David Bowie

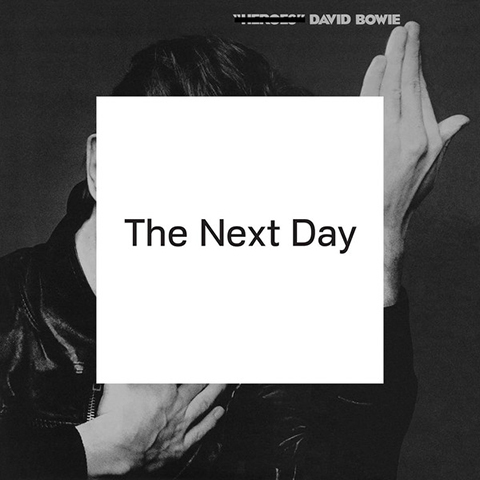

The Next Day

(ISO Records; 2013)

By Jonathan Wroble | 1 April 2013

Call it knowingly coy, but there was something majestic about David Bowie answering the question that so many have asked of him for years—where did he go—with a ballad called “Where Are We Now?”, the first single from his first record in a decade. The song, a curious choice to lead an altogether uptempo album, was perhaps picked for how it showcases Bowie’s trademark amorphousness, the way it starts with timeless cocktail chords and surges into a finale urgent and nostalgic at once, and its release was thus a multi-tiered Event: a celebration that Bowie hasn’t yet been reduced to shilling tunes in Starbucks, an invite to contextualize this new work by revisiting his ripened canon, and a reminder that while possibly alien the man is hardly immortal, that he still bends to the same snags of aging as us all. It’s a strange thing to reconcile, the wry and measured Bowie of today with the prolific and psychotic Bowie of the ’70s—all five or six of them—who sang of Orwellian doom and the bleakness of life ahead. Certainly The Next Day is at least in part an exacting and worthy challenge to the skeptic chameleon who observed in 1975 that “We live for just these twenty years / Do we have to die for the fifty more?”

Beyond that, this record also reenters Bowie into the arbitration of his own legacy, sort of like a sly old codger interjecting from the shadows as the world negotiates his will. The plain truth is that his influence has been cheapened, or at least unfairly simplified, by time; while bands like Radiohead shrewdly referenced his sound and artists like Trent Reznor his savvy in the ‘90s, the new millennium has spawned a legion of imitators generally too young to know Bowie but by his surface details, the androgyny and angular fashions and mutability, so their homage is more caricature than intelligent extension. If the genius of Bowie’s shapeshifting in his prime was that he belonged to no single genre or movement and could thus be adopted by anyone—name another musician who’s been appropriated by the BBC for its moon landing coverage, by the first wave of LGBT pride, and by Vanilla Ice—its outgrowth is a bastardization of his true brilliance: the songs. The Next Day has fourteen more, many good and some great, but more importantly it displaces for the moment even the best efforts of his followers for the sake of his fans.

The most satisfying stuff here is what sounds unfamiliar, much more than the tracks that send critics scrambling to find a sister song in Bowie’s catalog. Take “The Stars (Are Out Tonight),” which mixes together some trademark Bowie tricks—bellowing and intimidating horns, slithery backing vocals, guitar interludes that Robert Fripp could sue for—but renders them anew amidst offhand lyrics about Kate and Brad, seeming to prove that Bowie hasn’t spent the past ten years in cryogenic stasis. The chorus, longing and celestial, can best be described as virtuously alive. Similarly, “If You Can See Me” is a skittering gem, a meld of world music and acidic new wave that makes consummate fear sound triumphant. The title track is a nice bit of junk rock, Bowie declaring that he’s “not quite dying” like it’s a war cry, and on “How Does the Grass Grow?” he builds a demented and carnivalesque soundscape into one of the album’s catchiest moments and most pointed social critiques. On an album that often juxtaposes images of youth and dread—Bowie mostly plays an ominous, omniscient narrator on The Next Day, a comfort setting that affords him aloofness—there’s none more powerful than that of children lying in mud, grass sprouting from their blood.

Elsewhere things get sometimes weird, but never clunky. It’s bizarre that the most romantic and personal song, presumably about Bowie’s relationship with Iman, is called “Boss of Me,” stranger still that it hinges on a mammoth groove. Meanwhile, a country-inflected ditty about a school shooting called “Valentine’s Day” exemplifies a recurring complaint about The Next Day, that its arrangements are too slick and controlled. The track revolves on at least a half dozen riffs but dispenses them so cleanly that none ever surge to the forefront of the mix, the result an unbroken mass of sound that you have to practically dissect to truly enjoy—and even then the pieces sound like Mick Ronson caged and tamed. The same thing handicaps “I’d Rather Be High,” a Britpop throwback that contents itself being groovy, where a looser reading would make it funky. You can’t really blame Bowie for conforming to 21st-century quality control when it comes to the sound and scope of this record, but it’s not exactly something to be celebrated either.

What deserves celebration, or at least indulgence, are the glimpses of sublime execution on The Next Day, as well as Bowie’s skill in maintaining his mystique after all this time. He only outright flounders once, on “You Feel So Lonely You Could Die,” which forces so many inward references—the backing vocals from “The Bewlay Brothers,” chord progressions from “Rock ‘N’ Roll Suicide,” drums from “Five Years”—that it ends up tiring and frustrating. It’s like he’s trying too hard to belong to bygone days, while the rest of this album, often wondrously so, disregards the past and forwards the conversation to now. It’s fitting, given how Bowie’s golden period involved a string of characters built on schizophrenia, egomania, paranoia, and insomnia, that his secret weapon and strategy on The Next Day is a healthy dose of amnesia.