Features | Lists

Unison

By The Staff

Art: Sarah Andreasson

We’re back again this year-end with a tradition we began when 2014 came to a close—in keeping with Cokemachineglow’s long-simmering distaste with the notion of assigning inevitably reductive numerical scores to works of music (no hate to those who do, but have you considered, y’know, not?), we introduced Unison/Harmony, our unranked list of the staff’s consensus favs (Unison) and individual writers’ loves (Harmony). We’ve done it again, because we’re consistent, but first we have something we need to tell you.

And, yikes, this is hard.

In 2002, our inveterate Editor-in-Chief, Scott Reid, first unearthed from the frozen depths of Somewhere in Canada the golden-plated book that instructed him from on high to found Cokemachineglow. Since then, a lot has happened: we’ve been threatened bodily harm by at least three artists on separate occasions; we’ve been indexed on and later unceremoniously removed by Metacritic; some of us have married (not to each other, though I’ve eyes on Toph), and some of us have children; Robin Smith was born; we’ve booted Sufjan Stevens off of untold numbers of year-end lists.

In other words, things have changed. For us, and for music criticism, for the internet, for the Glow mansion (new sconces!). CMG has always existed as a labor of love, which is a euphemism for “we’ve never made any money from doing this.” As someone who discovered the Glow in its nascent years, read it faithfully forever after, had posters of Dom on his dorm room walls, applied to write here for years and finally made it onto the staff late in the site’s history, I look at that history—of staying ruthlessly independent and flat broke—as one of our crowning achievements. In the end, we’ve always done this on our terms. We’ve answered to no one but God (Carey Mercer) and Mark (who built the site, and who tells us that, no, we don’t have the technology to publish a Yeezus review that’s just a finger flicking Kanye’s earlobe forever, into eternity).

And that’s why, with heavy hearts, we’ve collectively decided our 2015 year-end coverage will be the last writing published on Cokemachineglow. It’s time. We’re going out with dignity, however impossible that seems for a website with me, Corey, on staff. We want to thank you, more than we know how to do, for reading over the years, for commenting, for emailing, for being there. The Glow has always been the ultimate writer’s space—something Scott has fostered, and something our independence has allowed to flourish. But that means the Glow has always been a readers’ space, too. No ads are driving traffic here, we’re not name-checked on any Netflix original series, Wikipedia won’t even let us confirm our very existence. You come here because you find something of value in our strange, sometimes self-indulgent, always open-hearted scribblings.

Thank you.

We’re bowing out now because we’d rather have a decisive end, something of closure, rather than let our home here slowly fall into disrepair while life gets in the way. In the coming weeks we’ll be doing a few other final things, including a CMG Reader, a compendium of our favorite pieces through the years.

For now, though, we’ll get things started with Unison/Harmony 2015. Unison, the ten records that most reflect our staff’s consensus favorites of the year, should give you the best sense of the soundtrack to CMG’s final year. Harmony, where individual staffers write about albums from the year that meant something to them, broadens the scope. And our individual staff lists round out the coverage. Like last year, I’ve made a Spotify Unison/Harmony playlist, for your shuffling pleasures, which you can find here.

Thanks for sticking with us. Let’s make some words about sounds now.

******

Grimes

Art Angels

(4AD)

“There is harmony in everything,” sings Claire Boucher on the year’s best pop record, one obsessed with finding that harmony amidst the dissonance of dozens of stylistic reference points bumping up against one another. Listening to Art Angels, you can believe her. The rap-rock touches of “Kill V. Maim,” the acoustic electropop concoction of “California,” the drum’n’bass rumblings beneath “Venus Fly,” the lite-house bliss of “Butterfly,” and, let me just mention this again, the rap-rock touches of “Kill V. Maim”—these influences run the gamut from zeitgeist cool to seriously unfashionable, and part of the fun comes in testing your own reactions to the individual ingredients in Boucher’s musical polyglot stew. Does the Sugar-Ray-ass riff in “Butterfly” make you want to turn it down so your roommate doesn’t think you’ve gone soft in your old age? Can you blare “California“’s slightly queasy, half-a-quaalude singalong without feeling compelled to explain that, you know, it’s supposed to sound that way?

In other words, Art Angels is something of a paradox—a pop album that seeks to unify everything in Boucher’s gaze under one beautifully approachable, spectacularly weird tent while also trolling its listeners for their potential prejudices against a whole slew of sincerely uncool ‘90s pop, R&B, and alt-rock sounds. To embrace Art Angels, plenty of listeners—myself way, way included—have to confront their own elitism or snobbishness, admitting that, hey, Aqua actually had some pretty cool ideas. It’s that epicurean spirit, alongside Grimes’s explicit challenge to the notion that record production is a dude’s game, that shows Boucher’s genius (and that’s the word for her) in its virtuosic sweep. She’s interrogating the boundaries we construct around pop music, exploding our notions of who’s allowed to participate in creating it and what sounds have enough caché to be included. And she’s doing it all while writing some of the most gorgeous, moving, and fun pop music in years. Visions is right.

Corey Beasley

Holly Herndon

Platform

(4AD)

This is the sound of Holly Herndon crowdsourcing herself. Privacy, Platform proclaims, is a thing of the past—irrevocably lost to the bowels of social media and the NSA, for example, you best get used to the idea of losing “you.” On “Home” she sings, “I know that you know me better than I know me,” and this is her understanding that, connected as we each are to all things, our lives little more than illusions of agency, there isn’t much that we can provide the universe anymore care of our own devices. Instead, we’ve already done so unwillingly, unknowingly, our lives—our whole fucking idea of who and what we are—recorded in detail and stored somewhere seemingly light years outside of our selves. We build ourselves in tandem: as we record everything that we do (the food we eat, the places we go, the music we listen to, the books we read, the movies we see, the people whose time we indulge, the people whose time indulges us) so are we recorded, and together all of that data somehow amounts to a “me.” There is no such thing as a “soul” anymore, there is just a sweet mess of hyper-specific statistics and goo encased within a fried tube—we are the walking mozzarella sticks of the cosmos.

The indelible beauty of Platform, Herndon’s second full-length album, is in how optimistic the musician seems to be about the loss of self. It’s only natural. In fact, she makes it clear that any “solo” endeavor is typically far from that: a “solo” record is usually a branding exercise in isolation, all ideas and music and inspiration and art supposedly conjured up as if from the natural galactic core of oneself, borne from nothing into everything. Herndon admits nothing of the sort—instead, she finds no lines between inspiration and contribution, between actually hearing someone else on the record and sensing another. Any piece of art is one point, one plot on a continuum which stretches forever in opposite directions, and the artist the vessel for all the actions and stimuli and mysterious essences used to pin that point to a timeline. So when Herndon makes weirdo club music, she isn’t simply escaping her electronic dance roots, she’s re-contextualizing this inherently social music in a new social setting. How else, she asks, can dance music bring us together? Truly: How can the music of Platform bring “us” from the disparate pieces of that continuum into one unified point?

I think her answer is to try everything. Which is why there’s a sort of musique concrete commercial-scape hybridized with an ASMR (autonomous sensory meridian response) track, featuring the closest thing the micro-genre has to a star, Claire Tolan. In “Lonely at the Top,” Tolan’s voice is intended to soothe, sure—but more than that, it’s meant to teach you how to tingle. ASMR transforms “domestic” or commonplace sounds (typing, low humming, water droplets) into (typically TouTube) tracks, and on Platform Herndon employs ASMR as a way to demonstrate that the Internet—the overwhelming interconnectivity of it all—can actually help, can simultaneously oppress and offer a bit of respite from the oppression. That Tolan’s words resemble a corporate self-help guru providing a too-friendly massage makes Herndon’s intent even more fascinating. It’s all here: creepiness, discomfort, rest, titillation, sterility—proving that one’s engagement with the web need not be passive, or even just cerebral. You can feel something here.

Still, Platform isn’t all about concept—to wallow in cool-seeming brain games would be to go against the accessibility of what she does, which would make the whole point of her album pretty suspect. It’s not anything you’ll ever hear next to Drake or Rihanna or Future on any playlist—let alone on the radio—but buried beneath the heaps of blips and detritus of daily chores lay choral melodies and astoundingly gorgeous arrangements. These she fracks out, extracting them by pushing more and more extraneous rubble into each song’s belly, waiting for fissures to emerge and the pressure to bloat to such a point as to allow release to happen—naturally and all on its own. “Chorus,” which may be the only song this year able to dredge up something primordially goosepimply in me, is a subterranean river of raging garbage—literally the sounds culled from Herndon’s laptop, the ambience of her everyday Internet usage, the stuff we hear but always ignore—until it isn’t, the surface of email dings and emptying trashcans pierced, a geyser of something sweet and pure splurging from its compact core. But seriously, if you haven’t heard this song, go: Stop reading and find it and listen. If you are unable to cry at the chorus—and, yeah, the title of the track is quiet little joke about how the whole track is organized—you are made of harsher stuff than me. How else should anyone respond to such beauty at the heart of the mundane, forgettable junk we each perform every single day?

Elsewhere, songs shake with intimate, carnal glee. Vocalists Amanda deBoer, Stef Caers, and Colin Self appear throughout, and it’s to Herndon’s credit that even a male voice can vibrate at its edges with such inability to contain itself that every voice sounds as if it could be a manipulated piece or wavelength from her own. To be honest, it wasn’t long after listening to Platform over and over that I finally parsed apart its credits, which revealed a small but prolific gang of collaborators. Spencer Longo supplied the lopsided tone poem for “Locker Leak,” while Herdon’s partner, Matt Dryhurst, has his coding pawprints all over the place. Let alone that so many cuts from so many tracks—the ecclesiastical climax of “Unequal”; the monastic seriousness of “Morning Sun” pebbling apart until its something altogether giggly; the unnerving breadth of “Home,” and of the nightmare it makes feel so lush—so much of Platform sounds fully realized. Complete. Here, in this particular spot, Holly Herndon builds herself, and meanwhile she’s built, by people she loves, people she respects, people she hardly knows—each individual giving over something crucial to him- or herself. It’s all so fascinating, so inspiring, witnessing this happen—knowing that even if there’s no such thing as a soul, there are many things, many soulful things, that we don’t need to keep from each other anymore.

Dom Sinacola

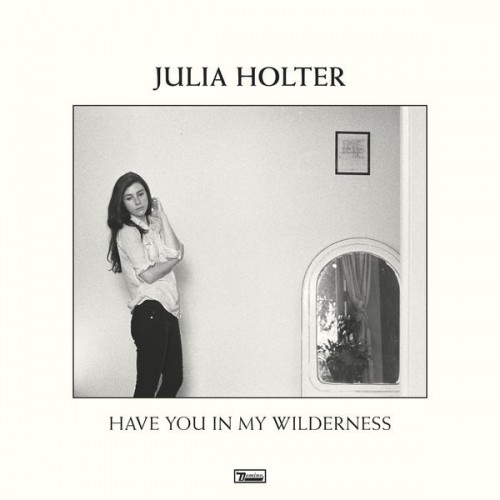

Julia Holter

Have You in My Wilderness

(Domino)

Dim lights on stage. The audience knows the voice, the whisper, before they see the face. It’s the woman of many hats. Then, a hospital bed. Fragments zoomed in on, now beyond recognition.

It’s a rehearsal for a musical. Tap dancers soft-shoe across the stage. The director has them repeat the routine, over and over, slower each time. The voice the audience knows emerges from a whisper, forms words, pre-melody. The bed is an island, with a single palm tree. A traffic cop blows a whistle. It’s London. A double-decker bus passes. The tourists aboard take pictures of her, marooned.

Red carpet rolls out. Cameras flash. It’s George Gershwin and Charles Ives, only top hats visible above the glare. The bed melts into a rainy street. She asks for a cigarette. Three years pass. A collapse. The man pulls out a lighter. Their children run circles around them as they embrace. Director yells cut again.

John Wayne takes the cigarette from the woman’s lips and stubs it out on the desert floor. Saxophones play in a row. Someone forgets his cue. They whistle. An imperious glance. Someone calls, “Bandido.” She responds? His hands are hers, anticipating her movements on the piano. She finally sings. Crashes of plates from the kitchen drown it out.

A road stretches into a cardboard sunset. She calls out, “Line.” The audience shuffles uncomfortably. Murmurs. Chairs squeak. Someone finds a viola under his seat. Plays her dinner music. She orders a fresher perspective. The waiter brings a rattlesnake. A gun goes off. False start. Everyone slowly walks back. She retires. The reviews rave.

She goes home. It is a museum. Sonic Youth are there. And Gigi. Women named Lucette, and Betsy. Impossible women, behind glass. Dan Bejar takes notes, then methodically burns them by holding them over a candle flame. Kate Bush stands on the edge of a cliff, kicking pebbles down. The glass breaks. The wax runs.

Applause. Polite filing out of bodies into the street. A single light, backstage. Make-up smears, wigs and canes fuddle and clatter. A series of faces molded onto hooks. She returns hers. Goddess eyes remain, locked in a frozen stare. Still someone else’s dream. A wilderness grows around her, alone.

Tell me, why do I feel you running away?

Curtains.

Joel Elliott

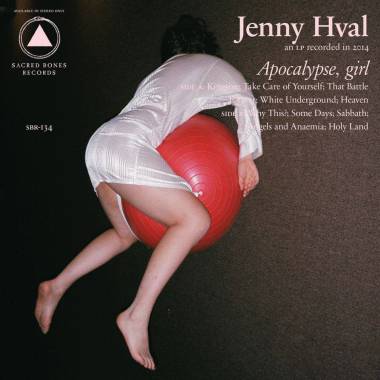

Jenny Hval

Apocalypse, girl

(Sacred Bones)

Apocalypse, girl is a confluence of impossible becomings: “I said, if the dog was a wolf and I a boy she could be a horse, sure thing, she had no excuse…” Here, Jenny Hval becomes a little girl, who becomes a boy in the proximity of a wolf; Hval becomes an angel, who touches a little boy and turns him into a girl. Jenny Hval, the body, becomes death—but in a decidedly un-Zemeckis way. (Meryl Streep would kill to have this poise.) In her own annotations for “Heaven” on Genius, Hval writes that “so much music is about the death drive—maybe all music.” One of the conceits of Apocalypse, girl is that this drive belongs not just to the individual, but to culture and all its appendages—including the ones that cry out to be amputated. Who better than the poetess laureate of the post-digital body to guide us willingly past the end of history, only to show us that history just began? “This is what happens on the edge of history: the Great Eye turns to us.” And we find that we are naked, but unashamed.

As one finds her on the brink of this apocalypse of the new, it is somewhat startling to find Hval’s work taking a decidedly religious turn. But Hval is never quite as transgressive as she seems, or rather, her singular transgression is the adoption of a materialist naiveté that obviates the need for explicit destruction. Her ideal narrator: a child asking all the hard questions on Sunday morning, but talking out of her vagina. Jenny Hval wants to show us the way to a new heaven, where bodies are hung up like costumes and disfigured angels serve spirits that are actually spirits. Where is this new, inverted heaven? “Nowhere in particular,” no doubt. And this absence is what makes it universal. Anywhere the divine touches down, it sets limits for itself; better to become, to break open the limits and communicate. Better to touch, to hold, behold, be held. And if this leads us, not to a “White Underground,” but to the black summit at the edge of nothing—the Great Eye still turns. Maybe this time, it will like what it sees.

Brent Ables

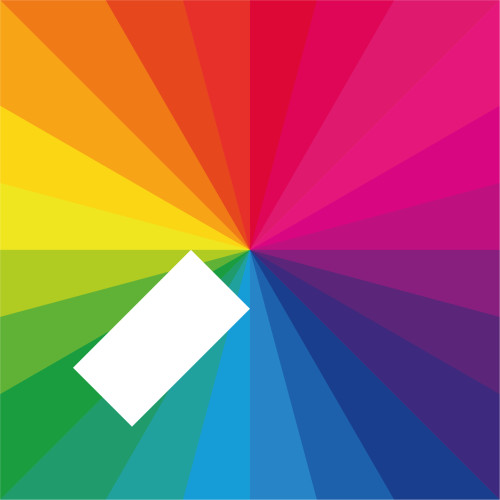

Jamie xx

In Colour

(Young Turks)

Music is a blessing. That’s pretty much been the simple sum of my whole critical aim, saying that. I say it over and over again. I say it in mildly different manners, sure, but if you’ve read any of my stuff here or elsewhere then you’ve read plenty of Betz doing Betz. If I’m not talking about rap then you can tell when I really love something because I find a way to start talking about Tarkovsky or Cronenberg. I’m obsessed with Boethius’s concept of the eternal moment; I also pretend that everyone else had the same Intro to Philosophy class that I did in college. “Music of the spheres”—into it, big time, I’m an absolute ideal-chaser if ever there was one. And Keats’ whole thing about truth is beauty and beauty truth? Yeah, that’s my steez. I get on that Bible tip, too, Old Testament-style, in case you find your music reviews wanting for mentions of Eden and capital-F floods and, my favorite: living sacrifice.

It’s fitting that my last blurb for the Glow is “about” (yes, using that word loosely here) a record I already reviewed for the Glow because, like, at a certain point aren’t we all just doomed to repeat ourselves? They say history does it, and aren’t we the ones writing it? I’m 33. I’m starting to settle in my ways, no doubt: neck-deep in the solidification phase and probably just another Kanye West release away from petrification. I am crossing that threshold point where one finds their identity—or it finds them. Growth still happens, and new challenges and struggles pour over you like a storm, weathering and eroding you, whereas new blessings (my third child is nigh) radiate upon you and you bask in them until your skin is flaking off. These things interact with the core of you, they speak to it and teach it and fuel it—but they can’t change it. They only seek to expose it more.

I have to talk about this record indirectly because I said pretty much every direct thing I wanted to say about it in my review. Well, except for the way “Sleep Sound” somehow manages the paradox of seamless contrast and pliant derivation in its segue to “See Saw,” a fact that was pointed out in the comments section of the review by dear reader Caleb. It’s a transition like beatitude, the persistence or survival of an idea through modest variance. Doomed to repeat, blessed to repeat, to manifest anew what’s just an altered version of the old, since—like the Good Book says—there’s nothing new under the sun.

At this point you’re begging me to say something, fucking anything, about the music here. Sorry, I can barely help myself: these are the things I think about, the things I feel, when I listen to In Colour the collection of music. These are the parts of myself that this music reflects back to me. If that sounds horribly insular and self-absorbed, know that I’m equally eager to hear about what this music reflects back to you, readers, just as I was to be reminded by Caleb about “Sleep Sound”/“See Saw.” For this is the perfect type of music to evaluate as we will and then compare, thus exposing ourselves in the process. Magnanimously, Jamie xx gives us canvases that are wide, impressionistic, non-deterministic, largely free of built-in associations, aching with a very pure sort of inspiration, a very open absence of an overriding thought, a very warm invitation for our spirits to step in, to mingle, to dance into the night, and in the dawn to talk about who we are. We let our clothes lay on the floor, and we could let them lay there forever.

“Gosh” and “Hold Tight” stumble briefly towards their identities before gripping onto them, settling into their grooves, and what are grooves but musical metaphors for finding beauty in life’s grind (and/or about sex)? And upon those grinds these tracks impose and layer elements that elevate, carrying higher forms in the cars above the rumble of the tracks, melodic and harmonic ideas that feel born from a train of thought with a perpetual motion engine, gliding on through a wasteland it can barely see. Its undying momentum transforms its perception into an approximation of contentment and sometimes even bliss, even as it runs on a track that runs round a barren world (yes, I know you’ve seen this movie, but at least it’s not Tarkovsky). In its best moments In Colour vividly illustrates how gracefully taut the tension, how sophisticated the symbiosis between entelechy and evolution. The more things change the more they stay the same, right, to put it crudely. It’s a theme I’m well familiar with; I wrote a play in school about it. Now, a dozen-plus years later, here’s my epilogue. If I ever take a bow, it’ll be to the celestial dolphin splash ‘n’ twirl of “The Rest is Noise.”

As we talk about momentum through wastelands, I recall Kaylen Hann’s excellent Unison blurb for You’re Dead! last year, where she framed Flying Lotus’s portrait of mortality in terms of velocity and acceleration. Let me tell you, having kids, I am now very fucking aware of the speed of my own mortality, and life is a highway in every way except the way Sheryl Crow meant it.

For lack of circulation my foot is dead-lead on the pedal; the signs become indecipherable, momentary blobs of green and yellow. The radio is playing, non-stop hits, “the ’80s, ’90s, and Today,” whatever “Today” is. In the back my kids are crying in their car seats, then fighting over the DS, then sullen teenagers on their phones, and…silent. I glance over my shoulder; their seats are empty. I look ahead and now everything’s whipping by so fast the texture of it is incoherent, like racing on the original Playstation. The radio’s static. I slump over the wheel. I dream my vehicle has wings. No, rockets. No, a warp engine. We’re all in it, we all share this intergalactic lifeboat on its way to a massive, massless whirlpool. You’re there, too. But the boat’s gone. As you speed through space towards a destination you’re not sure you want to reach, the stars streak, refracted and smudged into a vortex of color. Soon there is no external relation to judge one’s movement or place by. Are you even moving now, really? Does it matter? In this Colour your extraneous self is stripped away. There’s such a glow. And the glow is from what’s left of you…a gleaming, dying spark, wherein all emotion and thought are blurred into one ambivalent charge. Young Thug’s here, too, but ignore that for the moment. A moment which, by the way, might be eternal, if time really can slow down to a virtual stop. And the secret you discover now is this: the music of the spheres is the music of being. Music speaks to that music, as deep cries out to deep (heyo, Bible reference #2). So I guess I truly am doomed/destined to repeat myself, again and again and again: music is a blessing. Be blessed.

Chet Betz

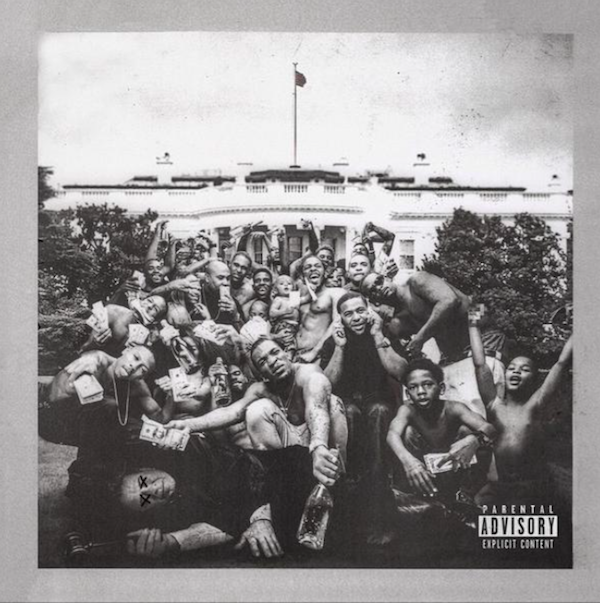

Kendrick Lamar

To Pimp a Butterfly

(Interscope/Aftermath/Top Dawg)

The first time I heard Tupac Shakur’s voice on To Pimp a Butterfly, part of me thought Kendrick Lamar had done it: he’d found Tupac Island and secured an audience with the legend himself. Lamar had poured eight albums’ worth of anxiety, dread, and anger into topics which often don’t rationally cohere—moments before he interviews Pac in “Mortal Man,” he spits a line against Michael Jackson’s critics that is so savage you forget that believing the child molestation charges levied against him isn’t exactly on the same level as the white supremacy and internecine gang violence he eviscerated in the album’s previous song—but it all hangs together because, Jesus Christ, Kendrick raps like no one who’s come before him. Not so much a manifesto as it is Public Enemy’s “Welcome to the Terrordome” spread out over 80 minutes, it works because he is just that pissed off.

No honest person can blame him. 2015 wrap-ups are, correctly, pointing out what a dreadful year it’s been for the US body politic. Many are also noting that it came on the heels of an especially poor 2014, when even the indomitable Killer Mike had to summon the courage to admit that the bloviating, prevaricating nonsense the St. Louis County prosecutor used to exonerate Mike Brown’s murderer made him feel like less of a “champion”—that it made him feel like something less than Killer Mike, less than human, which is of course the design of a system that goes to great lengths to sanction the extra-judicial murder of black men, which is, in the final analysis, perhaps not extra-judicial at all. Like global warming, the situation is only getting worse, and, also like global warming, the response of elected officials has been to hunker down and do nothing. At this time of writing, the streets of Chicago, my adopted city, are seething with anger at the shooting of Laquan McDonald. Calls for the resignation of Rahm Emanuel are brushed off by the presumptive Democratic Presidential nominee (and longtime ally) Hillary Clinton.

But from adversity comes true courage and greatness: Black Lives Matter. That something like this can emerge out of some horrid millenarian conditions reminds one that maybe life is worth living. Accordingly, they’ve adopted “Alright,” the single from To Pimp a Butterfly that put lie to the notion that this album was radio-poison. I thought of this often those three weeks in March when the album never left headphones, or car stereo, or internal cerebral radio. I thought, I can’t be the only one driven into righteous head-thumping by the hook of “Hood Politics”; the only one so moved by the slinky-yet-paranoid slither of “Institutionalized” that I’m right at those BET awards with Lamar and his companion, awed one second, jealous the other, in thrall to the voice of Snoop Dogg of All Fucking People less as wizened narrator and more like some sort of sardonic Gospel chorus; who strutted along to the G-funk of “King Kunta” unthreatened by the sirens in the song (first as a dull roar in the cluster-chord in the second chorus, than blaring out in all its distorted saw-tooth wave glory at the outro); who had to wipe something close to a tear from his eye because Ronald Isley’s final sung verse in “How Much a Dollar Cost” said more about the nature of hard work and little reward than anything I had seen with my eyes, let alone could write.

The record of 2015, clearly, is To Pimp a Butterfly. No other record speaks so passionately, and so well, about topics that are so current. I will add the caveat that I’m interested in seeing how its reputation fares through the years: Lamar’s espousing of positions that are close to “respectability politics” is an issue worth debating, but it’s a debate in which this white writer would only be unhelpful. One thing that strikes me, though, is that a lot of this album’s conceits are just plain goofy when taken individually: God as a homeless man asks a wealthy man for money; the personification of the devil that tempts consciousness-minded rappers is actually fucking named “Lucy”; the poem to Tupac that doubles as the narrative structure of the album is really lame and tiresome after the fifth time. Lamar struggles with the role of generational voice, and while it animates the lump of steel in his heart (and, by extension, the words out of his mouth), he also very clearly wants the job, demanding the audience come up to the front of the stage in the (exhilarating, amazing, absolutely essential) live version of “i,” before breaking up a fight to sermonize. This makes the closing conversation, where he desperately wants Pac to pass the torch, somewhat troubling to consider—not least because he lets a dead man murder him on his own shit, Shakur’s sobering observation that we rap to tell the stories of “our dead homies” saying even more than album highlight “Hood Politics,” which uses the same notion as part of its hook.

But Pac can’t answer, of course, which is how the album really closes. Turns out the dead heroes of the past can offer much, but the torch can’t be passed. Pac was murdered: that torch was dropped. It’s up to Lamar to pick it up and carry it—that is, to work. To struggle. Besides, Lamar’s no dummy (as in that moment when Shakur drops that bomb, where all the young Compton MC can do to respond is simply mutter “damn”; best simply to acknowledge it and move on). He’s said at length how the album was explicitly designed as something to be taught in high schools along To Kill a Mockingbird. Maybe the depths of its allusions and metaphors aren’t quite on the level of Ellison’s Invisible Man, but it should also be said the book doesn’t have anything as thrilling as “The Blacker the Berry,” or that even the book’s love of Satchmo is nothing on the Complete History of African-American Music 1915-2015 that is on offer throughout this album. It provokes by design.* And, if nothing else, it insists that if true justice really existed, if “critics wanna talk like they miss when hip-hop was rapping, motherfucker,” then “Killer Mike would be platinum.” That’s something I’ll always cosign.

*(If this 35-year-old underemployed failed musician who has yet to know a deadline he can meet and has therefore made exactly $50 from writing about music over ten years can offer any final kind of advice to those looking to do the same, it would be that when a record wants to talk to you, try and talk back to it. And also: music can encompass something as profound as this album and as gleefully silly and over the top as, say, Rihanna’s “Bitch Better Have My Money,” with every feeling on earth in between—this is exactly why the damn medium is so sacred, and fighting about it and overthinking it has always been my way of honoring it, so do what you can to honor it too.)

Christopher Alexander

Main Attrakionz

808s & Dark Grapes III

(Vapor)

One of the great clichés in rap writing is to label an emcee “weary,” but it’s hard to find a better descriptor for Main Attrakionz emcees Mondre M.A.N. and Squadda B, who, on their umpteenth album 808s & Dark Grapes III, sound straight-up aggrieved. It’s not just their lyrics, which range in brightness from cautious optimism (“Shoot the Dice”) to melancholy nostalgia (“Summa Time”), it’s their tone, the way they trudge, sludge-like, through their verses, or weep the hooks, or sorta moan their come-ons, or hit at sibilant triple-time crescendoes like their fucking lives depended on it. This is a duo who can exclaim, “Fuck it, let’s keep it going ‘til the sun come up!”, and sound like they’re holding back tears while doing so. They are both like 23, and they have sounded this way since at least 2009.

They have also, since they first emerged in 2009, sounded uniquely, almost sociologically aware of themselves, their lives, their surroundings, and their futures, and have curated a sound that communicates this milieu in airy, plush synths, skittering cymbals, and deep, underwater piano chords. No producer has helped them in these efforts more than the California duo Friendzone, who created the signature Main Attrakionz tracks “Perfect Skies” and “Chuch” on 808s & Dark Grapes II (2011), and were tapped to produce every second of this, its successor. But something strange happened in the intervening years. Mondre and Shady went deeper into their hole—got more patient, more dour, more (yeah) weary—but Friendzone’s glitchy, environmental music found its focus. These aren’t the off-hue airways of before but instead great, neon cityscapes, full of arching alien synth lines and detailed, 4K boroughs, at once lived-in and impossibly clean: Neo-Tokyo, saturation turned up until the knob breaks off. The contrast between Friendzone’s crystalline music and Main Attrakionz’ baleful vocal performance is striking but subtle, lasting and somehow wholly new, doing for hip-hop what William Gibson did for punk.

Clayton Purdom

Oneohtrix Point Never

Garden of Delete

(Warp)

Garden of Delete is no mere byproduct of its age, but a living, breathing rejoinder to the very infrastructure of that age, to that infrastructure’s every component part, articulated via a digital mainframe with no regard for prescribed notions of high and low culture, classic or contemporary trends, the artistically inclined or the atavistically indulgent. It’s Daniel Lopatin’s nü-metal album, his grunge album, his prog album, his EDM album, his soft rock album—it’s none of those and all of them at once. This garden’s soil is ripe with nutrients, with dense roots and hearty saplings extending forth in either direction. No ground is left untilled. Finding your way through the album’s labyrinth of sonic detail, down its vast lyrical and thematic avenues, and across its elaborate extra-musical frontiers is all part of the experience. But in no way are its pleasures bound to these concepts. Instead, what Lopatin has emerged with is a truly modern piece of audio-visual art, a choose-your-own-adventure narrative in which our hero––an adolescent alien named Ezra whose attempts at crossing a kind of metaphysical threshold toward enlightenment are echoed by the at once gauzey and garish textures Lopatin so casually employs––is both a figure of identification, a figment of shared nostalgia, and a manifestation of anxieties long-thought conquered.

Lopatin has spoken of contemporary electronic music’s influence on the album, as well as the unconscious imprint left by unlikely compatriots and tourmates Nine Inch Nails. But, while much big-tent electronic music is essentially dated on arrival, for Garden of Delete Lopatin has built unfashionable reference points (including NIN) into its very DNA. The record espouses reverence to no particular era, but rather individual moments one might readily, if hazily, recall from a time when acronyms such as AM, FM, MOR, and MTV still has real world caché. Lopatin’s aesthetic palette reflects such diversity; it’s both his most expansive and most intimate record yet, folding in classical instruments (guitar, piano, organ, strings) that nonetheless sound sourced from the memory bank of an unidentified Woodstock ‘99 casualty.

Then, it’s no surprise that Garden of Delete is easily his most song-oriented album, and yet I can’t begin to accurately describe exactly how Lopatin has constructed any given passage, or confirm whether the acoustic sounds are synthetically rendered, or if the synthetic sounds are acoustically treated. “Sticky Drama,” with its blast beat percussion and chipmunk harmonies, sounds like arena-ready metal mashed up with the theme song from a Saturday morning cartoon. “Freaky Eyes” percolates like EDM by way of the Graveface catalogue. “I Bite Through It” lurches like a post-rock guitarist attempting to play along with a vintage prog record as it skips asynchronously on the hi-fi in an adjacent room. Which is to say, Garden of Delete is a lot like memory itself: nebulous, volatile, contradictory. That it all works and is, in fact, Lopatin’s most personal and provocative statement to date is proof not simply of a restlessly artistic mind, but of a musician whose world-building aspirations never betray the humorous and vaguely hedonistic spirit of creating art in one’s own image. GoD, indeed.

Jordan Cronk

Vince Staples

Summertime '06

(Def Jam)

The sentiment driving 2015’s other universally acclaimed rap record is about as far as you can get from “We gon’ be alright.” Summertime ’06 paints the Long Beach of ten years ago as a nihilist’s diorama, a pitch dark vision of drugs, death, withdrawal, death, sex, and death. Vince Staples would’ve been about 12 years-old that summer, but across the twenty tracks of his did-you-fucking-hear-that riveting LP, he sounds either ageless or aged a few centuries beyond his time, an oracle spitting forth decades’ worth of pent-up bile, half from his own rotting guts and half spewed into his mouth by the untold number of systems rigged against young black men in America.

But OK, that’s putting too fine a point on it. Staples could give a fuck about being the “voice of a generation” or whatever such self-aggrandizing bullshit. Fair enough. Even if you reel in the self-satisfying reflex to take the record as a sociology thesis set to beats, Summertime still works as a grand statement of a different sort. It paints with pinprick detail a picture of adolescent life, strewn with the lust and aggression and ambition and frustration of those years—only in Staples’ experience that means those feelings get tossed up against a backdrop of drug-dealing and dead-eyed violence which, of course, makes them all the more potent.

And more frightening. Because Summertime, beneath all of its crisply seething beats and sneaking hooks, is a fucking terrifying record. It’s supposed to be. Staples investigates fear throughout the album’s 60-ish minutes—the fear of realizing your country either doesn’t care if you die or would actively prefer it if you do (“Lift Me Up”), the fear of realizing the escape offered by drugs won’t work forever (“Jump Off the Roof”), the fear you can inject into someone else’s mind by presenting yourself as fearless and the lingering fear of enjoying that power (“Norf Norf”), the fear that, yeah, “this could be forever, baby” (“Summertime”). That’s the sentiment driving Summertime ’06, the fear of the choice you have between drowning in the void or laughing alongside it, and the fear that it might all be for nothing.

Corey Beasley

Viet Cong

Viet Cong

(Jagjaguwar/Flemish Eye)

I was fortunate to catch a Viet Cong set in Brooklyn this past June. It was an unfailingly energetic rock show culminating in the most cathartic bout of headbanging in which I’ve participated this year—which was unsurprising. But what was completely unexpected? They told jokes! Vocalist/bassist Matt Flegel made a concerted attempt to be funny between songs, something of a relief for a band so seemingly obsessed with death, the inevitability of aging into that death, and torrents of existential despair. Listening to their debut album, one almost expects the band to completely self-implode from nervous intensity, leaving only a sole full length to be unearthed by some future Lenny Kaye in 2035.

Viet Cong traffic in a brand of shadowy, psychedelic post-punk driven by a thunderous rhythm section. I’m told it still sounded pretty awesome at SXSW when drummer Mike Wallace broke his arm and was required to drum Rick Allen-style, until being assisted by Swans drummer/carpenter/viking Thor Harris on second-arm duties, resulting in a supergroup for the ages that the ages will most likely never be able to enjoy. Such is the fleetingly sad nature of existence: Suitably, the lyrics on this album, when you can make them out, read somewhere between dour and despairing, perhaps befitting a band containing two ex-members of the Calgary based Women, who allegedly called it quits after an onstage fist fight and whose guitarist, Christopher Reimer, died in his sleep at the age of 26. Joy Division comes to mind as an easy point of comparison, but Viet Cong are both closer in sound and in spirit to British art-punkers This Heat. And if you (correctly) believe their Deceit (1981) an overlooked masterpiece ripe for re-evaluation, you should really listen to Viet Cong as soon as possible.

Chunky bass lines with that vintage Peter Hook sound? Shimmering psychedelic passages? Krautrock repetition bordering on a test of one’s endurance? Apocalyptic drums resembling a billy club beating to death an empty trash can? Oh, yes please: all of it. Viet Cong even play the role of jam band on the fittingly titled “Death,” the album-closing, eleven-minute Krautrock epic that serves as a microcosm of every style the band touches on earlier in the album, its repetitive middle section’s guitar-and-cymbal caterwaul akin to having one’s head slammed into a wall over and over again. “Death” has been known to stretch up to seventeen minutes at Viet Cong’s live shows, and nearly always as a set closer, with no encore. None is necessary. It would cheapen the effect. It would cheapen the efficiency. It would cheapen the pain of each second’s blow.

For many people, the band was rightly taken to task over their chosen moniker, which brought Viet Cong more press in the second half of 2015 than their music did. CMG scribe Brent Ables already went into detail in this matter here, but suffice to say, they’ve formally apologized and they’re changing their name as we speak (and have in many cities placed as “The Band Formerly Known As Viet Cong”), to rise yet again from the ashes in the near future. Meanwhile, we should return to the music—to the frantic “Silhouettes,” to Matt Flegel as he happily(?) details “another book of things to forget / an overwhelming sense of regret.” Luckily, it’s FKA Viet Cong’s m.o.: furious rock music can make the “poisonous precedence [of a] pointless experience” far easier to stomach, and far likelier to forgive should they mess up and fall apart all over again.