Max Richter

The Blue Notebooks

(Fat Cat; 2004)

By Evan Goldfried | 20 November 2007

A few summers ago, I drove along the fog covered

Acadian coast in a white rental car with my brother

and sister. We parked at a beach to stretch our legs

and took a walk on the sand still wet from the

previous night’s rain; occasionally, something would break

the silence, a tiny crab half-buried, the shriek of a

gull flying overhead, hungry for food that left with

the tide. The feeling of stepping across the ocean’s

emptied bottom was so unimaginably alien, that I felt

everything and nothing. I simply stood in the middle

of vastness, staring at its endless pattern.

In my mind, The Blue Notebooks has become the soundtrack to the infinite. This ambitious second album from Piano Circus co-founder Max Richter economically arranges the unknown into an attainable, unpretentious, and altogether inviting composition. Richter, a self-described “post-classicalist,” combines the ambient minimalism of Aphex Twin and Boards of Canada with the emotional modernism of Xenakis’ orchestral works. Each track utilizes the bare necessity of instruments, a sustained cello note, a piano refrain, a steady Realktor-made beat, a church organ, each producing layers of imposing sounds fading in and out of consciousness.

Interspersed throughout The Blue Notebooks is British actress Tilda Swinton’s (Adaptation, the alluring Valerie Thomas) recorded passages from Kafka’s “Blue Octavio Notebooks” and Polish-writer Czseslaw Milosz’s “Hymn of the Pearl” and “Unattainable Earth.” Before each excerpt, a typewriter begins to clatter, and Swinton begins to read. Though used sparingly (and therefore with greater impact), Swinton’s accent subtly belies a deeper melancholy, giving each word deeper meaning. In one of the more chilling tracks, a piano plays while an airplane passes overhead, muted and far in the background; “Februrary the tenth, Sunday,” recites Swinton, “Noise, peace.” Then nothing; the piano continues, the airplane moves onward, both sounds quietly dying away.

The selected texts focus on both an isolated awareness of one’s surroundings and the passing of time. Kafka’s journal observes a sidewalk, once swept and covered again with dried leaves, of noticing the faint rattle of a mirror during a night walk, of cities on distant planes erupting with the dawn. After receiving news that his childhood home was razed, the narrator of “The Trees” dreams of flying through its trees once more. These images put forth by the quotes meld seamlessly into the music creating a timeless antiquity to the album. One could imagine The Blue Notebooks as the score to time-elapsed photography, in which a flower blooms and dies or a house is built and steadily decays into ruin.

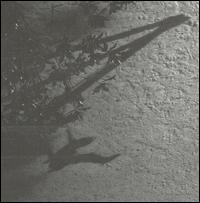

The Blue Notebooks’ cover art, a desolate landscape covered by the overhanging of trees and indiscriminant shadows, reflects the album’s dark yet hopeful ambivalence. Standing alongside the likes of Johann Johannssonn and William Basinski, The Blue Notebooks is repetitious like infinite space---changing with each listen while creating its own atmosphere. Listen to “Horizon Variations” and you’ll know there’s a reason why scientists spend their lifetimes trying to understand a black hole.

In my mind, The Blue Notebooks has become the soundtrack to the infinite. This ambitious second album from Piano Circus co-founder Max Richter economically arranges the unknown into an attainable, unpretentious, and altogether inviting composition. Richter, a self-described “post-classicalist,” combines the ambient minimalism of Aphex Twin and Boards of Canada with the emotional modernism of Xenakis’ orchestral works. Each track utilizes the bare necessity of instruments, a sustained cello note, a piano refrain, a steady Realktor-made beat, a church organ, each producing layers of imposing sounds fading in and out of consciousness.

Interspersed throughout The Blue Notebooks is British actress Tilda Swinton’s (Adaptation, the alluring Valerie Thomas) recorded passages from Kafka’s “Blue Octavio Notebooks” and Polish-writer Czseslaw Milosz’s “Hymn of the Pearl” and “Unattainable Earth.” Before each excerpt, a typewriter begins to clatter, and Swinton begins to read. Though used sparingly (and therefore with greater impact), Swinton’s accent subtly belies a deeper melancholy, giving each word deeper meaning. In one of the more chilling tracks, a piano plays while an airplane passes overhead, muted and far in the background; “Februrary the tenth, Sunday,” recites Swinton, “Noise, peace.” Then nothing; the piano continues, the airplane moves onward, both sounds quietly dying away.

The selected texts focus on both an isolated awareness of one’s surroundings and the passing of time. Kafka’s journal observes a sidewalk, once swept and covered again with dried leaves, of noticing the faint rattle of a mirror during a night walk, of cities on distant planes erupting with the dawn. After receiving news that his childhood home was razed, the narrator of “The Trees” dreams of flying through its trees once more. These images put forth by the quotes meld seamlessly into the music creating a timeless antiquity to the album. One could imagine The Blue Notebooks as the score to time-elapsed photography, in which a flower blooms and dies or a house is built and steadily decays into ruin.

The Blue Notebooks’ cover art, a desolate landscape covered by the overhanging of trees and indiscriminant shadows, reflects the album’s dark yet hopeful ambivalence. Standing alongside the likes of Johann Johannssonn and William Basinski, The Blue Notebooks is repetitious like infinite space---changing with each listen while creating its own atmosphere. Listen to “Horizon Variations” and you’ll know there’s a reason why scientists spend their lifetimes trying to understand a black hole.