Features | Interviews

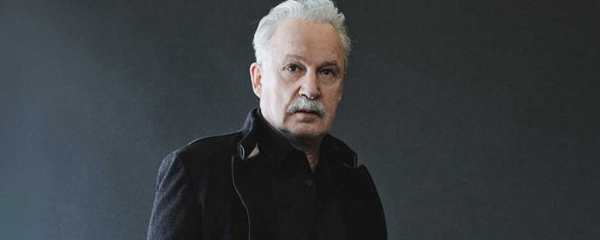

Giorgio Moroder

By Jordan Cronk | 18 March 2014

After a year which has seen not only belated recognition for one of music’s most influential artists, but also new collaborations, unexpected triumphs as a festival performer, and subliminal ubiquity from Super Bowl commercials to below-the-line Grammy honors, it’s safe to say that Giorgio Moroder is no longer having a moment, but a full-on renaissance. After appearing on Daft Punk’s world-conquering Random Access Memories (2013), Moroder has embarked upon an unforeseen new chapter in his professional life, bringing a new generation of fans into the fold while solidifying his status as one of pop and electronic music’s most versatile producers. Moroder was kind enough to sit down with me at his home in Los Angeles to discuss his recent resurgence, the extent of his influence, the simultaneous ease and difficulty of new recording technologies, the ethics of sampling, and why a third act turn as a DJ may have been more inevitable than people realize.

CMG: The last year or so has been an eventful one for you, to say the least: collaborations, live performances, remixes, new songs, etc. Was there a moment when you realized you weren’t just back in the public consciousness but were now exposed to an entire new generation of kids, all potentially discovering you at once as a result of these various new pursuits?

Giorgio Moroder (GM): Well, the discovery with the younger people was not only that the album with Daft Punk, and especially my song “Giorgio By Moroder,” was doing so well, but also since I’ve been DJing I’ve noticed that young people know my songs. I was in Mexico, for example, or Germany, and the audience was all—well not all, but the oldest was slightly over 40—so all 18 to 40 years old, all young guys, young people knowing my songs which I composed what, like, 30 years ago? So that’s when I thought, “I’m back,” not only in the press and all that, but back with the young kids.

CMG: Well, it’s funny because you can hear your influence in say, Daft Punk, of course—who have been influenced by you for a while but only now literalized the influence and made a song with you and named it after you as well—but also in artists like Todd Terje, some of the Italians Do It Better bands, even Hot Chip. Prior to a year ago, then, where do you think your influence lie for younger musicians, and did you feel like this exposure would come back around anyway, as trends tend to do?

GM: I’ve been reading for the last ten years that a lot of EDM music, dance music, borrowed or was inspired by some of my songs, especially [Donna Summer’s] “I Feel Love,” which was the first all computer-synthesized and generated music, so in the last ten years I’ve read almost on a daily basis how people were inspired—like, that song by that group reminds them of “I Feel Love.” But it became much more obvious with the release of the Daft Punk album. Actually, I’ve been reading about stuff like that for probably 15 years.

CMG: Before we get into some of your newer work and collaborations as a result of the Daft Punk album, let’s go back a little bit. How did you first get exposed to music? Did you grow up in a musical family?

GM: No, no, I played guitar and a little bit of bass and a got an offer to play in a little group, so I left school at 19 and became a musician. And slowly, because of this—well, not because, but I eventually decided not to be a musician and became a composer, and I was quite lucky because I had my first hit probably about six months after I decided to leave and become a musician.

CMG: I know you gathered some early material on a compilation recently (Repertoire Records’ Schlagermoroder Vol.1: 1966-1975), and I’m very interested to talk about your earlier music, before you kind of broke out, as it were. Particularly your record Einzelgänger, from 1975, which seems more interested in or influenced by German music and krautrock of the time, at least compared to when you would embrace full-on disco soon after. The record has a German title and there are references to Germany in some of the sing titles like “Good Old Germany.” Was that style of music an influence?

GM: I don’t even know if Kraftwerk, who would do something similar, were even much around. That was a time when I did a lot of work with synthesizers, though my first work with the synthesizer was the song “Son of My Father,” which was in ‘71. And that was way before Kraftwerk—or at least before their first hit, “Autobahn,” which was ‘74. The song “Son of My Father” actually had the first use of a synthesizer in a pop song. There was a [rock] song that came out a few months earlier by Emerson, Lake and Palmer called “Lucky Man” [that also utilized a synthesizer]. But my work with the synthesizer actually started at the same time, in ‘71.

CMG: Well, obviously Einzelgänger was darker than what you’d end up doing. Even Giorgio’s Music, from around the same time, is brighter and happier, almost like ‘60s psychedelic music at times.

GM: Well, before “Son of My Father” I did all kinds of junk, like “Looky Looky,” which was a happy song, a little bubblegum. I loved, and still like, the recording now—it was well done actually, and it became my first international hit.

CMG: Then why the switch to full-on electronic music in mid-‘70s? Was that just a natural progression?

GM: Well, I discovered the synthesizer, the first Moog in Germany and I think the third Moog on the market. So having a new instrument, and an incredible new instrument, I thought, “This is my instrument. I have to use it as much as I can.”

CMG: So then you focus on producing for a number of years, begin working on scoring films in the ‘80s, win a couple of Oscars in the process, before settling down professionally. Then you start to hear about your influence on younger artists, and fast forward to today and Daft Punk just…contacts you? Did you know at the time what the collaboration would be, the extent of it, as an actual homage to you?

GM: We had lunch one day here in Los Angeles and we were just talking in general and one of the two guys asked if I was interested in working on some tracks, and that they were working on a new album. And I said, “Yeah, yeah, whenever you have an idea, let’s talk.” So one day Thomas [Banghatler] called me, and I was in Paris at the time, and he asked if I could come in the studio and just talk about my life, and that’s all.

CMG: And that’s where your speech from the track comes from?

GM: That’s right. I spoke for two hours and at the time I didn’t know what they wanted to do. I thought maybe they wanted it to use as a little cut-up of some words into a hip-hop style song. But they didn’t tell me. And then the first time I heard it was about a year ago, in February I think.

CMG: It’s funny you say that about cutting-up your voice because I feel like prior to this comeback, most of your audible influence was in the hip-hop realm. I mean, artists have been sampling your stuff forever it seems, in a way that many listeners may not even realize. There was J Dilla, Cannibal Ox, DJ Shadow, Outkast—all sorts of stuff. How do you feel about sampling and techniques like that? You did stuff like that early on, right?

GM: No, I don’t think I did any actual sampling.

CMG: How was Knights in White Satin made?

GM: Oh, that was all new—a remake of a song. But I don’t think I’ve done any sampling in my life. Not that I remember at least. And to be honest I wasn’t really paying attention to who was sampling my stuff. First of all, if they would do it and they would actually pay, they would pay the record company anyways, so I wouldn’t know. And sometimes the samples are so well done that you don’t even know. Sometimes I listen to songs—yesterday, in fact, I was listening to a song, which is a big hit, and I heard that it sampled—or had taken, really—a song by Pharrell. And it took me quite some time to figure out what they were talking about, because if you take a sample and change it enough you can’t even recognize it. There’s one piece of a Kanye West song called “Mercy” where he samples part of the chords from Scarface, but he cut them up in a way that it’s difficult to say, “Is it or not?” So if they take it and pay for it, that’s great. If they just take it and change it, that’s not so great.

CMG: And you’ve been remixing a lot of new artists recently: Haim, Claire, you own music even—you remixed some of the Scarface music and some of the old Donna Summer tracks. A lot of this material has gone up on your Soundcloud—you have a few Soundcloud accounts, actually. How do you feel about this new technology, getting your music out in that way?

GM: Well first, I like that the songs are available on Soundcloud. But some of the songs I didn’t put up. I don’t even know who did. Because you can open up an account and put up whatever you want. And I would only put music up with the permission of the record company—except of course the remixes, which I own.

CMG: So you like how readily available your music is now? Or if you wanted to release something on your own, like a remix, you can?

GM: Well with Soundcloud you can’t really [make a] copy of the song. You can just listen to it, which is great. So people can hear it. I mean, it’s all promotion. But to release a song through the label it’s all, “What are you going to do, what can you do, what should you do, what you shouldn’t you do?”

CMG: The one thing that probably surprised me the most in the last year is that you’ve started DJing. But what surprised me the most about it wasn’t the fact that you were DJing, but that apparently you hadn’t done so prior?

GM: Zero.

CMG: Was that a conscious or purposeful decision? Or was it maybe a technology thing?

GM: Well, it started by coincidence. I did a thing—it wasn’t really DJing, but I did a thing for a Louis Vuitton Paris [fashion] walk. And then the Red Bull Music Academy asked if I could be a member of the teachers who spoke to their students. And I thought it would be more interesting if we could combine it with something, because I didn’t really want to travel all the way from Paris to New York just to talk [on a panel]. So they said yes, we could start a DJ evening [to coincide]. And that was my first DJ [show].

CMG: And you’ve been doing it multiple times since.

GM: Yeah, it’s great. It’s a lot of money, but most of all it’s fun. In Mexico, I performed in front of 20,000 people. It’s quite interesting to perform in front of that size audience.

CMG: What are the sets comprised of, only your music or other stuff as well?

GM: All my music. I have one piece which I like, which I re-edited and put some new stuff into, but it’s basically all my music.

CMG: And you’re starting to record some new studio material now. Can you talk a little bit about how recording has changed for you, technology-wise? Is the process different now?

GM: Well, the process is different now. But I can’t name any names [or projects] because nothing is set. But the tendency now is that the composer composes the tracks with a melody but then most of the time the artists or the producer comes in and invents new melodies, so it’s kind of rare now that you can present a song with the tracks and all the music and melodies and the lyrics, because everybody wants to be involved, and the singers that are coming up are quite good at coming up with great lines, great hooks.

CMG: What about the equipment you’re using now?

GM: Lately I’ve been using live drums, guitar, and bass—and sometimes Fender Rhodes and clarinet. The other stuff, violins and all that stuff, it’s in the computer. So I use digital sounds. You know, we have [access to] millions of sounds.

CMG: Do you even think about it being different than how you used to record, or is it just a natural byproduct of working with current technology?

GM: Well, I’m not saying it’s easier. It actually takes much more time the way it’s recorded now. Because in the disco times I had five musicians and it took me about two hours to do basic tracks and an hour to do the strings—you know the strings you can’t change too much. Now you have 200 strings and it takes time to find the right ones. So the process is much more complex, and I’m not saying difficult, but just much more time [consuming] than before.

CMG: A lot of your most popular work has been done in collaboration with other artists, and recently you’ve been doing a lot collaborating as well. You did a Super Bowl commercial just recently.

GM: Yeah, that was an old song.

CMG: Was it remixed?

GM: No, just re-recorded—but in the style of the original.

CMG: Yeah, what did you call it, “Doo-Bee-Doo-Bee-Doo 2014”?

GM: Yeah, [the original] was…‘69, right? Over 40 years ago.

CMG: And that track for Google Chrome?

GM: That’s a new song.

CMG: What about the Las Vegas show in the style of the Studio 54 days?

GM: That’s still in air. It’s not confirmed. We’re talking to two hotels, but that’s quite a big project and we’re still talking and nothing’s confirmed.

CMG: So right now it’s mostly live shows? You played the Station to Station tour and you have Pitchfork Fest coming up in July.

GM: Yeah, I have about eight gigs coming up. On May 10th I’m here at the Hollywood Bowl.

CMG: So in closing, would you say that you were content before simply knowing you had this influence over a lot of popular music and satisfied with where you were professionally, before getting all this belated recognition from a new generation of listeners? Does it feel sort of like happenstance and you’re just along for the ride, or were you interested in pursuing a comeback anyway?

GM: No, no, I was happy playing golf and being retired. But I always did other things, like computer generated design.

CMG: So you considered yourself essentially retired?

GM: Yeah, I wasn’t worrying too much about music.

CMG: Yeah, because I feel like trends do eventually come back around, and like you mentioned before electronic music has become much more popular in the last few years, at least in a mainstream sense. But music writers and really well-versed music fans have been well aware of your influence for a while now. But it really took that guest spot with Daft Punk to bridge the gap for more casual music fans. And it’s obviously opened up a lot of opportunities for you.

GM: Yeah, I’m not sure if I didn’t have the song with Daft Punk [if I would be back to such an extent], but I probably would have done the same thing with DJing. Because the DJing thing actually started two years ago with Louis Vuitton—I hadn’t even spoke with Daft Punk. And then by coincidence a year later I heard from Red Bull in New York. So I probably would have done DJing without the Daft Punk thing. In fact, I got some offers before the album even came out. I had the one from [Red Bull in] New York and then I went twice to Tokyo, and the Tokyo thing was booked more than a year ago. So there’s chance I would have become a DJ anyway.