Features | Lists

By The Staff

30 :: Bill Callahan

Sometimes I Wish We Were an Eagle

(Drag City)

It’s hard not to write about Sometimes I Wish We Were an Eagle without beginning by addressing “Jim Cain,” where Bill Callahan provides a single line that’s simply too apt a summary not to include, as almost every reviewer did: “I used to be darker, then I got lighter, then I got dark again.” It’s also hard not to write about this as a breakup record, which makes it hard not to write about Callahan’s personal life, recently defined by a breakup made public despite the fact that none of the parties involved, to my knowledge, have said anything to any press outlet about it.

And these are almost undoubtedly breakup songs. Callahan struggles with memory and can only yield nonsense in “Eid Ma Clack Shaw,” can’t process his lack of agency on “Rococo Zephyr,” and sees birds across all of the album’s darkest moments (“The Wind and the Dove,” “Too Many Birds,” “All Thoughts Are Prey to Some Beast”). A lot of the relative lightness, or even dark humor, scattered throughout Callahan’s back catalog is absent here, and this could be his most intense album since 1996’s The Doctor Came At Dawn, though it’s much more approachable. Unlike Neil Hagerty’s on its predecessor’s, Brian Beattie’s arrangements render these songs considerably more welcoming, strings and horns enriching Callahan’s songs as much as his own memory haunts them.

About a year ago someone I haven’t seen since told me that he thought A River Ain’t Too Much To Love was Callahan’s best record. His case was straightforward: on A River, Callahan had mastered the use of repetition, both musically and lyrically, as songwriting tools, as he is able to say so much by repeating so little. On Sometimes’ best song, “Too Many Birds,” he spends a great deal of the song adding one word to a repeated line, shifting its meaning almost completely each time, to astounding effect. John Darnielle, another exceptionally gifted songwriter, asked for his readers to “just pause for a moment to consider the ongoing magnitude of Bill Callahan’s accomplishment.” Few records can get away with being so personal in their scope while still saying so much, and few songwriters age so well, as Callahan’s second under his given name will likely prove as strong as those from his astounding run a decade earlier.

Andrew Hall

29 :: Blackout Beach

Skin of Evil

(Soft Abuse)

The fingerprints of Carey Mercer’s dark genius are all over everything he touches—one need only see Frog Eyes or Swan Lake for the depth of his nuanced and distinct songwriting voice—but his Blackout Beach project is miraculous in its own way. Not only because, even after the gargantuan complexity of Frog Eyes’s Tears of the Valedictorian (2007), material is still (somehow, maddeningly) flowing out of him, but also because it’s the most direct manifestation of a truly idiosyncratic aesthete at work. Here all extrapersonal accompaniment is treated as so much unneeded adornment and Mercer opts instead to chorus with his split selves, to display crystalline identities ugly and essential. It’s his hardest, most poetic statement of self-exploration yet. Skin of Evil sounds like just that, pulled over Mercer like a Snuggie made of patchwork human skin. “Cloud of Evil” is a simulated duet of pure malevolence that gathers melodic tendrils around the edges of a personality; Mercer seems to argue against the world with himself, chorusing with a threatening beauty, and it’s the most bracing opening song of the year. Anxious, complicated, troublesome, an ethereally gorgeous fever dream, Skin of Evil may someday prove to be Mercer’s most honest—if least accommodating—and thus most essential work.

Conrad Amenta

28 :: Humcrush

Rest at World's End

(Rune Grammofon)

Rune Grammofon could fold tomorrow and they would still carry a legacy in avant-garde and experimental music that would rival any other label of the last two decades. That having said, a lot of their releases over the last couple of years, while varying in quality, have had the undeniable feel of one-off sessions. Not that there haven’t been a slew of unedited improvs that are just as valuable and replayable as laboured-over studio albums, but only when they somehow manage to transcend their humble origins.

On Rest at World’s End, the tension between spontaneity and forethought is so palpable it hurts the brain to try and conceive of the logistics of how it was made by only two people. The album adds a great deal of atmosphere to the more techno-funk oriented Hornswoggle and yet it remains endlessly rhythmic. Whereas Ståle Storløkken’s parent band Supersilent tends to rise together as one unit, Humcrush thrive on interplay: some tracks are soft and sparse, some furious and skronky, some even a bit of both, but the importance always seems to lie in how Storløkken and Strønen are interacting. It’s almost as if the duo are taking the abject virtuosity of fusion-era icons like Herbie Hancock and Chick Corea and splintering it apart, inserting negative space in a way which is virtuosic itself, as if restraint were a technical skill that can be wielded at any time. Did I mention this was a live album? And on the seventh day after raining hellfire and brimstone and eviscerating the Earth, the Lord said “It is good” and took a much-needed nap.

Joel Elliott

27 :: Lil Wayne

No Ceilings Mixtape

(Self-released)

It took my downstairs neighbor, a kindly older man who I think works weird hours and who averts his eyes when we cross paths on our shared landing, eighteen months to complain about my repeated belligerence in regards to the volume knob, and in a delightfully apropos turn it was “Swag Surfing” that did it. Because on No Ceilings Lil Wayne debuted an almost molecular change to his flow, something less tied to the beat, less reliant on wheedling vocal ticks and half-sung punchlines, something less Gollum and more Treebeard. Shit sounds loud, painting with generous blank space so each word hits seismically. And while on this mixtape it’s fun to hear him apply this revivified focus across the radio dial—I swear to God, listened front to back, even that Black Eyed Peas track works—opener “Swag Surfing” is one of those spine-shivering Weezy Tracks like “I’m Me” or “We Takin’ Ova” that shimmers with electric inspiration, renewing the baptismal vows of the faithful and casting out a righteous spirit too infectiously loud for the unconverted to deny. Except, perhaps, my downstairs neighbor. But fuck him.

And anyway, thank fuck for it (the mixtape, not my neighbor), because I was getting sick of half-defending Lil Wayne’s rock songs and chemically disintegrating mic-work. Headphones reveal a surplus of weed at No Ceilings’s recording sessions (bonus game: find the verse on “D.O.A.” wherein he’s holding back an exhale) but overall his wordplay sounds disarmingly sober, his topicality rewardingly consistent from line to line. Which is something he had started to sound incapable of doing, really. And which is what we and he needed: a post-Carter 3 chart-able progression that didn’t seem toward an early grave or self-parody but followed that dramatic slope from Cash Money through Dedication 2 and The Leak, that inimitably single-minded slope of his that suggests a volatility for steepening sparking off each word and an interest in proving geometry wrong about just how high that y-axis goes. With ambition like this Wayne’s got neighbors nation-wide putting on bathrobes.

Clayton Purdom

26 :: Harlem Shakes

Technicolor Health

(Gigantic)

Technicolor Health is one of the strongest straight-up indie rock albums in recent memory, borrowing the most satisfying conventions from every one of the genre’s major players and executing each little gesture deftly, lined with great hooks and, yes, quick quips; landing when this did it feels like both a compendium of and reflection upon the movements that made up Indie Rock across the 2000s. It’s not just a great indie rock record, it’s the Last Great Indie Rock Record. Ten years from now we’ll point to this and say, yep, that pretty much sums it up.

But you slept on it. I’m not talking about The Critics, who either totally ignored this (ignorant) or else totally slammed it (incorrect). I’m not talking about The Industry Representatives, who, quite inconceivably, heard “Strictly Game” and decided that it would not be the perfect soundtrack to any number of rom-com trailers or cell phone commercials or Gossip Girl finales. I’m not even talking about us, who regrettably handed this album a rating several points too low to make anybody pay it the attention we now understand it deserves. No, I’m talking about you—you, reading this right now. You slept on this record, and seriously: not cool. The Harlem Shakes broke up just a few short months after Technicolor Health dropped, and we know this to be a terrible loss. If you’d listened to this album, if you, specifically, had gone out and purchased this thing, if you’d stormed their shows and screamed their name, if you’d relished the fact that a straight-up indie rock band can still manage to produce a straight-up indie rock record that is so thoroughly satisfying and just good, and if you had insisted that the band stay together, maybe they would have, and maybe they’d continue to release pitch-perfect indie rock records, and maybe they’d catch a break and finally find the critical and commercial success we know they really deserve, and maybe, just maybe, we’d still have a truly great indie rock band in 2010. Go back and see what you missed—you’ll lament their loss soon.

Calum Marsh

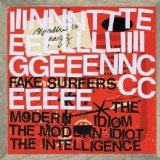

25 :: Intelligence

Fake Surfers

(In the Red)

If the God of Rock were to ask me, “What is the best rock record of 2009?”, I might well look at him thoughtfully before replying Wolfgang Amadeus Phoenix. The God of Rock would then debag me and drag my remains to a burning pile of Phoenix CDs before explaining, in massive stony chunks of text, that Phoenix is not a rock band—not a rock band. Then I would die.

Somewhere about now I need to make a point about Intelligence. Fact is, if the God of Rock really existed, I’d be pulling him by his horned head in the direction of Fake Surfers. The fourth record by the band is a front-to-back blast—no hiccups, no fart noises, and absolutely no fucking around. This is an album royally razed out of a decaying scene, and the Intelligence, you can tell, give not a shit about popular fads. The sound effects are pure wacko; the use of whistling: debonair. They got this one just right. The songs themselves are tight little things, but the performances don’t hold to their meaning or obvious pleasures. Hooks are batted about and often dropped altogether in favour of making (lighthearted) fun of other bands (“Fuck Eat Skull”); melodies are appropriated and then lovingly skewed; and what passes for a bit of self-referential razzmatazz (“Thank You God For Fixing the Tape”) suddenly turns into this year’s biggest, horniest teenage anthem. I love it all.

The ghosts of tens of other bands haunt these songs, and in turn these songs pass for mini-exorcisms. Lars Finberg, fronting the big melee, is performing the ultimate tongue-in-cheek. (“Moody Tower” even begins with a muffled pock.) What is most impressive and most endearing, though, is the uninterrupted sense of creators at play. Nothing on Fake Surfers feels too worked on, but none of it is shoddily put together either. The songs are capricious and absurd, and the band approaches them like a bunch of drunk robots. Bravo.

Alan Baban

24 :: Do Make Say Think

Other Truths

(Constellation)

The first two tracks on Other Truths are twenty-three of the best minutes of post-rock since Explosions in the Sky’s heyday, demanding they be turned up loud or listened to on headphones. And it’s the moments that make it work: a minute and a half into “Do” when the bass hits and the thing suddenly gels; the rolling drum line into “Make,” where the bass again appears and locks everything together; the horn/distortion combo about eight minutes into “Make.” The guitars have stellar tone and interplay throughout, the drumming is fabulous, and the horn section works wonders at various points. But even if Other Truths is a bit front-heavy, the back half is still good—even in an off-year like ’09, half an album wouldn’t cut it. The exceedingly pretty, sweeping “Say” may come close to matching “Do” in overall effect, even if in the moment it’s not quite as affecting. This is the sound of a band rejuvenated with a sense of purpose.

Peter Hepburn

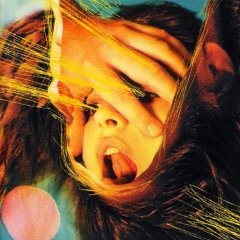

23 :: Flaming Lips

Embryonic

(Warner Bros.)

The Flaming Lips have often sounded huge, but on earlier records this was the product of energy expelled infinitely outward toward something empty but open—they were bright, expansive, a sky upon which Wayne Coyne could forge fantasies from clouds. Embryonic retains the enormity, but now that space feels contained, its limits sharply defined, so that the whole begins to take on a coherent shape. Coyne dreams just as big, but his ideas now hit walls—they meet resistance, they reflect and reverberate, and in the end they sound sprawling but newly confused.

And so the Flaming Lips have released a two-disc, seventy-minute album that sounds positively cavernous. Few could have anticipated such boldness at this stage in the band’s career, and for those who had long-since given up on Coyne by the time “The Yeah Yeah Yeah Song” began sullying every rom-com soundtrack it could worm its way on to, the temerity of the gesture was itself reason enough to get excited. The very idea of Embryonic is satisfying. But what even fewer could have anticipated is that Coyne’s audacity paid off: Embryonic is less an interesting and surprising experiment than it is just a great album. And for the Flaming Lips, who in the ten years since their last great album have managed to alienate more long-time fans than the average indie mainstay sees at the zenith of its career, Embryonic’s success couldn’t have been more fortuitously timed: as though he knew we could brook his idiosyncratic fairytale bullshit not a moment longer, Coyne swooped down from some mystical headspace to render these ideas more precisely and beautifully than we currently conceived him capable. This isn’t simply rejuvenation, it’s credibility-resuscitating vindication.

Calum Marsh

22 :: Sunn O)))

Monoliths & Dimensions

(Southern Lord)

Sunn O))) continue to operate within the self-imposed confines of such a narrow aesthetic niche that one generally understands the sorts of pleasures a new Sunn O))) record will likely provide. And so had Monoliths & Dimensions simply reiterated Black One—had it been just another foray into visceral, death-affirming drone—that would have been entirely acceptable. Because what’s so satisfying about Sunn 0))) is not that their ideas about what drone should or could mean are wildly experimental or challenging or even new, but that they understand better than the heavyweight practitioners of just about any other niche genre that making great drone music precludes making music drastically unlike drone. And so, in repeating themselves, Sunn O))) continue to be the best drone band running.

But on Monoliths & Dimensions, Sunn O))) have, without coloring too far outside the lines, crafted a progressive, forward-thinking drone album that simultaneously redefines and, most importantly, reconfirms our ideas about Sunn O))). Yes, the instrumentation is more full-bodied that ever before, but the presence of a french horn and a harp do not, as the band has made explicitly clear, imply that this is just “Sunn O))) with strings”; richer instrumentation does, however, make Monoliths a much denser and much more abstract whole than its predecessor. These are abstractions of feelings, vaguely defined: feelings of anxiety, of fear, of impending death—as Joel observed in his review, it’s not really about death but about your death, specifically. Plaintive stuff, but the sorrow’s laced with a kind of transcendent hope: listen again to the last few minutes of closer “Alice,” where death becomes an act of beautiful resignation. Nice sentiment? Perhaps, but then think again: we’re all on our way to that end ourselves. Sunn O))) are just here to remind us of what’s waiting.

Calum Marsh

21 :: St. Vincent

Actor

(4AD)

Though it certainly had its moments, Annie Clark’s 2007 debut under the name St. Vincent often felt too composed, too comfortable in its own prettiness. But if Marry Me was the stylized photograph, then Actor is the negative: a record crafted from familiar elements turned eerily inside out. Smiles become sinister, the whites of eyes go black, and the poise that characterized Clark’s vocal delivery on the debut transforms into something truly disquieting. “Paint the black hole blacker,” goes Clark’s sing-songy refrain on opener “The Strangers.” From the get-go, the darkness that permeates Actor is evident, both thematically and musically; that track, like many others here, begins with a deceptive sweetness and ends in sonic corrosion, swirling like a carousel on fire.

Clark harnesses an abrasive electricity throughout, especially on stand-out track “Marrow” where Clark sings, “H-E-L-P / Help / Me / Help Me” with a haunting detachment—the one moment when Actor allows itself to linger in its own blaze. The album eventually tries to put itself back together during subsequent (and disappointingly prettier) songs, before culminating in the lovely and climactic “Just The Same But Brand New.” The track twinkles with dreamy arpeggios and then ascends to a soaring, cathartic conclusion. The titular assertion “I’m just the same but brand new to you” is actually the opposite of the truth: Actor has given us a glimpse of the crackling anxiety underneath Clark’s veneer and her deceptively glassy countenance will never appear quite the same again.