Features | Awards

The Rammstein Award for Having Obscure Space Debris Commemorate One's Art

By Matt Main | 15 December 2011

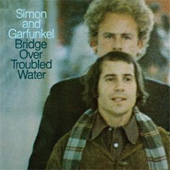

Simon & Garfunkel

Simon & Garfunkel

Bridge Over Troubled Water (40th Anniversary Edition)

(Columbia; 1970/re: 2011)

Bridge Over Troubled Water has probably been my favourite album of 2011, arising first from a simple appreciation of its opening track before unlocking the hidden treasures that litter this record as it progresses. To rank the songs according to any particular scalar would in a sense be redundant, so distinct and stylistically diverse that the flows between a large amount of the tracks are often dichotomous in themselves: “El Condor Pasa (If I Could)” to “Cecilia,” for example, or “Baby Driver” into “The Only Living Boy in New York.” Each song is very definitely a product of its creator and time in creation, simultaneously Paul Simon’s anguished inner monologue pertaining to his slow-burning inspiration and the now-infamous recording process, and also an artifact, a viewpoint or watchtower over the age it was born out of. The fact that there is still a market for this album to be reissued once more on its 40th anniversary in 2011 speaks volumes—beyond cynical asides about financial predicaments—in relation to how it still self-sufficiently resists antiquation.

Today, of course, Glee cover this stuff; somewhere out in space, asteroid “91287 Simon-Garfunkel” floats harmlessly onwards. Rather than bearing cultural significance in sentimental trivialisation, however, the impact of these songs lie often enough in their emotional weight. Here, on its anniversary outing, the album is augmented by a second disc of live recordings from a six-show tour embarked upon in November 1969. It is disorientating to hear songs like “Song for the Asking” and “Bridge Over Troubled Water” announced as “new” to little or no reaction from the devoted audience, the album still two months short of release. The latter is juxtaposed with “The Sound of Silence” (1965), the contrast in initial reception deliberately emphasised: the first guitar notes of “The Sound of Silence” are met with rapturous anticipatory applause, while “Bridge Over Troubled Water” receives no apparent recognition following Art Garfunkel’s brief introduction. Yet by the end of each, the audience offers a standing ovation, earned largely by the unrestrained emotion present in both recordings. Garfunkel’s delivery in “Bridge” is flawless, each note matched precisely to its recorded counterpart, every delicacy drawn out and fulfilled. It is no coincidence that this song was one of the few Elvis could never better when added to his performing repertoire, unable to fully marry his aesthetic to the uncertainty of the creative process—both believed the other should record the vocal part—underneath the reassuring offer of comfort the song sought to convey.

This uncertainty spills over into the most poignant and heartfelt cuts from the album on more than one occasion. The live version of “So Long, Frank Lloyd Wright” has Garfunkel explain it as a song simply dedicated to the remembrance of architect Lloyd Wright, but this is merely ostensibly so; the song’s farewell nature is as much Simon’s ode to Garfunkel’s increasing absence from the creative process as it is a tribute. Famously, producer Roy Hallee even cries “so long, Artie!” on the recorded version as the final vocal line fades out. It is curious that such a relationship of tension proved so ultimately fruitful—Simon barely even attempts to disguise his addressing Garfunkel in “The Only Living Boy in New York.” He encourages the recipient to “fly on down to Mexico” (a reference to Garfunkel’s pursuit of his acting career), leaving him to write alone. The simplicity of the loneliness bears an endearing innocence, absent of any real malice despite its melancholy. He shifts a lyric away from unbearable desolation with merely two words, “I’ve got nothing to do today but smile,” refusing to allow his alienation to overcome. “The Only Living Boy in New York” is the sound of weight lifting from one’s shoulders, the strums heavy and cathartic, relief sweeping through in the form of the swirling, multi-tracked voices.

Never do the duo ever feel the need to turn theirs gifts to acrimony. A fan interrupts during Garfunkel introducing the musicians on the live recording of “Mrs. Robinson,” which he considers briefly before jokingly responding, “the keyboard should be louder, huh? Which label do you produce for?” The response is friendly rather than bitter, and throughout the twosome pay due respect to their fans. Even when fans laugh during a slip-up in “Bye Bye Love” the two continue to play on with aplomb, innocently knowing nothing of the kind of public dispute so readily associated with the celebrity of today. Simon & Garfunkel never alter their craft in order to increase accessibility because their music is so all-encompassing: the claims of “Keep the Customer Satisfied” are filled with irony, as Simon never succumbs to the type of songwriting designed to placate critics or fans.

Instead, he sculpts out pop masterpieces, assembling influence from afar (“El Condor Pasa” originates from a Peruvian folk song) as he would do later in his solo work, particularly on Graceland (1986). “Cecilia” is built upon strokes of percussive genius and flighty woodwind, destined for much greater things than the desecration it received at the hands of Girl Talk last year. Bridge Over Troubled Water overflows with this type of excitement in places, yet changes mood at the drop of the coin. It’s almost sonnet-like in its abrupt disparity—how it runs with free-flowing energy (see: the horns in “Keep the Customer Satisfied” and “Why Don’t You Write Me,” “Cecilia”‘s introduction, the whole of “Baby Driver”) yet pauses as if it has arrived at an eighth-line moment of realization, and stops to reflect.

2011 also marked the year when the Beach Boys released The SMiLE Sessions in all their long-deserved glory, and basic parallels are obvious: both Simon & Garfunkel and the Beach Boys reside in a small, holy place where gifted songwriters make music that can abound with personality and insight and still not feel uncomfortable topping the charts. Like with SMiLE, there is merit in celebrating a landmark such as Bridge Over Troubled Water, a towering creation rising above and beyond the struggles that both marred, and perfected, its creation.