Features | Lists

By The Staff

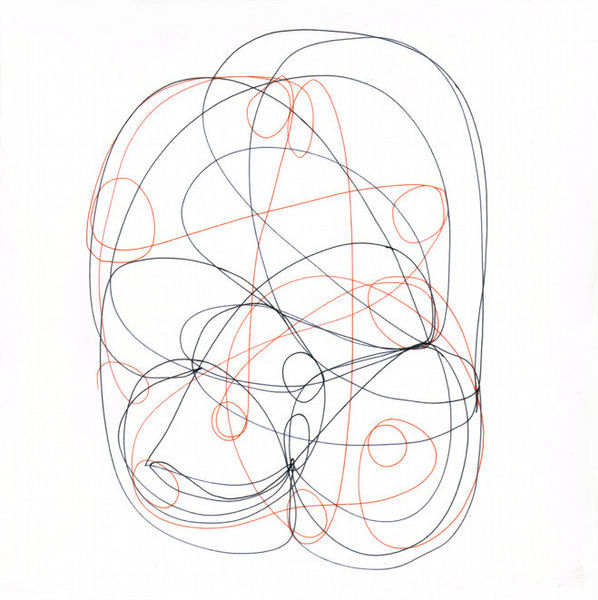

100 :: Jessica Rylan

Interior Designs

(Important Records; 2007)

The Glow loves balls. Not testicles, per se, but the sort of balls that Jessica Rylan has. Sterling, uncompromising artistic balls. Consider that her music is a bit like a glowing ball (singular), the kind that would bob above the words of a sing-along if only it still believed in things like words or singing or melody. Rylan channels an unbearable intensity into this tiny point of focus, solar flares concentrated into a laser point scrawl. Contrast level’s set at a billion to one; Interior Designs is a quiet album but loud, small and massive. “WTF,” you might say to me now, so here’s about as plain as I can put it: this is the sound of a sole oscillator fighting against its own linearity and eventually finding comfort in that it shares something essential with the timeless cycle of a roots progression. Of course, the clinical procedure of splaying music’s “interior designs” is actually an audacious and bloody operation sure to elicit numerous WTFs, even (or especially) amongst discerning listeners such as the Glow staff. But it’s a boon that the record just barely squeaked on to that staff’s Top 100 of the Decade list because it’s a telling hell of a way to kick this thing off. Here there be dragons.

Chet Betz

99 :: Ulrich Schnauss

A Strangely Isolated Place

(City Centre Offices/Domino; 2003)

If good records are meant to be enjoyed like cake then here’s the Vegan Chocolate Chunk, the one absolutely everyone can take a slice of. Ulrich Schnauss was a nineteen-year-old headbanger when he took his Ethereal 77 CD-Rs into Berlin, his fishing town origins long since behind him. A workshop/harassment campaign via post with the city’s hottest imprint, City Centre Offices, followed, and Schanuss tweaked his beats into a signature sound for Far Away Trains Passing By, his 2001 debut. One ripple of applause later, Schnauss went off and discovered swathes of light so ethereal even the angels had to squint, mulching them alongside his shoegaze fetish for this, his show-stoppingly transcendental sophomore record. Opening with a haze of runway static that builds into luminous trip-hop, A Strangely Isolated Place is 62 minutes of the most unpretentious, upbeat layering you can ever hope to hear (or what I like to refer to as So You Think You’re Ready To Start Tripping Balls: The Leaflet). I shit you not, I have witnessed this album convert everyone it touches—from wrist-slashing pizza waitresses to hardened council staff; from public school sociopaths to hangars full of grunts; from armed Yamaha riders to PhD students. Absolutely everyone can get something from this record, and all, somehow, without the notion of feeling slightly patronised. Be it via the funky train rhythms of “On My Own” or “Clear Day”‘s analogue breakbeats, Schnauss’ cooker of snowglobe tones sparks a noddable level of catharsis; his old website even used to get peppered with comments from nurses saying, “We use this shit for morphine!” Really.

What makes ASIP such a nurse-friendly entry is how Schnauss, being German, managed to balance his equalizer wizardry with some truly compassionate songwriting, each chord change revealing more every time you felt the need to spin it. And you will feel the need, believe me: even “Monday-Paracetamol,” the piss-call track, stuns with its space effects strata. Schnauss might have gone one layer too far on sequel Goodbye (2007) by attempting to sound like geology, but for a good few months back in 2003, Ulrich Schnauss was a gifted messenger, effortlessly transporting listeners home to a safe place they left twenty Christmases ago. And, trust me again, the only reason you could have anything to fear from that is if you’re nineteen years clear of Guantanamo.

George Bass

98 :: Charalambides

Joy Shapes

(Kranky; 2004)

In between mastering minimalist drone-guitar and shimmering post free/freak-folk, Charalambides took a short detour through the seventh layer of hell (which, as everyone knows, is only accessible via Texas) with Joy Shapes, an ode to everything uncanny and absolutely horrible and wrong. Taking inspiration from the notebooks of sixteen year old pill-poppers, Christina Carter found her voice and then lost it again: screaming “The rain shines / The sun falls” over and over again with increasing hysteria (but always, incredibly, maintaining some kind of pitch) until we finally get it that this thing should not be.

On paper it sounds like a disaster, especially since the band still pretty much rides one chord per track. What they do with that chord is another thing entirely: while on A Vintage Burden (2006) their multiple guitar tracks would drift out like ripples in a pond (and cheat a little by adding a second chord), here the tracks smear like a dark stain, equal parts Jean-Michel Basquiat and Francis Bacon. “Here Not Here” is the most distorted thing without a distortion pedal, lap steel guitars stretching and contorting the music miles beyond any kind of comfortable minimalism. This is an album of weird hauntings, even in its more inconspicuous moments. “Natural Night”‘s calm is so unbearable that Carter added lengthy stream-of-consciousness lyrics to the album art that, as far as I can tell, aren’t even in the song at all. The title track is the closest hint of the more peaceful waters to which they would later head, but that doesn’t make it much easier. An ode to utter misery (with another gem: “Oh my heart / You thought was a hotel”), it seems to document the moment of sorrow just before some kind of frightening resolve.

Joel Elliott

97 :: Boards of Canada

Geogaddi

(Warp/Music70; 2002)

See you, hopeless cynic, saying we only included this one because the lauded Music Has The Right To Children (1998) fell two years outside of our catchment. See you, who says this record is just The Animals Of Farthing Wood stabbed through with trip-hop beats. See you: you need to get your eyes tested. Eight years on from its so-so reception, the Boards’ Geogaddi has turned out to be one of the most covert growers of the decade, its overlapping secrets like speed-dating for conspiracy theorists. For starters, it has 23 tracks—already Jim Carrey shits himself. Granted, the addition of the silent “Magic Window,” a pause to raise the run time to 66:06 might seem an indulgence too far, but between the eerie network logotones and queasy beats the Boards are as gently captivating as ever, if not more so thanks to the wonky spread of genius throughout this album. “The past inside the present…” an answerphone drawls on “Music is Math,” a green flag for your descent into one fucked labyrinth of nostalgia. Blunt kaleidoscopes and Cold War psychedelia are the order of the day here, the brothers Sandison mining their collection of everything from Waco to Leslie Nielsen, from satanic citadels to 1969 in the sunshine. In fact, the Waco incident is like Geogaddi‘s recurring blackheads: tongue-in-cheek tributes to the tear-gassed Davidians crop up all over, most chillingly on “You Could Feel The Sky,” where flames crackle and women scream in the background. A deep voice whispers, “A god with horns.” An ominous bell tower tolls.

It’s not all codes and carnage, though, and alongside the insect gargling and devil chimes sidle some sweet and beguiling electronics. If you were lucky enough to grab the vinyl/digipack pressing way back when, with its hardback book cover and swirly Polaroids, you’ll know the Boards’ primary interest is reverie, and once they’ve gotten past the terror they’re able to crack out some brilliant treats. Dragonflies play trumpet on “The Smallest Weird Number,” while on heavier tracks such as “Alpha and Omega” and “Gyroscope,” whorling beats drown out banks of orgasmic statisticians. Geogaddi‘s continual blurring of what is/isn’t a song is what makes it so repeatedly arresting, and—regardless of your feelings on Soviet spy beacons or Lt. Frank Drebin teaching you how to film an anemone—you’ll surely melt at the gentle regret of “Over the Horizon Radar,” where decrepit technology takes one last breath before slipping from the wings of your memory. Now that, to me, is nostalgia—enough to make you mispronounce “geography.”

George Bass

96 :: Shugo Tokumaru

L.S.T.

(Compare Notes; 2005)

If we think of Boris as emissaries of Japanese culture adopting the scorched earth method used by Godzilla against the hapless citizens of Tokyo in the ’50s—and I’m pretty sure that’s how they think of themselves—then Shugo Tokumaru should be a considered an insidiously updated kawaii pushback against the tide of Avatar bullshit and culturally emblematic Pizza Hut/KFC salad bars issuing inexorably from the US into the rest of the world. He’s certainly no less indicative of Japanese culture than his soul shredding brethren, yet he insinuates himself slyly into the crammed spaces left in our fried chicken-engorged hearts. This is how Shugo described Tokyo, his hometown, in a CMG interview in 2005: “Building, people, building…people, building, people, park, building, people…” Adorable. Accurate. Revealing.

Shugo’s a Japanese touch-point less immediately devastating than ol’ Gojira, but probably the more subversively effective for that. He’s Hello, Kitty. He’s Princess Mononoke. At the very least he is his country’s strongest presence in a genre (or the intersection of several) dominated by tinkerers from other regions of the globe. He’s alright with that: “I like to see that. I like a [misrepresented] image of the ideal of Japan that the Western people thinks (sic) about.” But just you Western people give “Karte” a spin, or almost any of the meandering, packed-to-the-brim folk journeys on L.S.T. and try not to think about the dynamism between Japan’s long, deep history and its explosive, bleeding-edge, nearly futuristic modernity.

Yeah, Shugo’s a pusher alright, and an adroit one. Adept enough to hook savvy and discerning CMG multiculturalist Aaron Newell into once penning an open letter to indie labels on his behalf, cajoling them in feverish addict mumbles to “buy or lease this man’s soul.” And here he sits half a decade later, bashfully occupying a respectable position on a list devilishly difficult to compile precisely because many of those other tinkerers had to be pared away from it to rest, still tinkering, on the cutting room floor. They couldn’t front their game like Shugo. We wanted them on the list, but we didn’t need them on the list; they didn’t push us as hard. And here’s the thing: when the drug highlights varied notes, when it surges unexpectedly, when its rushes are restrained and its hushed recesses have the pulse of a hallowed breathing, a pusher is a boy’s best friend.

Eric Sams

95 :: Vitalic

OK Cowboy

(Citizen/Pias; 2005)

If OK Cowboy ostensibly appears uneven, sometimes like the stereotypical, patchy dance album—a vehicle for some slamming club singles with a few skits and downtempo moments thrown in to pad out the running time—when Vitalic’s on form he’s offering up such a ferocious skull-fucking experience that any brief interludes or filler barely seem to register. At the heart of the album are three cuts from the massively influential Poney EP (2001), a release that forcefully injected grimy rave energy back into the glitzy superclub scene at the time and that’s lost little of its power in the subsequent decade. Pascal Arbez-Nicolas’s great success on OK Cowboy was retaining and maintaining the freshness of Poney four years later and across a long player, despite the steady move from outsider to establishment that came with a major release and rabid blog attention. In that sense, the record’s rough edges are part of its indelible, exciting charm; tracks like “My Friend Dario” and “Newman” go straight for the throat in a way that other producers wouldn’t have attempted given similar means and audiences. While OK Cowboy may not sound finished in places, all of its bare wires and splinters contribute to a clear communication of rave’s essence in 2005: more up for whatever than a thousand slickly assembled imitators.

Jack Moss

94 :: Fire Show

Saint the Fire Show

(Perishable; 2002)

Fire Show are often talked about like this ultra-obscure cadre that flitted about on the fringes of the post-millennial post-punk revival; a trait they share with historical precedent This Heat. So rote it’s basically a meme, the story so often told is that core duo M. Resplendant and Olias Nil abandoned the confines of their more traditional 1990s group Number One Cup; recorded an album and a half of material that hinted at genius but didn’t quite give up the ghost; and then recorded this, their masterpiece, before deciding to call it quits—and all of this in the space of about two years. It’s a pretty idea, I guess, but it ignores a lot of things: Brian Deck produced all of Fire Show’s material, and Number One Cup’s People, People Why are We Fighting? reads like an early entry in the post-punk renaissance that just needs to shed its Brit Pop influences. Oh: and the band’s from Chicago. So, y’know, it’s not like they were some crazy mystics producing music in a shack on the outskirts of Topeka.

Rather, I’d say Fire Show’s legacy should be that they recorded the masterpiece of the whole post-punk revival about a whole year early, and got the hell out of dodge before the Rapture’s success would cause everybody to wonder whether the post-punk revival had been a good idea in the first place. It’s that later phase that made everybody think “post-punk” and “dance-punk” were interchangeable; it’s a record like this that reminds us why punk, indie, or whatever the fuck were so important in the first place: that ability of a couple folks to get onstage with a minimum of means—in this case, samplers, strange poetry, and more traditional instrumentation—and make epic fucking rock ‘n’ roll. I’ve heard critics call this thing sedate, but if they think it’s that toothless they must be too numb to feel it biting into their skin and ripping their flesh apart.

Mark Abraham

93 :: Radicalfashion

Odori

(Hefty; 2007)

Hirohita Ihara’s wondrous and sometimes real scary Odori opens childishly: Radicalfashion’s toying with random, clanging nonsense, as if he’s tossing change into a damp sink, and so comes off as if he’s toying irresponsibly with our notions of ambient or noise or what a record with that cover should sound like. But “Opening” is followed neatly by “Suna,” which, like a four year old who loves to sprint down the sidewalk one day eating shit and scraping her little knee wide open, tumbles sourly after two-something minutes of gaily flitting piano, a strange, new sense of paranoia inherent in its pace when the piano does get up, this briefly before the song drops out and melodrama fills the vacuum, grave violins swollen with pain wandering throughout a placeless gray. “Suna” isn’t allowed to skip or scurry without paying a physical price; and, for that matter, there isn’t any visit to the pediatrician’s office afterwards, no cherry lolli for being a good boy or girl, there’s only “Usunibi,” ominous and lonely, a distortion-swallowed scream the one sign of life before even it’s grabbed, retrieved, and drowned by the abyss that mounts like coffee black weight behind the listener’s eyes. In this way, Odori‘s songs seem little more than brief and surprisingly perilous pairs of causes and obvious effects, of adorable, prepubescent melodies running with scissors down long hallways, their parents’ nightmarish stories of impalement and carpet-powered seppuku ringing loudly in their ears. As melodramatic as that sounds given the album’s minimal means—mostly piano, brief strings, and the hushed, ambient ephemera of both quiet studies and condemned, mildewed warehouses, environments Radicalfashion seems to hold in equal reverence—Odori carries an unconsciously pregnant weight throughout, and so even the record’s most playful moments are beset by the possibility of, more times than not, terrible, terrible consequence.

But these are consequences more implied than manifest, like the feeling of a TV’s life changing the pressure ever so slightly, somewhere, but never being able to detect the lit screen. “Shunpoudoh” strays little from its pogo-ing vocal burps and springing piano, but just as the song pitches its head back to let out a squeal of glee, something ominous and screeching slides between bounces. This terrible danger, formless but inevitable, is what makes Odori such a powerful and powerfully simple mass of ambient and neo-classical and chamber pop and drone: Radicalfashion disregards it. And so each song makes the same mistake, every intimacy beset by loneliness, every sweet vocal phoneme cut off by big sonorous gobs of water splatting into buckets in an unused, abandoned waste of space once bustling with activity and progress. Though this is only Ihara’s debut under a—I think, given some thought—fitting moniker, Odori is a vastly mature and masterfully muted experience, a record that ages almost indiscernibly throughout its run-time, but by its end is suddenly, lucidly aware that it’s about to quit spinning. There’s nothing more adult than that.

Dom Sinacola

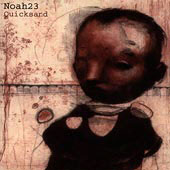

92 :: Noah23

Quicksand

(Plague Language; 2002)

“I’ve done acid three times in the last two weeks / so you might say, I’m on top of my game.” Yeah, Quicksand is one of those records. When listening to this, the masterpiece of Guelph-based artist Noah23, there’s a distinct sensation similar to what you’d feel when reading a paragraph of a sentence from Gravity’s Rainbow or watching one of Cronenberg’s best, the feeling of being barraged by something absurd and delinquently cerebral but still, for some godforsaken reason, resonant. Except that this isn’t a post-modern lit classic or a high concept art film; this is a rap album. Try to accept that and throw lowered expectations out the window.

Noah’s so kinetic in how he collides together all his far-reaching imagery and obscure references that he creates his own heat, his own nuclear wit and black humor. And that heat is absolutely blistering, such little mind does it pay to our sensitive skins weaned on obvious punchlines and, like, coherency. In a way this record is an anticipation of Weezy but it’s also its own Babylonian beast, a singularity trying to come to terms with the nature of its freak existence and completely unable to pass on what makes it so special. What The Cold Vein (2001) is for rap musically, Quicksand is for rap rappingly. Sure, Noah has released really good albums since this one but those feature modicums of polish and restraint—substances antithetical to the sprawling anti-substance of Quicksand. The record title is apt: Noah’s flow is like vestiges of things once thought hard now but a thick, gritty whirl giving way to an abyss. And into this hourglass pit a slew of no-name Canadian producers hurl a heap of lurid dub- and jungle-inspired beats, as if on one record a bunch of niche-given destinies decided to meet. How on “Imhotep” Orphan can fashion a behemoth banger out of the opening to Edward Elgar’s “Cello Concerto in E Minor” while Noah does tragicomic bullet ballet is something that still gives me cold shivers.

But it’s the finale where Quicksand really steps over the edge. You know how when you see a rap track’s near ten minutes long and you just automatically know it’s because there’s a hidden cut or the last six minutes are shout-outro? “The Fall” defies your (and my) assumptions. Like a more unbridled and perverse prototype for Cadence Weapon’s “Turning on Your Sign,” producer Naval Aviator furiously cycles through a fever dream of brilliant beat ideas that ping across like a highlight reel for club music from whatever parallel universe is home to the Reapers in Mass Effect and/or the Sub-Space of Super Mario Bros. 2. Noah sings “all things fall so sink into it” a few times before bearing down with the breathless might of his word-savagery on the only kind of truth he’s interested in, the sort that instantly evaporates once grasped. It’s a powerful statement that music and language are constants but only because they’re constantly transient, and it’s this ever-shifting dimension over which a dissolute manifesto like Quicksand reigns. Kiss the rubric ring of the ridiculoid.

Chet Betz

91 :: Björk

Vespertine

(One Little Indian; 2001; 2001)

Vespertine is Björk’s relationship record; this is strange given how, up until the album’s release, Björk was making her name on an odd innocence somewhere between Peter Pan acolyte and Martian. But, so steeped in wide-eyed guilelessness, nine years on Vespertine seems more and more the logical step from the billowing electronics of “Army of Me” or “Joga” into more intimate IDM, a sign she was up to going knee-deep into the sticky cocoon of monogamy and long-term commitment, that she was ready for a different and differently intense form of surrender. And so there’s the part in the “Pagan Poetry” video where a writhing, nude Björk is so overwhelmed by her incantation of “I love him / I love him” that she doesn’t even lip-sync along for a line or two. All of Vespertine is basically contained in those few seconds.

“Will I complete the mystery of my flesh?” she asks in “Sun In My Mouth,” and it’s a good question to pose: we all have these fleshy urges, so what the fuck are we going to do with them? How far are we willing to go with somebody else in order to figure it all out? The album’s cloistered, glitchy soundscapes seem to reflect the tension between sexual liberation and the emotional nakedness, biblical stateliness even (“Who would have known / A boy like him / Would have entered me lightly / Restoring my blisses?”), required for any successful coupling. Vespertine even, if loosely, sometimes parallels any courtship, from tentative beginning (“Hidden Place”), to unbearably hot idealism (“Pagan Poetry”), to requisite weighty, existential pondering (“Aurora”). By the end, with “Unison,” she’s grown her “own private branch” of the “family tree” that recurs throughout Björk mythology: she “can obey all of your rules / and still be me.”

The similarities Vespertine carries to Björk’s older material keeps this a familiar release, despite the frosty loops and synths or the comparatively mature subject matter. And while less overtly sexualized songs like the Harmony Korine-penned “Harm of Will” (seemingly yet another song about their mutual friend Will Oldham, who’s painted as a foil or sorts, a coy man about town) slow the rhythm of the album towards the end, it’s more of a logical comedown than an actual drop in quality. It’s also not a particularly romantic tone to close on, but yet another touch of sobriety for a striking album that smartly sent a shock through the cutesy trappings that marked Björk’s appeal for so long.