-class musicians with a proclivity for experimentation bolstered by the psychedelic zeitgeist of the time come together under the leadership of a brilliant songwriter named Syd Barrett. From the beginning, the Pink Floyd Sound (as they are called in the early days) make their name with a distinctive mix of tight, high-wire pop ditties like “See Emily Play” and drawn out, don’t-bother-listening-sober jams with cosmic names like “Interstellar Overdrive” and “Astronomy Domine.” The band finds quick success, thanks in large part to cutthroat management, and the pressures of fame along with his latent schizophrenia lead bandleader Barrett to a mental breakdown from which he would never recover. In his stead, Roger Waters and new guitarist David Gilmour take creative control, spending the late ’60s and early ’70s forging the band’s signature style. This aesthetic, which drifted indifferently somewhere between the warm enclosures of childhood and the dread emptiness of space, was captured in its purest—and arguably best—form on 1971’s sublime Meddle. But the Pink Floyd that people now know—the classic rock dinosaur anyone growing up within earshot of classic rock radio could be forgiven for wanting to forget entirely—had yet to show itself in these halcyon days.

With Dark Side of the Moon (1973), Pink Floyd created a behemoth that still holds the record for longest time spent on the Billboard charts (remember those?). Dark Side propelled the now-mature band to the kind of international fame that would ensure close critical and public scrutiny of the band’s every move from then until eternity. More importantly for the band’s future artistic direction, it made them a valuable commodity to anyone associated with the group—including, most notably, EMI Records.

The effects of this parasitism began to make themselves felt on Wish You Were Here (1975), a conceptually peculiar album splitting epic tributes to Barrett with sarcastic satires of the music industry like “Have a Cigar” and “Welcome to the Machine.” Next came Animals (1977), which found an increasingly bitter Roger Waters (who had gradually established himself as bandleader over the course of the ’70s) so determined to avoid a hit single that he constructed an album with three ten-plus minute epics bookended by a brief prologue and its refrain. Despite the lack of radio hits and persistent vitriol, the album did well. This pattern would essentially repeat itself with The Wall (1979), a truly fucking awful spectacle of rock egoism fellating itself to the tune of a never-ending palm-muted D-minor chord. One of the conceits of the record was that rock music fans are as mindless and stupid as fascists. It sold twenty million copies.

There’s more to the story, but it only gets worse from there. Also, punk happened. When the Sex Pistols came storming into the world and changed the face of guitar music forever, they did so in direct response to the excesses of bands like Floyd: Johnny Rotten was known to wear a Pink Floyd shirt with “I HATE” scribbled above the band’s name. It makes a certain amount of sense. As wearying as the radio dominance of “Money” and “Comfortably Numb” was for an American kid like me in the ’80s and ’90s, it could only have been worse in Britain during the band’s reign. Moreover, no one could have served as a better scapegoat for the anti-conceptual immediacy of the likes of Rotten: the concepts were always the least interesting parts of Pink Floyd’s music, but they are perhaps its most recognizable. So they became the enemy. Never mind that the Sex Pistols were also signed to EMI Records; never mind that Johnny Rotten is himself more of a concept than a musician. The Establishment needed a face to spit in. But the punks didn’t look deeply enough. If they had, they would have realized that for the space of an album, Pink Floyd had already done everything they wanted to do and had done it better. Animals was already the greatest punk rock album of the decade, and punk hadn’t even been christened yet.

“But wait,” you might say; “Animals is not punk rock.” Which leads to an important question: what do we want punk to be?

First charge: Animals can’t be punk because it indulges in seventeen minute epics rather than the three-chord blasts of the Ramones and Sex Pistols. Punk rock is simple and direct, “Sheep” is long and cryptic. But didn’t Television, whose Marquee Moon debuted in February 1977, a month after Animals, sufficiently refute this axiom? The title track has a guitar solo as long as any David Gilmour ever recorded, and nobody questions Marquee’s punk credentials. Suppose we disregard length; purists will argue that the central tracks on Animals are closer to prog than punk, but I see no reason an album can’t be both. Consider what happens if we define punk by some formal model or another: we will have to admit Green Day and Sum 41 into the lexicon along with the Clash and Minor Threat. The sad story of punk rock is the story of an explosion of rebellious fury that eventually became one of the tamest, least provocative, most commercial sounds in the history of popular music. If punk is a style, then punk is absolutely and irrevocably dead and buried. If, on the other hand, punk is an ethos, then our perception of this moment in history changes.

Animals is, by some distance, the most venomous, bleak, cutting, ruthless lyrical document released by a major rock band in the 1970s. Roger Waters’ attempt to ward off radio is only the beginning of it: over the album’s three core tracks, Waters unleashes a furious condemnation of you, your family, your boss, your lover, and the depths of your corrupted festering soul. No one is safe. If you’re a capitalist baron lording over your vassals, you are (naturally) a Pig. You radiate shafts of broken glass; you’re hot stuff with a hatpin and good fun with a hand gun. You are a charade. If you’re playing the game to rise to the top, you’re a snarling Dog, and Waters sentences you to die alone rotting of cancer. And if you’re a good-natured Sheep, harming no one and minding your own sheeply business, why then you’re the worst scum of all. You’re so bad, Waters had to rewrite the Lord’s Prayer just to articulate how you’re going to be cut up and hung on hooks. In the course of these condemnations Waters pens some of the most memorable lines of his career, but that’s beside the point, and the point is that you and everyone you know is totally fucked. What is this but the punk ethos in its purest form?

A great album is made great by its form, however, as well as its content. What is so endearing—and so very, very punk rock—about the way the band presents this material is how they side with neither Dogs, Pigs, or Sheep, but rather with dogs, pigs, and sheep. It’s as though Roger Waters feels compelled to defend the animal namesakes against the humans who sully their images. Witness how, at the five minute mark of “Dogs,” David Gilmour ends a lyrical guitar solo and hands the track over to a dog for a minute. It’s a dog solo: rather the same trick Pink Floyd pulled on Meddle’s “Seamus,” except now with purpose. The band will repeat the trick with pigs and sheep, even going so far as to coax porcine snorts out of Gilmour’s Stratocaster. And yes, these moments are nestled among four minute synth escapades and the best guitar work of David Gilmour’s career, but even the guitar solos sound vital and urgent, trying to make us feel the horrors Waters’ biting satire can only hint at. It’s a concept album, but the concept is so perfectly realized that there’s nothing indulgent about it—nothing besides the pigs.

So I ask again: what do we want punk to be? One answer is, nothing. It died a gruesome death; let it rest. Another is: I’m waiting for the Fugazi reunion too, pal. But in a time where the prospect of music having any kind of political effect is all but unthinkable, the other answer is that we should cherish those bands that, if only for a track or three, articulately used all the resources at their command to expose the cruel lie at the heart of the capitalist machine in which we’re all caught. For the space of an album, before they disappeared up their own ass, Pink Floyd was that band. Question their punk cred if you want; all I know is that now, thirty-five years later, while Roger Waters goes before the United Nations in defense of Palestinian rights, Johnny Rotten is growing fat from VH1 reality shows and butter commercials. And as I think we can all agree, there’s nothing less punk than a fucking butter commercial.