Features | Lists

By The Staff

20 :: Baroness

Blue Record

(Relapse)

Consider the range of solid-to-great metal albums this year, from Sunn O))) to Wolves in the Throne Room to Mastodon to Baroness: these guys are covering a lot of ground. Baroness click for me, though, and I agree with Chris Alexander’s assessment of why: they are cribbing from some of the best of classic metal, but they also make sense to someone who grew up on Fugazi and At the Drive-In.

Truth is, there’s not much to not get about Blue Record. The album is monstrous and unstoppable. It’s 44 minutes long and feels ten minutes too short; there’s not a dull moment on here, not a song that feels stale or warmed over. Baroness keep things concise, but every time a track seems to be locking into a set groove, they’ll push something to another level—listen to the rhythm section particularly—to pull you back in. Guitarists/singers John Baizley and Peter Adams are both furious and playing furiously the whole time, while Alan Bickle throws down some of 2009’s most understated and ridiculous drum work. I’ve been listening to this over and over for months and I’m still finding things that blow me away.

Peter Hepburn

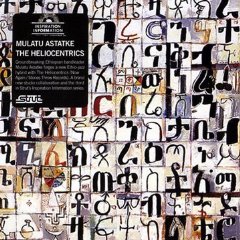

19 :: Mulatu Astatke & the Heliocentrics

Inspiration Information 3

(Strut)

Um, this is the record Blockhead always wanted to make? My touchstones for this lush document are limited, but, like a transplant from the 19th Century watching Star Wars on Blu-ray, I feel, at my core, that this is revelatory. One doesn’t listen to Inspiration Information 3; one enters into a relationship with it, its nuances as seemingly infinite as those of someone you love. Trace the bold, horn-driven curves of “Dewel” to reveal some pulsing woodwinds, or find that the bleeding piano in the background of “Blue Nile” feels like gentle fingers up your spine: this is music borne from communion. As a fervent hip-hop fan, I’m used to sound collage—the re-contextualization of sounds to create a new whole—but, while this plays to my beat-fiend sensibilities, it’s a different entity entirely. Some passages knock in a traditional sense, but more often than not the compositions seem fascinated with exploration, the principal instruments wandering to miraculously stumble upon new, exciting sounds. The horn and guitar grooves are great, but what’s more interesting is the listening to how a dominant oboe or bass part is greeted and subsequently consumed by another instrument that once seemed to be a friend.

I know I’m explicating the appeal of jazz—the conversation of instruments and all—but this collection mines that appeal so capably and is so infectiously imaginative that it can construct a perspective of the world at once foreign and familiar as a childhood blanket. It’s odd that this collection draws its inspiration from western Africa, which despite our Internet-age shrinking of the globe still falls under the heading of “faraway land” to many of us, because it seems to have no origin or endpoint at all; Astatke and the Heliocentrics have created an active beauty of a record that manifests itself in the cosmos, brain cells, and anywhere else at all.

Colin McGowan

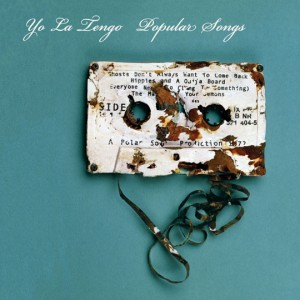

18 :: Yo La Tengo

Popular Songs

(Matador)

Recently I walked down the aisle to “Our Way to Fall,” the second song from And Then Nothing Turned Itself Inside Out (2000). My wife and I are fans. I suppose there’s also some, I hope, luck in that: Ira Kaplan and Georgia Hubley have somehow managed to maintain their marriage for twenty-two years. And every Yo La Tengo record since Painful (1993) has sounded like what I’ve envisioned a successful marriage to be, which is lived in and instantly familiar but always managing to introduce, now and then, something fresh.

Popular Songs is happily no different. The Hoboken-based trio of Kaplan, Hubley, and bassist James McNew still use the Velvet Underground as a jumping off point from which to explore every genre imaginable. And having Roger Moutenot behind the boards for his seventh consecutive Yo La Tengo album assures that the proceedings will be coated in that characteristically warm haze. Even a fuzz pop rave up like “Nothing to Hide” is to be expected. But this time out there’s a pointed emphasis on Stax-inspired soul: liquid Fender Rhodes licks and string arrangements on “Here to Fall” could pass for classic Isaac Hayes were it not for Ira Kaplan’s laconic vocal; the organ funk of “Periodically Double or Triple” cooks like a tamale-hot Booker T. Jam.

This being Yo La Tengo, there’s still room for a song that bears a passing resemblance to Fleetwood Mac’s “Gypsy” (“All Your Secrets”) and there is the purposeful jacking of the bass line from “Can’t Help My Self (Sugarpie Honey Bunch)” in the name of a charming husband/wife duet (“If It’s True”). And this still being a Yo La Tengo record, everything is somehow in its right place and loaded with hooks. It’s easy to take these guys for granted, but twenty-three years after their inception, Yo La Tengo remains totally in love with Yo La Tengo.

David M. Goldstein

17 :: Wolves in the Throne Room

Black Cascade

(Southern Lord)

Welcome to the sonic reinvention of “shock and awe.” Wolves in the Throne Room’s latest opus of righteous black metal is not content for you simply to “listen” to it. Opening blast of negative matter “Wanderer Above the Sea of Fog” is only melting your face so that it can have easier access to your soul; once it’s there prepare for images of fire and darkness broken by tactile rays of light, grotesque cherubim-battling Balrogs, the damned staging a revolt, God only knows what else. Loggers devoured by their own chainsaws, likely. I pity this dude for the shit he’s about to walk into. The chord progressions that WITTR chew through are on an epic melancholy tip while blast beats make short work of embedding the tip’s glint in your consciousness, pinning you to your figurative seat so you don’t miss the part after the lengthy mid-song pause where a drum fill gets shoved in a gatling gun and shreds your surroundings to pieces—which is followed by a rapid snare pound on the downbeat that hammers everything back together because, hey, you still got the rest of the album to listen to and there’s a lot more time for destroying the mundane scenery of the everyday. And the rest is just as good at it.

Like Two Hunters (2007) there are a few gentle passages of glistening ephemera to provide contrast, but whether the physicality of this music caresses or incites, WITTR never do less or even more than entrance. The subjugation is total, the mind enraptured. It’s not easy leveling analysis at a monolith, especially one as rock hard as this; you could call it unfeeling or brutal but the indescribable pathos that drenches these chords would call your bluff. Still “human,” this music, but not something we’re prepared for because so rarely does black metal try to do what Black Cascade most definitively does. And that is, simply, to cascade around the listener rather than assault, albeit to cascade with the intensity of a maelstrom held at bay by a deep-rooted respect for life in all its forms. In his interview with CMG’s Clayton Purdom earlier this year WITTR’s Aaron Weaver talked about the best intention black metal can have is that of the shamanic journey, a bold step forward and descent for that poor dude standing above the sea of fog into a dark realm with the purpose not to dwell there or join forces with Satan or whatever—as some black metal bands are wont to do (or they just get lost)—but to come back to share something positive with the rest of the community. That’s what this Black Cascade is all about: the band is showing us the darkness that we can’t always see in our modern lives but they’re also showing us how they fight the darkness. And they fight not just with the monastic way they live but with the strong and intuitive music they make.

It’s through that music that, yeah, they kind of drag us into the shadowy valley with them. So it’s quite the boon when they grab our hands on closer “Crystal Ammunition” and begin to make an upward ascent. The air starts to smell a bit sweeter, the fog parts, and as drops of fresh rain chase away whatever foul things may lurk behind us, we see dawn breaking over the ridge up ahead. And the dawn rings like a bell.

Chet Betz

16 :: The xx

The xx

(Young Turks/Rough Trade)

A quartet until the recent departure of keyboard player Baria Qureshi, the xx are a London-based trio of twenty-year-olds that were basically the Goth Kids on South Park. The rare British act that lives up to, and perhaps even exceeds, the hype thrust upon them, the xx have seemingly come from out of nowhere to release, based on physical description alone, a self-titled debut album that has no business being as awesome as it is. Their palette consists merely of a drum machine, sparse plucking of both bass and guitar, and the back and forth duel between Romy Madley Croft’s icy voice and that of equally icy co-lead Oliver Sim, as quiet and stolid as a tired conversation between lovers before bed. They invest as much energy into silence and space as they do their melodies; no single song rocks so much as pulses along at a paranoid gait. Young Marble Giants immediately come to mind in terms of its minimalist approach, but as the album proceeds The xx has more in common with the sinister shades of Massive Attack’s Mezzanine (1997) or Interpol’s Turn On the Bright Lights (2002). (First single: “Crystalised.” Indeed.) Croft’s timbre and phrasing sometimes even resembles that of the Cocteau Twins’ Liz Fraser—these kids have impeccable taste considering their relative ages. “Infinity” is a massive-sounding update on Chris Isaak’s “Wicked Game” and mid-album cuts like “Islands” and “Heart Skipped a Beat” throb like pre-One Republic Timbo (not for nothing that the xx have covered Aaliyah’s “Hot Like Fire” at their gigs). Destined, it’s possible, to become an atmospheric late-night classic, it’s also not much of a surprise that the xx wouldn’t have it any other way.

David M. Goldstein

15 :: Circulatory System

Signal Morning

(Cloud)

Man, where is the love for Circulatory System these days? Robert Schneider’s Apples in Stereo had a solid victory lap in 2007 with the release of New Magnetic Wonder. When Jeff Mangum’s arm hair wafts slightly, the indie world goes all bonkers, and Kevin Barnes’ psychedelic glitter penis has a starring role every night in my dreams. And yet when Will Cullen Hart, one half of the main creative team behind the Olivia Tremor Control, follows the brilliant self-titled debut of his solo project Circulatory System with Signal Morning, the zeitgeist barely notices.

Signal Morning is everything Elephant 6 fans could have wanted from a follow-up. A logical extension of Circulatory System and Hart’s work in Olivia Tremor Control, Signal Morning continues to focus on the venn-diagram-overlap of pop and noise that is contemporary psychedelia. Hart forgoes any jam elements, instead grafting ever more filtered and smashed sounds onto his songs. Thirteen years after the release of Dawn at Cubist Castle, Hart’s experimental side is as frisky as ever.

Hart’s canvas has always been large, and on Signal Morning it’s gigantic. Songs range from the twenty-four second sketch “News From The Heavenly Loom” to multi-movement suites in miniature like “This Morning.” The analog instrumentation (strings, woodwinds, horns) of his previous work is less of an element here, yet the paranoid electronics that replace them serve only to bring Circulatory System’s sound further out of the bedroom. Snippets of conventional-type songs emerge from the concrete fog only to dissipate again the next moment, as Hart’s fickle muse never allows him to rest long on a single inspiration.

Hart’s sonic nomadism is matched by his curious, solitary mind. Signal Morning is an album suffused by lonely questions, as opening lines from “The Breathing Universe” and “(Drifts)” ask “Why not try being alone with the universe?” and “Why can’t we drift along / painlessly along?” “The Spinning Continuous” wonders, “Have we come ‘round / have we come round again?” Signal Morning is a record searching, or the record of a search, for something, and though we cannot pinpoint the object we can be witness to Hart’s restless longing. And if it is sad it is defiantly so, and we can take heart that we have a companion who will not submit to being lost.

David Ritter

14 :: Pains of Being Pure at Heart

Pains of Being Pure at Heart

(Slumberland)

The Pains of Being Pure at Heart being the happiest album of the year, opener “Contender” sets the tone with a few guitar throbs notable not for their distortion, but for a striking lack of dissonance (the hums are octaves apart) and for a sprinting, brief segue into the first of many sunny jangles. From there, tracks are formed with basic major chords in simple, repetitive series of progressions, not a minor melody in sight. Every time Kip Berman sings something sad or a backing element suggests harshness something genially makes amends: a high organ hit, a shiny guitar strum, or a buoyant set of backing vocals. The lyrics either brim with optimism (“Strange teenager, you’ll never know death at nineteen”) or make cheeky stabs at negativity that no one can take seriously: “You don’t need a friend when you’re in love with Christ and heroin.”

TPOBPAH is also one of the most conservative albums of the year, breaking little new ground, wearing its influences on its sleeve, and never really coming up with many surprises. Negative reactions have had their share of selfish overtones, as if those of us who weren’t old enough to listen to Darklands (1987) or Snowball (1989) when they were originally released should be disallowed from having any fun with fuzzy guitars and reedy vocals. The Field Mice was not the first band to sound like this and Pains will not be the last. But even after considering critics and all their whinges—“these guys are poseurs!”, “their name sucks!”, “…did I mention Sarah Records?”—I’ll always come back to that amazing guitar solo in “Everything With You,” where, after a perfectly formed and perfectly timed buildup, the band treats us to twenty seconds of the most delicious feedback-drenched shoegaze bubblegum imaginable. The drum dropout and bumblebee buzz at the guitar entry haven’t gotten old after a hundred plays and won’t get old for a hundred more. Should they have taken more risks? Do they sound like a dozen twenty-year-old C86 bands? Did those bands ever write hooks like this?

Skip Perry

13 :: Dirty Projectors

Bitte Orca

(Dead Oceans)

In hindsight, Rise Above (2007) was the Dirty Projectors’ future as filtered through a shattered window: the likeness of a real life popular indie-rock band circa 2007—with all the sprightly West African guitar licks and off-kilter ululations such implies—as presented in fetal bits and pieces. So while that whole (exhausting) exercise felt too disjointed, contrived, and dull to pass as the logical precursor to this, the band’s fawned-over application to a more accessible mainstream niche, on Bitte Orca the band graciously collects and assembles those shards into something that for the first time has some real momentum. There is a palpable go to each song here, replacing fitfully the abstruse ambling of past efforts. This is, finally, the absolute blossoming of the awesome potential David Longstreth and Co. have when focusing their idiosyncratic talents into something cohesive, where each skewed riff and trembling coo is performed not for virtuosity’s sake but in devoted service to the Pop Song.

What’s most interesting about this record, I think, is that the vocal ticks and jarring rhythms that once distracted from the flow of a typical Dirty Projectors track now imbue this otherwise serviceable indie rock with an oddly infectious breadth. Amber Coffman’s serpentine vocal acrobatics on “Stillness Is the Move” and Longstreth’s surprisingly soulful performance on “Temecula Sunrise” aren’t stabs at mainstream R&B crossover fame so much as exciting examples of where art-house indie-rock—and, shockingly, where the band that recorded The Glad Fact (2003)—could go in the next decade.

Traviss Cassidy

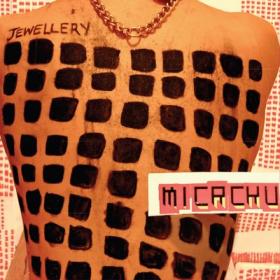

12 :: Micachu & the Shapes

Jewellery

(Rough Trade)

Mica Levi, it should be emphasized, was twenty-one years old when Jewellery was released. Let that roll around in your head for a moment and then listen to the album again—so solid an album that it sounds like a product sweated over for the course of many years and even more failed endeavors. And while much has been made of Matthew Herbert’s involvement and interesting as it is to have a producer of his caliber at the helm of such an exciting young artist’s debut we should not shine too glaring a light on that fact. It detracts somewhat from the fundamental quality of each trinket song: perfectly scoped at two or three minutes in length, perfectly arranged to pack creativity in that minimal space. Herbert may have lent some perspective to Levi and company—he is known for the dense polish and the seeming strategy of the modern pop song—but it’s the “experimental” in Levi’s “experimental pop”—no thoughtless appendage, that—which makes Jewellery so repeatedly listenable. Homemade instruments, UK grime and hip-hop inspired rhythms, buzzing robot melodies…and yet songs like “Curly Teeth,” “Calculator,” and “Lips” still manage to sound less like novelties than exactly what they are supposed to be: distillations of both playfulness and the anxiety of post-adolescence, dynamic and with a great sense of space. Surprisingly light but thoughtfully constructed, Jewellery is the sort of record that wholly owns a kind of natural effervescence that most artists labor to simulate and most sound old failing to achieve.

Conrad Amenta

11 :: Emeralds

What Happened

(No Fun)

Chicagoans cling to their awful winters with a strange vociferousness, but I will fight, even amidst a miserable stab through a negative twenty (with wind chill) morning like last Thursday, in favor of the Biblical severity of Cleveland’s. It is incongruous, disabling, violent stuff. One time I walked into work without a coat and walked out to find two feet of snow smothering the city; my LeSabre fucking swam home that night. Cleveland’s Emeralds sound wholly a product of this place, my birthplace, clearly the cause of some of my affection—and their (our) wintry What Happened feels stuck indoors, the type of lived-in that your living room gets after weeks of dreading going outside.

Which might be why the longest track here is called “Living Room.” Or, as can be the case with droning, obtuse, sine-filled ambient records, I may be reading nostalgia and holiday plans and winter dread (and whatever else) into this hour-long thrush of pill music, of narcotically warm sounds breathing softly into one another. It made Betz think of basketball, for example. The term “ambient” doesn’t in practice reference music that fills our rooms passively but music that breathes life into our thoughts, whatever they are. It’s the breath in our frigid hands, whatever our hands need to be doing. That these five tracks—which suggest something at once organic and wholly digital, taking a lot from of course Whitman’s Lisbon aesthetic but not shirking Hecker’s or Fennesz’s more structurally rigid pieces—coalesce in “Disappearing Ink” into something of an ambient climax is more proof of fact than a post-rockish raison d‘être. And this fact isn’t so much that the stunning confluence of sounds in those final ten minutes are the most important or worthwhile, but that they call attention at last to those same sounds as they had been arranged across the first fifty. Which after a year in its clutches is why I think the title of this record is left blissfully abstruse: What Happened is whatever happened in whatever hour in whichever room. Because what the record reminds us in those final moments is no less than the omnipresent fact that the room itself is alive.