Features | Lists

By The Staff

10 :: Wrens

The Meadowlands

(Absolutely Kosher/LO-MAX; 2003)

It’s tough to make it on thirteen grand a year in the Meadowlands. This past year I had to do it on nine. That’s a hell of a W-2 to look at when you’re about to enter your thirtieth year, your peers and relatives all upwardly mobile, to some degree, many with concomitant families of their own (and bills, and headaches, sure, but when you catch these people—with increasing degrees of fleet, as their own schedules are less open than yours—you can’t help but notice a certain peace in their voices; that their problems are their own, that at the end of a day it all becomes something to call, with pride, a life). Things are dawning on me at twenty-nine that hadn’t before: just because the bar crowd keeps getting younger doesn’t mean I am; those of us who are hanging around are getting quite a bit wider; somehow, no matter how drunk I can get (spoiler alert: pretty fucking drunk) old lovers still aren’t walking through the door; being opinionated is not, it turns out, a marketable skill in New Jersey, nor anywhere else; and the unfinished (or else unappreciated) Great American Album has replaced the novel as the silent drinking companion of the embittered recluse. Rock n’ roll meant well, but it truly couldn’t help telling young boys and girls lies. The problem was I took it seriously.

So excuse me for over-identifying with The Meadowlands, wherein the Wrens tackle all these problems by simply giving up. One imagines Charles Bissel and Kevin Whelan singing directly into their third double of whiskey and ice. “Rural poor and bored, lord, at thirty-five,” sighs Bissel in “Everyone Choose Sides,” eyes popping like an ice cube just read his fortune. “Right. I’m the best seventeen year-old ever.” Whelan, on his right, shakes his head, only half-listening but feeling just as miserable. “Are you happy now?” he asks some phantom in the bar mirror, finding in that reflection the soured realization of the Rolling Stones’ “Happy.” “You got what you want.” He drains his glass: “but I’m over that now.” Bissel nods, his mind turning to “She Sends Kisses,” the landmarks of the South Jersey shore rising like bruises, recalling fucks and kiss-offs in equal measure (and one hell of a final postcard: “Your move. I’m tres involved. Move on. Love, Beth”). “God,” he thinks, catching a glimpse of his receding hairline (and praying, for a split second, that it really isn’t him in the same mirror), “remember when Ann found those letters I’d been saving? My ‘Ex-Girl Collection.’ ‘Happy Anniversary, jerk … is this how men mark time in couples?’” He wonders why the whiskey only makes her voice echo louder.

“I should have listened to them.” That’s Whelan, still not listening as he seethes in “Hopeless,” as much a damning of sex condition as the human one. “Go thank yourself for nothing. It’s all you’re ever good for.” Bissel can only shake the ice in his glass. “I’m caught. I can’t type. I can’t temp. I’m way past college. No back doors.” He watches the ice spin like clothes in a dryer, attempts to add whether he can buy another round and still do the week’s laundry. “This Boy is Exhausted.” And this conversation—or what passes for it—seems to go on for an hour before, suddenly, they arrive at the same point: The House That Guilt Built. “I’m nowhere near where I thought I’d be. I can’t believe what life’s done to me.”

That couplet appears near the start of The Meadowlands, and it’s an appropriate jumping off point. “Exhaustion” is the watchword of this album; the Wrens are simply too worn-out and run-over to attempt anything other than naked honesty, to shoot at anything but the center of the target. Their “Wrens’ ditch battle plan,” as they call it in “Everyone Choose Sides,” while loud, tattered guitars bellow over the mix. You will listen to those guitars even if it kills them, and their owners feel the same way about their lives. “Worked these sands / I won’t go back again … a wasted shot at high-tide heaven … I walked away from more than you can imagine and I sleep just fine.” They give Britt (or is it Ann?) her fair share in “Ex-Girl Collection.” “I’m called ten kinds of bastard,” Bissel sings in a tone that suggests he deserved something closer to seventy. “Fine. Is that all you got?”

This excellence-through-enervation extends to the band’s music. Call it the Rubber Soul (1965) effect; after years of touring and homesickness, the Beatles, tired beyond tired, bashed out some quieter tunes in time for Christmas that betrayed an effortless sophistication, and in so doing jump-started the band’s maturity. So it is with The Meadowlands, only with a seven year gestation period, which turns out benefiting the Wrens. They had the time, resources, and sheer blind talent to make all fifty minutes count. They’ve seen all the fancy tricks, they know what doesn’t work, and they can do what works as well as anybody. Every song is crafted by hand and spit-shine polished.

“The House that Guilt Built” is not only the perfect opener lyrically, but musically it’s a brilliantly executed fake-out. Accompanied by only a guitar and, yes, crickets, it’s such an ostensibly unassuming song that you never see its follower, “Happy,” coming. Starting with a bubbling bass line and a ghostly guitar, we never expect the arrangement to build the way it does, climaxing not once but twice in truly cathartic, righteous pop (think if the Pixies listened to Radiohead, and not the other way around). If there’s a more elegant chord sequence in the past decade than “She Sends Kisses,” I don’t know it. It might be “Thirteen Months in Six Minutes,” a melody as slippery, circular, and painful as its lyric (“this is what I thought: I still seem to be caught. I’m a footnote at best”), reminiscent of the best Red House Painters songs. Odd-metered guitars clang against the beat in “Hopeless,” their chime seamlessly meshing with Whelan’s geriatric New Wave melody, and lending violence to his vocal delivery. “This Boy is Exhausted” is as anthemic a pop song as ever been written, hilarious when considering it not only deals with the difficulties of writing one (“I can’t tell a hit from hell from one singalong”) but of being in a band itself. “I guess we’re done,” Bissel surrenders. “Because every win on this record’s hard won.”

Indeed. From track to track, words to music, conception to execution, each minute of this record is indie rock of the highest possible caliber. There are some for whom the phrase “the calamity of age” will have no resonance. The young, for instance—when I was twenty-three, I found this album too drowsy to merit multiple listening, its production too flat for its structural brilliance (now I love that the vocals are so low; it adds to the basic feeling of triumph through bleakness, that sense of this-is-the-best-shot-we’ve-got-and-we’re-going-to-take-it-so-fuck-it that armors the songs), and those of you who, like my friends, have found a place in this world, who have reconciled yourselves to the basic conditions of life. The rest of us, thank God, have The Meadowlands.

Christopher Alexander

9 :: Subtle

For Hero : For Fool

(Lex; 2006)

Adam Drucker is the best rapper alive. For a second, put aside the allegorical storylines across the Hour Hero trilogy. Backburner the symbolism, the wit and the humour, as well as the patterns nodding to Busy Bee, Ice Cube, and K-Solo. For Hero : For Fool is a clinic in the technical, fundamental “rapper” skills of breath control, cadence, and intonation—a physical exercise. It has to be: it trashes the golden rap rule that in order to sound authoritative you have to be passionate about what you feel, write it down, and then rap it like you couldn’t care less. It fucking hates that rule. Drucker’s passions for breath control, cadence, intonation, race, relationships, the political history of hip-hop music, average kids and their too-average idols, and how easily passion can atrophy without exercise, herniate this album. He wrote them down in a language of guts, blood, apes, and caste systems. Just because the people he respects would notice, he stitched each syllable into a drum hit, then rapped them like he was eradicating poverty, hunger, disease, and the Clipse with each exhale. And he did it while still making you feel—deep down in your Raider-hat-wearing heart—that he would be fine with shooting, stabbing, or selling drugs to you if you tried to fuck up his flow. As we now know after Group Home, Shape Shifters, and Aesop Rock, there is a correlation between how good the rap sounds, and how much artsy shit people are willing to tolerate in that rap. Drucker bled himself dry over an “important” guitar-driven allegorical hip-hop album featuring a game show where the contestants measure their entrails between commercials for celebrity blood transfusions. And it’s one of the best albums of the last decade. He is the best rapper alive.

notextile.

Aaron Newell

8 :: Microphones

The Glow Pt. 2

(K; 2001)

I’ve told myself, at least once every year since Phil Elvrum shifted paradigms from the Microphones to Mount Eerie and added that extra “e” to his name, that I would never again write about Phil Elvrum. Probably within the forty minutes I spent on the phone with him back in 2005, which was soon after I spent God knows how long trying to get a grip on the thematic beast No Flashlight sold itself as, I realized, when Phil spoke the following words, that a lot of my effort was futile: “…because reading the reviews it’s like every single time, even if it’s positive, it’s just off. I don’t blame people for being off at all, I know my albums are confusing. They’re confusing to me, too. It’s just, um, a special kind of terrible feeling reading something that’s so off. It’s something I’ve tried really hard to be clear about.” When, following this review and Elvrum’s opening the doors of P.W. Elverum & Sun, the musician released everything stored within the papier-mâché vault of his artistic ambition while making manifest seemingly every whim at his disposal, I prepared to give up; as his folklore bloated in incomprehensible directions, why should I continue figuring it out when, as had been so succinctly pointed out to me, I will always be off?

Because of The Glow Pt. 2. Comprehensive, pulling to its chest a scope hushed (“I’ll Not Contain You”), delirious (“The Glow Pt. 2”), narcotic (“The Moon”), devious (“I Am Bored”), and nakedly exhausting (“Samurai Sword”), the album, arguably Phil Elvrum’s finest hour, is both saturated with the thematic conceits that would subsequently envelop everything Elvrum released and, fortunately, divorced from the brutal task of divining what Elvrum was all about at that point in his splayed-out career. Here, he’s straightforward, declaring facts about what the Microphones are doing and what Phil Elvrum is, or desires, subtitling and hypertexting every gesture, sound, or emotion—“I Want Wind To Blow,” “I Want To Be Cold,” “I’ll Not Contain You,” “(something)”—as if clarity is an imperative in staying afloat amidst the guile of album-making and musician-ness. The Glow, if it hasn’t been drilled into your psyche by now, is decidedly “lo-fi,” as purely as that term can be digested, a record of simple, inexpensive means stretched to fill the responsibilities normally supervised by cadres of instruments and small countries of musicians. At least in theory: where lo-fi has come since this record’s release is almost meaningless, but back in the days of yore, Elvrum was demonstrating “lo-fi” as the functional bridge between the hugeness of alternative rock (the ostensibly limitless resources of radio pop and the cosmic spit-length of Radiohead’s burgeoning world-rule) and the immediacy, even accessibility, grunge left behind when the word became more groan than buzzed. (And yep, Elvrum’s from Olympia, WA.) The Glow Pt. 2, then, is that piece of architecture canonized, an immense, self-contained testament to elephantine aspirations held breathlessly within mousey every-people.

Though joined by typical collaborators like Khaela Maricich, Kyle Field, and Karl Blau, and by no means a point of finality to the tenure of the Microphones in Elvrum’s grander career arc (Mt. Eerie [2003], the Microphones’ final album, would be bigger on all possible fronts), the group’s penultimate release is too magnificent in its execution to not pick apart in harrowing detail—word by word; indiscernible sigh by indiscernible sigh; violent thrush of reverb by violent thrush of reverb. Even in its opening moments, The Glow is nuanced but revelatory: check four minutes and twelve seconds into “I Want Wind To Blow” to witness the single guitar mostly drop out, drums replacing the mostly innocent strumming, spaced martially and leaden with portent; check fourteen seconds later to witness one galloping bank of fuzz render the song a mountainous feast. This alone sold me, years and years ago. Only these fourteen seconds, and, since, I’ve been a relentless convert, since I’ve poured through Elvrum’s special editions and side-projects and one-offs, looking for the key to how that brief period of a long record could so engender in me feelings that still to this day give me shivers, that prompted me to—when driving into the Columbia River gorge over a year ago, ready to begin my new life so far away from the Midwest and Chicago and everything I knew—play that song, loud, and watch as it opened up the Pacific Northwest, sliding backdrops apart like the extravagant dressing on the stage of a high school play, to tiny, insignificant me. Whether I’ll be rewarded with closure or not, I press on, waiting and vigilant, hoping someday soon, someday in the next decade, Elvrum will finally tell me why I love him so; until then, I’ll content myself with being blissfully ignorant.

notextile.

Dom Sinacola

7 :: Radiohead

Kid A

(Parlophone/Capitol; 2000)

Sigh. Um: Kid Fucking A? What, like I’m gonna use this blurb to tell you that “Idioteque” and “Everything In Its Right Place” suddenly suck? No, it’s still a life-changing record, but maybe not for the same reasons it was when it was first released. This I’ll get to soon enough, but first I’d like to write about beer.

In the realm of obsessive acolytes, experience has told me that beer geeks are close cousins to Radiohead die-hards and Stephen Malkmus fans in their use of breathless hyperbole and undying devotion to the cause. I’ve seen fist-fights break out over the merits of Russian Imperial Stouts, generally amongst big, hairy guys that are usually drunk at the time. I’ve seen similar violence erupt over the time signature in “Pyramid Song.”

So: there’s this brewery about an hour north of San Francisco called Russian River, which is responsible for what I consider to be the greatest batch of Belgian-style Sour Ales in North America. But its crowning achievement, the thing which gets it discussed in hushed tones, is “Pliny the Elder,” a Double India Pale Ale named after the Ancient Roman naturalist credited with creating the botanical name for hops (of which this beer contains legions).

It’s gotten to the point where “Pliny” is now viewed as the shining bastion of beer integrity against which every other similar beverage must be judged. It won a gold medal for Double IPAs at the 2006 World Beer Cup (and yes, such things do exist); it’s completely unavailable on the East Coast due to distribution issues and concerns over freshness. Unscrupulous individuals camp out by the brewery near release dates so they can be first in line to load up multiple growlers and then scalp them to the public on beer websites. It’s a beverage that’s created an unwavering line in the sand, a “with us or against us” proposition: you’re not allowed to dislike lest you risk ridicule amongst your peers. The legend has outstripped the reality.

Being a bit of a beer nut myself, I’ve had Pliny on a few rare occasions, and there’s no question that it, like Kid A, is indeed very, very good. It’s smoother than Michael McDonald in a genre not known for easy drinking, with a nose of fresh grapefruit and a delicious piney tint. That it’s a quality product really isn’t in question. But at the end of the day, once the drunken glow dissipates, it’s really just a good beer, and Kid A is just 40 minutes of excellent music.

Actually, that’s not entirely fair. It helps to understand the musical landscape in 2000. Still in an era where album leaks were virtually non-existent and the preferred method of listening to music involved purchasing “compact discs” from a “record store,” Kid A arrived relatively shrouded in mystery. OK Computer (1997) was a completely justified breakthrough that forced everyone to reconsider why they slept on The Bends (1995), and then, as the new millennium began, Thom Yorke was promising a guitar-less follow-up record that would alter the public perception of Radiohead and that of popular music in general. For reals. No advanced copies were released, the hype so intense fans were more than willing, eager even, to do things like pay to listen to Kid A soundtrack a completely unrelated aquatic life movie in New York City’s Lincoln Center a few days prior to its release. These fans would be hearing the album in full amongst their peers for the first time, a now completely antiquated notion that Radiohead briefly revived with the online announcement and next-day download of their recent In Rainbows (2008). It was the most eagerly anticipated follow-up album since In Utero (1993).

Kid A was ahead of the curve as being one of the first major albums to actively “leak,” though not even remotely on a scale comparable what we now take for granted. Instead, people feverishly anticipated Kid A for months, actually had to buy it, and then got to experience the now nostalgic rush of taking that record home on October 3, 2000 and listening to it for the first time alongside millions of other fans doing the exact same thing. And that it turned out to be a murky masterpiece exceeding people’s wildest expectations didn’t hurt. If OK Computer solidified the idea that there was, unquestionably, life after “Creep,” Kid A signaled the ascendancy of Radiohead to arguably the most important band of its generation. It is, by definition, a milestone. And ten years later, we know this really isn’t up for debate: Kid A would be far from what anyone would refer to as a feel-good record, and yet there are very few situations in one’s life that cannot be made substantially more enjoyable by its presence. Not unlike Pliny the Elder.

David M. Goldstein

6 :: Clipse

Hell Hath No Fury

(Re-Up/Star Trek/Jive; 2006)

All adulatory ink spilled over Hell Hath No Fury is true as math. The Neptunes alternately expand and distill their aesthetic into an aural substance so trill the radius for contact highs spans entire city blocks. The Clipse operate with a punctiliousness attributed to Olympic gymnasts and NASA employees. One and one is two, it’s as simple as Blue’s Clues. Thus, I won’t parse the equation; rather, I’ll reflect upon the equal sign. The first eleven tracks of the Clipse’s opus feature the Brothers Thorton satiating our steep expectations, adeptly fleshing out conceits hinted at on their debut and subsequent mixtapes, all unflinching vigor over relentless heat. These 44 minutes of revelry would have quieted even the most violently growling stomachs; I would imagine that truncated version of HHNF still cracks our top 20.

But Hell Hath No Fury is 49 minutes, and holy fuck are the last five crucial. “Nightmares,” the twisting salve that uneasily ties this inextinguishable masterpiece together with frayed twine, transforms HHNF from scorcherous exhibition to one of the most complete, self-contained album albums of the decade. Without it, the frenetic pace of the eleven tracks that precede it would go down like smoldering gravel. It is the glass of water after eleven shots, the goodnight kiss after 44 minutes of furious copulation, the haunting ballad for which the Clipse’s definitive statement aches. Unlike anything else in their catalog, it is a song-length admission of humanity. While much of the Clipse’s work posits them as conflicted villains, this just sounds conflicted, dripping of nightsweat as the sword of Damocles hangs from the ceiling above their California kings at the Delano. It concludes an exhaustive lyrical performance, logically, with exhaustion. And a warning: “hope your body’s got strong kidneys.”

The Clipse have since moved forward. Or rather outward, like a tangent from a circle. As is their wont, they’ve dropped a couple great mixtapes rife with vociferous punchlines; as their corpus grows, Pusha’s case for GOAT grows stronger. Much of Til the Casket Drops explored “lifestyle music,” their interpretation of club rap—perhaps a stab at commercial viability—that tasted like a swig of sour milk to most in the considerable shadow of this behemoth, but think for a moment: like, almost anything would. So be thankful for “I’m Good” and “Popular Demand”—they’re a lot of fun—and remember it took the Clipse four years to fully hone their aesthetic, graduating from Neptunes protégés to sneering peddlers of their own personas. They might find a way to make club rap resonate in ways unanticipated. For now, we have this splendid document: the rap duo of the decade peaking in concert with the decade’s best production team. Throw it on the scale, feed ya goddamn self.

Colin McGowan

5 :: Wolf Parade

Apologies to the Queen Mary

(Sub Pop; 2005)

The evolution of Wolf Parade’s affair with Cokemachineglow begins in 2005 and has its terminus here, with me—I’m a Krug man myself, nice to meet you. It’s a vibrant and functional liaison we’ve carried on over these past five years, birthing some of the best obsessively thorough writing this site’s seen (as Mark so efficiently implies, we’ve been fucking this shit up for breakfast), as well as a number one album, a title we seem to share with the band, as if it’s as much theirs as it is ours, us so clearly recognizing the special feat a young band had accomplished. We’ve all had our say with this band at some time or another, in some form or another, until, when rumors of the inevitable breakup sprouted with vehement haste last year, we realized, as a CMG community, that its inevitability was in no small part our fault. (Or Jesse James’s; what with his recent Sandra Bullock cheating on the Queen Mary, Wolf Parade’s antics are shamefully small potatoes.)

With Apologies to the Queen Mary, the mythos of Wolf Parade was established: one half Dan Boeckner, paladin in his traditionalism, earth-borne but quietly magical in how he surreptitiously places his knight’s colors at the foot of his obvious influences (Springsteen, yes, and also New Order); the other half Spencer Krug who, like Jeremy Irons in Dungeons and Dragons, chews scenery while sweating profusely, jaundiced, grinning through brown teeth, as if the magic within him is inhuman, bound to kill him as it climbs toward its ultimate potential. As critics, we didn’t offer any palliative for the obviousness of the band’s division; not that we should have, Apologies so clearly marked with “Dan” songs and “Spence” songs that differentiating between the two becomes a reflex inherent in any fan worth their weight in free Moonface EPs. But, as Mark again pointed out when covering the band’s unsurprisingly excellent follow-up, “That’s the crux of Wolf Parade’s assault on the modern condition: no matter how active you are on the fringes, your activities get filtered through successive levels of hierarchy until they become either/ors.” In other words, this is how we must deal with the strange might of this band: in multiple choice, in black and white, in love and hate.

Because, hardly bent upon the crease separating Krug’s world from Boeckner’s (their foreheads almost touching, like boxers shirtless before a press conference crowd, before being weighed, just staring deeply into each other’s glassed-over eyes, consumed with thoughts of rage and also of madly French kissing), Apologies to the Queen Mary is the ultimate in mid-00s iceberg minimalism. I see a swarthy line from The Moon and Antarctica to this, a line whose A is an unaffected indie rock band exploring the logical expansion of their sound, and whose B is a band with all the makings of bombast speaking laconically, in terse gestures and proprietary spaces, helped along by the one man from point A who knows all about concision and ambition and the grey estates between. Apologies is the glacier’s pin-prick apogee and what’s submerged beneath is the astounding weight of two lives, of father issues and sexual identity and rewriting one’s own history, covering one’s own art, of the starkness inherent in the album’s startling opener as it makes “This Heart’s On Fire,” the album’s last song, a warranted handshake with everything fat and dripping “You Are a Runner and I Am My Father’s Son” isn’t. And so, in 2005, in the middle of this decade we’re celebrating, that we’re attempting to take as one complete symmetrical arc, the gap was closed between where indie rock had been and where it was thrust, eye’s bloodshot and fingers bleeding, since “indie rock” became a viable way to describe what you can infer (care of the same bands I’m using the term to qualify, natch) I’m describing. Exaggeration or not, real or imagined, this is the feat CMG got behind: how Wolf Parade, in under 50 minutes, trapped the intractable angst of an intractable time in white-boy rock (not to mention—seriously, we may have gone this long without mentioning—how in less than four years 9/11 was still as confusing as ever for those of us at its fringes) with equal measures respect, restraint, and a low-lidded jones for bursts of wailing poignancy. (We’ve been over this before, but five years later, “Give me your eyes, I need sunshine” squawking magnificently out of Spencer Krug’s mouth is still…orgasmic, intuitively intimate but applicable to what we should be squawking about in 2010—a demand to get out of our heads and embrace a better perspective.)

Of course, Wolf Parade hasn’t broken up; in fact, they’re a horseman tail’s hair’s breadth away from embarking on a tour of Canada and Europe. Fans collectively wipe their brows. Still, it’s easy in the aftermath of the band’s debut—seemingly (as in: with our hearts, we deduce) hundreds of records later—to not feel the least bit responsible for the prolificacy of the band’s two songwriters in the interstitial spaces between albums, acclaim, tours, and brunch at Isaac Brock’s compound. Every artist on this Top 100 has somehow influenced each CMG writer to spend this much time in protracted revelry, to consider why and how such music has taken such tolls in our lives. This (sorry, Lindsay) is the best indie rock record of the decade; its tolls are incalculable, its reach insurmountable, and, as involved as we are in its spreading, its multiplication—its klaxon call for more records to be just like it, to be so balanced, intelligent, prosodic, both devastating and subtle—we can’t be blamed too hard for taking a bit of pride in the band’s now-universal, Urban Outfitters appeal. Kiss the ring, Krug.

Dom Sinacola

4 :: Erykah Badu

New Amerykah Part One (4th World War)

(Puppy Love/Universal Motown; 2008)

I think I can say without any real profanity that New Amerykah is some holy shit. Not to come off as vain or overly self-convinced, but if I could regurgitate just one line from my original review: “In every which order I could put it: Badu is people is hip-hop is god is nation, the title of her work grafting her first name into this country’s.” Here we are a couple years later and I stand by that review while also feeling the record’s importance still ballooning for me, still floating higher and higher. Part II is imminent and it’s a bit scary because I’m afraid that, like somewhat happened with once-CMG-darlings Future of the Left, it will be the sort of follow-up that accentuates fatal flaws in the core approach and so casts a shadow of doubt on the worth of what previously seemed so special and awesome. But the first single off Return of the Ankh, while not completely party to what I love so distinctly about the first New Amerykah, does have me convinced enough to say, yes, Erykah, I am ready to jump up in the air and stay there. Plus, like “Honey” all over again, it’s just a bonus track.

Nonetheless, I’m jumping because—despite slightly club-skewed production and a gonzo Weezy F. Baby cameo loudly lip-smacking then munching away at any semblance of sanity—the track’s sentiment is so true to the magnanimous philosophy of Part I that I can almost hear the otherworldly scale of the Yamasuki Singers sample* from “The Healer” in between this banger’s thudding drum kicks. About forty blurbs ago Colin was talking about kindred 2008 record Tronic (good God, what a year that was for mid-major hip-hop! It’s like this year’s NCAAs), claiming in his opening that “Rap’s uniqueness as a genre emanates in principal from its sport-like structure, which facilitates and nearly necessitates competition amongst its practitioners. The genre operates like a small high school, made smaller still by the omnipresent tentacles of the internet, in which everyone is up in everyone else’s shit.” In practice and for the overwhelming majority of the time, this insight to the paradigm holds true. Which only makes it that much more to be cherished/lauded/revered that Badu (granted, not exactly rap, but stick with me here) transcends that paradigm in the service of something greater. Colin acknowledges these rare exceptions, stating for an example that “Madlib seems content to roll spliffs and chop jazz loops in his basement without a care in the world.” Oh, hey, guess who produced “The Healer.” I’m pointing my finger at Colin right now, giving props for the spontaneous set-up. That’s what you call an alley-oop.

Unlike Madlib, Badu actively addresses this issue of equality and presents the solution as metaphysical—even a tad astral but still simple and direct. What’s kind of crazy is that the “solution” is hip-hop, something responsible for both Ice Cube and the ego-centric black hole named Kanye. In “The Healer” the mantra is that hip-hop is bigger than religion, the government, you, me, a Big Mac, etc. But this is not describing hip-hop as the forum for Cam’ron to do Youtube beefing in front of his pool or (I’m calling it now) 50 Cent to buy shares in the companies behind the record labels of the rappers he loathes (a.k.a. all rappers) and wants to ruin. Badu’s talking about hip-hop as an idea; a good idea is “bigger” and ultimately more powerful and lasting than institutions, even when institutions are the instruments of good ideas.

So it is that New Amerykah sounds like hip-hop not in its most institutional form (i.e. a Diddy verse over a Scott Storch beat) but its most conceptual and spiritual. Dedicated to Dilla, this record is the only one that I can think of besides Donuts (2006) that takes a deep understanding of the amino acids that make up hip-hop’s primordial ooze (oral story, blues, jazz, soul, funk, early electronica) and then has fun playing God, re-evolving that basis into what hip-hop could and maybe sometimes should sound like in this millenium. Badu’s music here is as dynamic, fluid, and teeming with life as a river rushing towards the ocean, a channeling of an entire genre’s substance back into the vast expanse of its inception. For a mode of music where the mainstream idea of current often comes down to dumbly slick futurism, this revisionism sounds like true progress. What then takes this beyond just a stylistic triumph is that Badu is a genius songwriter, through and through, from the orgiastic entendre tangle of “That Hump” to the unfolding theme development of “Me” to the both chilling and uplifting long-form elegy that is “Telephone.” In each instance there is only song yet there is only aesthetic—both are so complete that they are forced to inhabit the same space and become one. 8 may be my favorite record of the decade, but the last time I heard this kind of utter obsolescence put to the supposed dichotomy between deterministic form and eloquent content it was in my favorite record of all time, 1991’s Laughing Stock. On top of that Badu’s also got the balls to leave no worthwhile experiment undone while also possessing the wits to leave none of it un-integrated; “Master Teacher” has a split personality which seems complementary unto itself and the rest of the record, emphasizing again this notion of hip-hop as a means of celebrating disparity while bringing to that disparity a sense of wholeness.

In terms of my personal experiences as a 28 year-old music lover, New Amerykah is the first hip-hop record I’ve encountered that is so proudly rooted in a background very different from my own while yet still I feel absolutely no divide between it and me. It’s with a profoundly disarming sincerity that New Amerykah welcomes all of us in, Badu soaring with the flight of previously subjugated culture now free to invest openly in its own cache and her doing so as a way to “know thyself” (often expressed in hip-hop through the stream-of-consciousness rhythms of rapping but in this case Badu’s unique flow-singing) and that in turn as a way of finding communion with the entire diversity of others (samples, heavily influenced instrumentation, multiple producers, guest raps, posses, collectives, networked mythologies [like Wu] that enable the careers of some cats [like Cappadonna], and, irresponsibly, that one time J5 did a single with Dave Matthews), which then in turn brings us to the universals (“One Love,” “B.I.B.L.E.,” “Telephone”) that connect us all to what the record’s liner notes call “the Most High Freaq. The Original G. The Author of the Story. The Time Keeper. The Mother/Father-Rhythm duo. The All-Knowing One of Oneness of One 10101…the Nothing, the Everything, Breath of Life…”

When you really think about it, that’s what hip-hop in its purest essence is all about. Holy Shit, right?

(*Thank you, reader Jezy Gray! Isn’t it great to have a record we can obsess over?)

Chet Betz

3 :: Cannibal Ox

The Cold Vein

(Definitive Jux; 2001)

The Cold Vein isn’t an album: it’s a prophecy. The haunted dystopia Vast and Vordul describe is mystifying until you realize they’re discussing New York—then the wonder transforms to disquiet and begins to claw at vital organs. Two integral components of the city’s robust skyline dissolved into a heap of rubble and bodies roughly five months after The Cold Vein‘s release, deflating the city like a pair of collapsed ribs puncturing lungs. That horrific event and the subsequent despicable decisions of the US government prompted sentiments that permeate Can Ox’s lone full-length. On “A B-Boy’s Alpha,” Vast intones, “My first fight was me against five boroughs” as if he’s been fending off assailants ever since. The two disenfranchised MCs saw New York as a hellscape long before smoke billowed from the World Trade Center; Rudy Guili never really gave a fuck about a “mooley” before or after. If mass disillusionment was a symptom of 9/11 and its fallout, Can Ox’s lone full-length was ahead of its time in ways not initially apparent.

But hold that thought, and press rewind: it seems like a mere twinkle in Chali 2na’s eye these days, but the indie rap boom was an actual occurrence, and The Cold Vein was released in the midst of its furious apex. Def Jux was better than Def Jam, Madlib and El-P were playing jump rope with the boundaries of hip-hop production, and Del, who released indie touchstone Deltron 3030 in 2000, was prominently featured on a single that hit #14 on the charts and was seemingly on MTV every half-hour (to our under-12 demographic: MTV used to stand for “Music Television,” and singles are like really long ringtones). Which isn’t to present a revised history or indulge in facile nostalgia: 2001 gave us The Blueprint, Miss E… So Addictive, and Aaliyah, too. But in the early ’00s “independent hip-hop” wasn’t synonymous with Talib Kweli-eqsue acapella freestyles yet; it stood for forward-thinking rap too eccentric for the suits at Clear Channel, the perfect drug for hopeful endurers of the Shiny Suit Era and kids like yours truly, bred on my older cousin’s collection of classics: De La, Wu-Tang, et al.

The exact historical point this optimism and faith in the validity of indie rap as an engaging counterargument to the mainstream dwindled is fuzzy, but the subgenre had grown markedly stagnant by the middle of the decade, a handful of resplendent fireworks giving way to steely silence, and a generation of listeners, presently ardent fans of Lil Wayne and the Clipse, aged and now smirk at the naïveté of their former selves. While myopic adolescents like myself grew bored with this increasingly minor movement, feigning apathy like we never cared that much anyway (we did), the adult world became frightened, then cynical, then bored as we. And so an uneasy model of non-progression existed: boredom with toys to boredom with, like, the world.

Which: the world can be boring if you look at it ass backwards. In the same manner The Cold Vein isn’t fundamentally new so much as an awesome continuation of musical ideas posited throughout the ’80s and ’90s, and 9/11 wasn’t our nation’s first brush with awfulness, since starving children, drug addiction, and homicides are pretty fucking awful, too, and they’ve been a plague upon us for centuries. Vast and Vordul’s bars argue that the deception of the Bush Administration shouldn’t have shattered our faith in government, but rather augmented our already-immense distrust. They’ve been bored with the government fucking them since the days of Coleco. And yet they overcome that tumult. This tremendous record is lightning kinetic, buoyed by a profound love for their craft and an unsquashable hope. The entirety of Cold Vein exhibits that unquenchable thirst to spit sixteens that vibrate reality, but the final act contains both “Pigeon” and “Scream Phoenix.” The title of the latter has obvious implications and the MCs ride a buoyant guitar lick adroitly, but the former evokes what I imagine being saved feels like. Not the bullshit kind Evangelists claim to have undergone at age eight, but being saved: from the rigors of existence, from anger, from fear; to be literally delivered from evil, an ethereal glow encasing one’s body like pain-proof glass.

From within that glow, I relent: we formerly tittering youths have grown, in our clumsy way, into a fledgling hope like an older brother’s sweater, investing our fragile, regenerated trust in a charismatic Chicago politician, migrating to cities to pursue our lofty ambitions—which we mask in stoic irony, but they’re there beneath the obstinate walls we’ve erected. In our best moments, we’re not that bad. Rap has been great the last few years; the internet has transformed it back into a refreshingly populist genre, bringing mainstream and underground together like Pangea. That charismatic Chicago politician mercifully applied his signature to a tolerable healthcare bill, concluding a full year of governmental gridlock (baby steps, America). And from within some timeless ether, El-P pulls an alternate-universe version of the Bomb Squad through a wormhole. Vordul channels Raekwon’s free-associative, slang-heavy style with brilliance. Vast blesses the mic hummingbird style. All this carnage and perseverance delineated by a temperamental white guy and two antisocial rappers from Harlem who never claimed to be anything more than rats with wings. But is that not all it takes to fly?

Colin McGowan

2 :: Ghostface Killah

Supreme Clientele

(Razor Sharp/Epic/Sony; 2000)

– 1 –

The other night I had this sequence of dreams so vivid and interrelated as to be narrative: themes and character arcs, specific dialogue volleys, careful scene structure, all framing a loosely supernatural horror story about three men killing a fourth while in the woods. I don’t know where it came from; it just emerged fully formed from my sweaty pillow. Things transpired in a sort of timeless cabin, and the woods were Ohioan but bizarre, with whispers of monsters. In the darkness of a nearby barn a centaur pieced together steel for some infernal contraption never seen; he ruled with a quiet authority over the forest’s other beasts, the wildest and worst of whom were the three men themselves. In the end he refused to help them and returned to the soldering and smithing of his shadowed machine. I have no idea where this dream came from, and by the time I reached work the next day, I had no idea where it went. The intricacies of the plot disappeared with the night’s sweat.

- 2 –

The thing is, I don’t really even like Ironman (1996). It’s not in my top five first-generation Wu-Tang records, after the group debut and solo turns by GZA, Method Man, Raekwon, and ODB. A track like “Camay,” where Ghostface spits at length over a leisurely blunt-burner, shines; elsewhere he feels too eagerly packaged as “the soulful one” for my taste, working mostly as a so-fresh contrast to the nightmarish abstractions of his bedfellows.

But I fucking love Supreme Clientele, and always did. It didn’t have to be a classic, maybe shouldn’t have, logistically, trickling out a few years after “Triumph” stopped banging and into an era of totally lackluster Wu-Tang efforts (Tical 2000, anyone?). My first exposure to it was on TV after track practice, flipping between TRL, 106 & Park, and Toonami. It might’ve been on any of the three that the video for “Apollo Kids” was being debuted. I had never heard rap so grand but so direct before, the beat phasing between the horn blasts I loved on Moment of Truth (1998) and the string-laden theatricality of Internal Affairs (1999). The video was all shoes and industrial surfaces, and while I had no idea what the fuck this mink-stoled man was saying I heard in him a confluence of the staggering cockiness I found in Jay-Z and Eminem and the dense, intellectual musicality that made the Roots’ “You Got Me” and Black Stars’ “Respiration” two of my then-favorite tracks. It was somehow both more rambunctious and more sublime than all of that, though, as wild as any of the punk-rock I was still shearing off my CD collection, but decidedly—almost aggressively—hip-hop.

Three years later, I’m a freshman in college—listening, at this point in my life, exclusively to Wu-Tang’s first record. I start to piece in the solo records from my roommate’s collection, eventually picking up a used copy of Supreme Clientele for five bucks from a used record store uptown. The record sprawled, befuddled, banged infinitely. I would think the track was skipping, and then Ghostface would start rapping over it. I’d think there was a hook, and it’d be a half-assed outro. On “One” the beat became part of the raps; on “Woodrow the Base Head” a skit boasted the quotability and huge drops of a single. Whenever I dug into the lyrics I came away more confused than I was before, eventually discerning that here was an entire recalibration from the old Wu-Tang language bases of five-percenter mythology, kung-fu flicks, and New York name-checking. That code I had worked hard to decipher didn’t get me in here. At some point, I got sidetracked from its intrigue.

I have since grappled mightily with the emcee’s output. On a personal list, The Pretty Toney LP made my #11 spot of the decade—with Purple Haze, it explores a post-Blueprint idea of mainstream rap as a forum for wildly idiosyncratic self-actualization, something Wayne would later take a lot from. But I’ve decried at probably too many opportunities the “goony self-caricature” created on Ghosface’s four records thereafter. He is an increasingly sour emcee, trafficking in bogus and mostly boring stories about cumshots and stick-ups, getaways and whoopsy-daisies. Nothing has diminished my affection for Supreme Clientele, but the harsh, ugly cocaine fetishism that has come to dominate his ouevre only looks less and less interesting when compared to the earlier triumph. At times they seem to be the work of a different person altogether.

- 3 –

This one time, in a flash, I thought I was “getting” Supreme Clientele. Like, completely. The logic worked, the stories and reference points made sense—clearly, a lot of drugs were involved. I had just moved to Chicago and was working in a shitty upscale restaurant full of miserable people at the time, feeling generally bad about everything, and working day-after-day to get through Ulysses as if conquering chapters of that might lend a steady measuring stick for the days that rushed unchecked by me. In a fit, I ingested a pile of drugs one night, and at peak their properties were hallucinogenic. When Ghostface announced into a hush that this rap was like ziti I stood in the canyon into which his words fell, and when they crashed high-speed into “strawberry kiwi” that canyon turned Technicolor. Or was this a getaway vehicle? I had found, like Stuart Gilbert’s essential study of Ulysses, the skeleton key: the code that had eluded me. I thought about writing it down while I floated around my pitch-black bedroom that night, thought about grabbing these principles from the air and committing them to paper but of course did not and of course as soon as I woke up the next day and as the night’s residue drip-dried off my spinal cord so too went that essential understanding I had reached with the album the previous night. At first I still saw the shapes, but then even the shapes faded. I remember now only a feeling of certainty as I bobbed around my kaleidoscopically hot apartment that night, followed by a particularly rough shift at the restaurant the next day.

- 4 –

There is a lot of insecurity for some people when listening to rap music, in that much of it is very coded or low-brow or both. Something like, say, OJ Da Juiceman requires a good deal of foreknowledge to properly enjoy, and while the infamously inscrutable Supreme Clientele seems like the epitome of this it is the exact opposite. It sits atop this list (rap-wise) because it is a great leveller. You don’t need to know about New York or Wu-Tang or Mathematics or even mathematics to get this record, because you’re not going to get this record. Even its tracklisting and liner notes are skewed to obfuscate. Like Kid A, which a lot of people think should top a list such as this, it is unfeelingly abstruse, and so somehow a reflection of this era; unlike that record, it is a whole lot of fun. It is still a Friday night rap record, soulful and body-moving and funny.

If I had to describe Supreme Clientele in a phrase, then, it would be as a syntactical playground, where individual words don’t matter so much as the way Ghostface darts between them. But a larger metaphor may also be in order. Pushed out as these words are by the thousand here their array takes on the feel of a star chart, with individual lines serving as constellations drawn among them. Thus the English language is treated as the cosmos—Joyce’s “heaventree of stars hung with humid nightblue fruit”—and we sit as kids on a clear night marveling at their density, their beauty, their luminosity and age. The simplest of these shapes pulled from the sky involves the brightest stars, like when on “One” Ghost pulls a line from the North Star to his very neighborhood, spitting at a mic-trembling holler, “The Devil planted fear inside the black babies / Fifty cent sodas in the hood, they going crazy.” On a track like “Nutmeg” the diversity of effect is closer to a laser light show: “Olsive compulsive lies flies with my name on it / Dick made the cover now count, how many veins on it / Scooby snack jurassic plastic gas booby trap,” and on breathlessly forward. Elsewhere he subsumes whole verses from Rakim and Divine Force, but the words seem like his, too: memories, older shapes traced in the sky as the linguistic display stretches into its second half, turning ramshackle and various. The topics may remain fuck-you or fuck-her or whatever else but on Supreme Clientele rap’s common tropes are a means to an end, a telescope that brings our eyes closer to the sky. What we are actually seeing is much older than rap, although—composed as it is of stars—this shit is still as hot as the sun.

Because ’00s rap had only to challenge what came before it, crystalline as Ready to Die and The Low End Theory and Aquemini were. Badu used its elements as the tools for a ’70s-worthy soul album, Jay-Z and Kanye doggedly pursued its synthesis with pop music, Cannibal Ox and the Clipse found the genre’s common lineage with experimental and electronic production—but Supreme Clientele, atop them all on this list, is defiantly hip-hop. Just hip-hop, rather: just sad guitar and soul samples, well-chopped drums, just dudes rapping and occasionally singing. Ungilded, opaque: hip-hop, street raps. The skit “Who Would You Fuck” is exactly what it sounds like. That it knocks hard front to back—“Wu Banga 101” arrives at track 18 of 20—isn’t the point, because every rap album on this list does. There is, obviously, something else at play here, to have reached across the staff’s many tastes (only some rap-centric) to land here, second only to an album that contains all our tastes at once. Supreme Clientele is completely hip-hop, but it is also bigger than hip-hop.

And—queue Dead Prez beat—what’s bigger than that?

- 5 –

My dream the other night was something, I don’t know what. It felt more substantial than my typical flights of fancy, which have grown infrequent as I’ve gotten older, or my typical dreams, which are uninteresting assemblages of professional anxiety and half-remembered relationships. I believe if captured accurately though the dream’s story would’ve been one I want to tell, conveying truths I deeply believe (that humans can’t outgrow their animalistic nature) in an aesthetic that resonates with me (that is, horror). But I’m not a fiction guy—I let it slide, wrote a concert review instead. My point is not that I am special, or that that dream was special. My point is that while I don’t know if there is a God I do know that story didn’t come from me, fully formed and complete of itself, and that wherever such a dream came from—a rush of inspiration shooting through my neural channels and coming out in a manner unique to my tastes—is bigger than me. Bigger, as it were, than hip-hop.

What resonates with listeners about Supreme Clientele is the sound of a man animated fully by this lightning—composed of it, his voice trebly with electricity, explaining the contours of each electric flash in the language that works for him, the stories that work for him. He’d tell those stories again later but not suffused with such wild and joyous inspiration, sounding not so much struck with inspiration as in complete communion with it. The record is a singular triumph, but it is also an individual one: Ghost’s alone. The rabble of producers, label interference, Wu backstory, even his own discography stretching out before and after this point can’t obscure the shock of breathless emceeing here. Nor can the dazzle of its competition to reach this place, nor can the reams of singles that have truly defined this genre this decade. “Stay Fly” can’t beat this. “B.O.B.” can’t beat this. Hova man-king can’t beat this, Can Ox can’t beat this. It is the triumph of one person—of one mic. In that capacity it fulfills hip-hop’s promise as a forum for artistic excellence among the systemically forgotten. With Illmatic, it is the most remarkable album-length performance by an emcee ever recorded.

Clayton Purdom

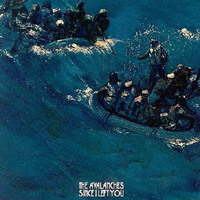

1 :: Avalanches

Since I Left You

(Modular; 2000)

SILY slyly asks, “can you think of anything else that talks, other than a person?”, and answers “a record,” as if it itself can talk. Silly, right? Or serious? Because SILY sort of asks this all-important question importantly by proxy, sort of. It’s vocalized second hand, but is not second hand in its vocalization; it’s just a sample of what you may already be thinking. It’s your voice, I mean; you’re asking—obviously, since we’ve all asked this—“why does this album talk to me?” While you ponder, Suzy also wonders who is looking at her; champagne gets poured; people get on planes; people party; the joint gets turned upside down, featuring a whole lot of flutes; tonight may have to last you your entire life. That’s the text—this is a party record; a hip-hop record; a breaks record—and the way this album gets talked about you would think listening to it would be like ingesting Ibiza. Ingesting the sun, even. Somebody probably wishes the word “balearic” had been invented in 2000. And maybe I’ll get 2000 emails for that factual inaccuracy, one for every year of the 2000 years previous to the one when this thing dropped. Those very sad 2000 years, I mean.

Because Since I Left You isn’t a culmination, or an anticipation; this is a cusp, a wormhole. It’s everything second hand, lit up in first person, sped up to the point where everything is blurred, since it never left us with anything but things we love. In 2000, it was a manifesto (intentionally or unintentionally) for a decade that hadn’t happened yet: a world so new. This is promise in its purest form. “Can’t you hear it?” But it’s also a funnel, where the second hands cup together to funnel us from the 1990s to the 2000s. I just got to that part in “Electricity” where future M83 gives way to past The Chronic (1992) and then they play in tandem, like they’re in love. “Some birds are funny when they talk.” Do you think Dan Snaith listened to “Extra Kings” before making Up in Flames (2003)? Isn’t “Radio” just better than most of the DFA catalogue anyway? Isn’t “A Different Feeling” blueprinted off the rhythms of a tiger’s orgasm? Is it that epic, or is it just a band having fun? Does it matter? There’s enough mythology; I like this album way better than Endtroducing (1996); I’m not the one to talk about how sick the process of collage is here. I mean, I actually probably am, but I won’t. Neither will I quote Bismarck about sausages. I’ll just hint at the quote, since this album doesn’t succeed by being literal anyway, Girl Talk. Since I Left You blurs; you’re just blurry. You’re just “an ophthalmologist” with “juice on your chin.” They’re the “Frontier Psychiatrist.” A real frontier; a place where everything is possible. Even sampling what I’m pretty sure is an Anthony Banks synthesized string riff from We Can’t Dance (1991). The frontier is always a collage, where the new and the second hand meet.

Also second hand, in the sense that means “abandoned” or “left behind”—“pre-loved”—was an erroneous piece of mail that arrived at my Toronto home last week. It was for nobody who lives here; it was for everybody, therefore. Just like this album. There are three apartments and a restaurant here; none of us listen to the same music, but thanks to albums like this we all kind of do, whether because when I blare this in our kitchen and I wander to another room for a moment I can hear “Flight Tonight” thrumming through the walls like a bumping party downstairs or because this album is every music anyway. I was making carrot cake when I realized that. I put bourbon in my cream cheese icing to make it less cheesy; the Avalanches somehow strike the same balance and avoid a slight half-step left to cheese-stache purgatory. They left the right way, I mean: this is an album that samples Madonna and that band with that song with that chorus with that line, “Oh Annie / I’m not you’re Daddy / But if I were you wouldn’t be so ugly.” And with that, I dedicate this blurb to Annie, because as groovy as they were, Kid Creole and the Coconut Gang were kind of douchey. Kid Creole should be the recipient of this week’s bonus Band Name Anagram: a “canal shave.”

Scratch that. I’m going to dedicate this blurb to Leah—who I love despite the fact that we do and don’t love the same music; who I can live with because we both listen to every music anyway—who once demonstrated in the most poignant way exactly how the samples on this album work. Normally, Leah won’t eat unethically raised meat. She’s very strict about this, except when she’s drunk, and she suddenly really wants Chicken McNuggets. She even has a little song that she sings to me about sweet and sour dipping sauce. But sometimes you just want Chicken McNuggets, right? No matter how suspect their production/cred/creation was or is. Sometimes you just want sweet and sour. This record is both, thankfully. And with 3500 samples, that’s like 3500 bursts of either. Some are sharp and some blunt, but they turn the joint upside down. They leave juice on your chin. Sweet and exotic, but not foreign. This album doesn’t play that game. Maybe a kumquat? Can’t you hear it? Check that really slow part on “Etoh” that sounds like the beginning of an awesome Animal Collective song 4 years early, before somehow the band manages to distinctly capture an impression of dancehall and afro-beat playing simultaneously, before “Summer Crane” yé-yés its arrival on a breath of Steve Reich vocalization, before that Genesis quote. And that’s without mentioning that “Summer Crane” sounds like Gang Gang Dance. That’s two songs. This album, in the most literal way possible, links all of our spines together to form a staircase that reaches the heavens. It’s a bunch of dominoes that fall into one another. It blurs the lines between creating and collage; it acknowledges what our entire lives are anyway: a collage of ideas folded into one another.

And so I folded the wrongly-addressed letter into a summer crane. It was addressed to a person named Vance Ernst. Possibly he’s Annie’s brother, or son, or daughter; across generations we tell stories that draw us all together anyway. Maybe he’s the daddy; maybe he thinks he’s a Daddy O; maybe he’s the guy who created Chicken McNuggets. Themselves a collage, really. The letter was from a gym; the address was an apartment that doesn’t exist in this building; the name sounds fake anyway. “Vance Ernst.” I mean, come on: Vance Ernst is a joke. Vance is also a collage; he is all of us. Vance Ernst dreams of going to the gym so that when music like this plays his body is always ready: taut, sharp, and thick. It is music that demands you be ready. Booming. In this, Vance is better prepared than me. I can only offer carrot cake and a beard full of past carrot cakes. And the internet, since even with all the every music I listen to, I don’t always know what’s happening on this album. Like, so many flutes and not one Bobbie Humphrey sample? Who picked this for our album of the year? Is that the question you’re asking? I couldn’t hear; I’m at that part in “Pablo’s Cruise” that sounds like a Philip Jeck joint. Does “Spockily” mean “as Spock would do it?” Because with everything I’m saying, there’s also just how fucking good this shit is.

The secret—and maybe Vance knows it—is that the stray bits are vaguely familiar but never recognizable. Consider: was this blurb hard to read? Did it make you hungry for carrot cake? That’s kind of the language version of what the Avalanches do. Stray bits and pieces and ideas reformed as unfurled sails that propel shit forward. Cosmic shit, I mean, wrapped in nautical imagery. Hell, even the artwork is specific, but then cropped to become unspecific, new, and meaningful. A painting of a ship sinking becomes a painting of different boats with just one fluctuating wave caught between them. Point being, Since I Left You isn’t silly or second-hand at all. It is unrepentantly immediate. Its ground always shifts; it is a frontier. An album from 2000 can be The Album Of The 2000s because it is the future built of the past. I mean, repetition is what repenting is, right? Since I Left You is like a millennial rosary chain, a history textbook with no course to assess you, ideas refashioned to a collage that is blurred enough that it loses any sense of collageness. Which is why even though I’m sure Vance and I have nothing in common, this album is both of our albums of the decade because this album makes me and Vance the same: defined as undefinable, a unique whole built from repetitive parts, and pretty awesome besides. Come on: nothing talks like Since I Left You, and it talks to you because it talks like everything.