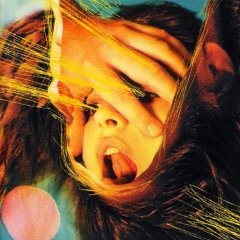

The Flaming Lips

Embryonic

(Warner Bros.; 2009)

By Joel Elliott | 23 October 2009

Regardless of what Wayne Coyne (and every other reviewer) says about Embryonic, it is not a series of “free form jams.” If it is, with the longest song (“Powerless”) at under seven minutes, then it fails pitifully, which might be appropriate, since Coyne has been rather open about his willingness to fail here. Coming off less like a Billy Corgan-style “fuck you” than a remarkably honest assessment of the band’s newfound sense of guidance (or lackthereof), this attitude is exactly why Embryonic—against all odds after the throwaway of At War with the Mystics (2006) and the intermittently fun but overly saccharine Yoshimi Battles the Pink Robots (2002)—sounds so incredible.

If Embryonic is free form, it’s more in effect than design: each track seems to start at the point of exhaustion, as if the freak-out happened before the tape started rolling, so a four minute track seems to be crushed under its own weight by the end. (And if this phenomenon, repeated eighteen times over 70 minutes, sounds tedious to you, this may not be your Lips album of choice.) Like all double albums before it—Blonde on Blonde (1966), Exile on Main St. (1971), Physical Graffiti (1975)—it is profoundly socially irresponsible, a panegyric to blowing your whole afternoon on the verge of getting up and doing something productive.

And yes, all these touchstones seem relevant, if only because Embryonic is a challenging major-label release, which should be a pointless distinction until you consider how rare that actually is. Consider, as well, the degree to which success at both the independent and mainstream level ebbs and flows at a monthly rate, and the rarity of bands with the mainstream clout and the well-established fan-base to do exactly what they want without fear of damage to their reputation and financial success. Now that you’re left with only a handful of artists, consider how many of those—like Dylan in the mid-‘60s and the Stones in the early ’70s—approach an album with very little to prove, interested more in deconstructing their past and letting ideas sprawl. If, like me, you’re left nearly empty, then you may have some appreciation for how exciting this record is.

Less cathartic than it is narcotic, a lot of criticism has already been leveled at the album for making the actual songs subservient to studio tricks, to which I can only respond that it’s about friggin’ time the band started playing to their strengths. Of course that might depend on whether you think “Wish You Were Here” is better than “Welcome to the Machine”; the latter of which haunts more than just “The Sparrow Looks Up at the Machine.” Now might be as good a time as any to deal with the unfortunate fact that the Lips have opted to cover Dark Side of the Moon (1973) in its entirety, a move so self-indicting it’s barely worth comment, except to note that Embryonic doesn’t sound that much like Pink Floyd and certainly not that stoner-naïve.

There may even be clues here as to what went wrong for the band over the last decade. Even before Coyne reduced himself to cheap political sentiment (“Free Radicals”), it seemed like the awe and marvel of Soft Bulletin (1999) had been erased even if the science-fiction elements remained. His songs of robots and magicians may have been fantastical and tongue-in-cheek but he sang them in earnest, an idea that Robert Pollard had successfully implemented except with the complete opposite production strategy. The fact that, as I think others at CMG have pointed out before, Yoshimi Battles the Pink Robots is one of a handful of records of the decade owned by a large percentage of twenty-somethings as evidence of “eccentric” tastes and disdain for mainstream pop music (even good mainstream pop music), says a lot about how the Lips, as Mercury Rev would later do with The Secret Migration (2005), were unable to perceive the point where mysticism stopped being subversive (not to mention good pop).

But with Embryonic, Coyne doesn’t seem to care anymore. And, paradoxically, the album seems far more serious than ever. The same spacy obsessions are still here, presumably, if you care to dig through the layers of fuzz and reverb to find them (or just peep the ridiculous astrological titles), but rather than seem laboured over in a way which destroys their potency, they carry the illusion (constructed as it inevitably is) of being channeled directly without a filter. As a result, all the loneliness and isolation that was force-fed to the listener previously is unleashed as a mere by-product of a fractured, almost nihilistic vision. Like Circulatory System’s Signal Morning (my other favourite album of the year, which runs the risk of pigeon-holing my tastes forever, but oh well), Embryonic outlines the limits of escapism, even if it does so in a far more overtly dark way. While on some level, this is a continuation of the idealism of At War With the Mystics, it takes on a completely different context here: “See the Leaves,” an over-dramatic record of environmental disaster, only really works because Coyne sounds detached, watching the world burn from space.

When the band does allow room for the self-conscious cosmic ballads, they seem like pregnant moments of calm. After the heavy openers of “Convinced of the Hex” and “The Sparrow Looks Up at the Machine,” the bottom drops out for “Evil,” with its alone-in-the-vacuum-of-space synth—the kind of abrupt shift of perspective and tone that suggests there’s some kind of attempt at a narrative thread here. It doesn’t really matter because its context sandwiched in between two acid-rock flurries—as well as that menacing bass tone that creeps in towards the end—allows it a pathos that maudlin lines like “I wish I could go back in time” wouldn’t achieve elsewhere. Afterwards, that same dynamic shift plays out even more abruptly in just two minutes on “Aquarius Sabotage,” which is split evenly between crude feedback-squalled jam and sparse Bernard Hermmann soundtrack (complete with NASA samples), erratically combining the polar origins of psychedelic music.

Shockingly, for a 70-minute album, very little doesn’t work. If anything the grace notes, when they do appear, are a welcome respite from the intensity of the album’s high points: the death march of “Powerless,” which re-imagines the erratic muted guitar solo from “Run Run Run” over the chilled glaze of Kid A (2000); the wind-swept space that lingers in “The Ego’s Last Stand”; the disembodied voices and orchestral rush of “Silver Trembling Hands,” which on any other album would be placed in a more privileged place than Track 16. In between lies interludes like “Gemini Syringes,” which features mathematical theories by Thorsten Wörmann (and, ok, is pretty much a straight-up Floyd tribute), and the oddly heartbreaking tape collage of “Virgo Self-Esteem Broadcast” which in other hands would play out like a parody of “Revolution 9.”

The story goes that Coyne et al. gave Dave Fridmann some raw tapes of ideas they’d been working on, with the intention of re-recording them in the studio, but Fridmann—lately possessed by the need to leave his comfort zone—convinced them to build on the fragments themselves. The technique pays off incredibly: while most bands that reach the kind of pastoral polish that the Lips have achieved in the past rarely look back, Embryonic takes all those tricks and pushes them into a live context, making them finally sound like an actual band again. It’s a reminder that the reason Can were so awesome was not because they somehow found a place for electronics and musique concrète within rock music, but that they managed to convince rock that what it desperately needed was those elements to rescue its forward momentum from dinosaur bands.

Mostly, Embryonic works so staggeringly well because it’s so unafraid to place itself in the lineage of unapologetically over-the-top rock albums. Which is a strange way to classify an album whose own creators almost dismiss it as an experimental one-off, but the key word here would be “excess.” Excess can be a deal-breaker, but when it works you just know somehow that it’s right (though, considering a good deal of dismissive or half-hearted reviews already out there, it’s going to take some convincing): this isn’t excess as an affront to fans, but an affront to fate. A big swan dive into the muck of failure without a life-vest.