Features | Lists

By The Staff

Noah23

Street Astrology

(Self-released)

Forget Run the Jewels 2: this is the best hip-hop album of 2014. It’s brighter, bolder, and ballsier than any other entry in the genre this year. Not because it’s so “hard,” or whatever; the most aggressive lines on the album, from “Tearz in Heaven,” are directed at Eric Clapton and his deceased son. It’s bold because, in classic Noah23 fashion, it bucks trends by refusing to adhere to any one style or approach in order to produce its complex effect, and because it integrates a set of deeply personal experiences into a universally accessible work of art.

Noah’s the anti-Rick Ross. Instead of building up an elaborate fake mythology, he raps a true story about how “My Mama Bought Me A Nitrous Balloon” and makes it disorienting enough to be believable. But this is no Childish confessional, as the personal is so expertly stitched with the abstract and downright absurd that the listener is too busy sorting out the levels to be caught up in any of them. Like a great postmodern novel, it blends the profane with the profound and ends up somewhere beyond either of them. Street Astrology is complex, occasionally messy, and on one occasion (we’re looking at you, Lil Shark) disastrous. But it is never complacent, not for a second, and that fact alone would distinguish it from 99% of rap albums released on the internet. That it happens to be thrilling, eclectic, exuberant, and often brilliant is a nice bonus.

Brent Ables

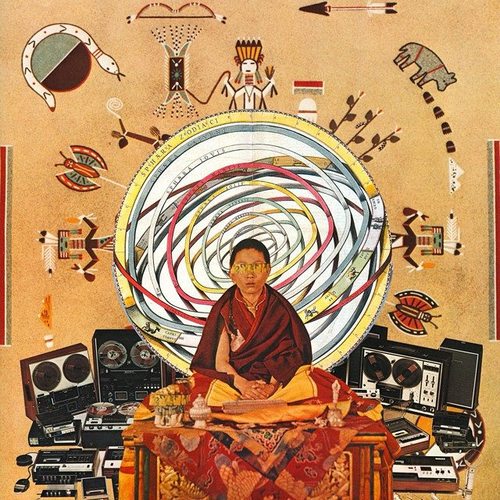

Lydia Ainsworth

Right from Real

(Arbutus)

Maybe the title of Right from Real is just a snappy turn of phrase; I dunno. But the fervor with which Ainsworth collapses different musical techniques together is often breathtaking; saying Right from Real is inspired by the early ’80s requires the caveat that it’s inspired by most of the early ’80s, often at the same time. The fidget-based kineticism of the album suggests Ainsworth is trying to work through the difference the album’s title suggests, as if “right” and “real” aren’t the same thing. In the not quite half-century since postmodernism has been a thing, we’re still trying to figure out the difference. Ainsworth manages to capture a sense of epic intellectual history and immediate praxis; the sheer amount of noise fuels the intensity of half-articulated questions with answers that are possibly too complex to put into words. But most importantly, Ainsworth nails that incredibly difficult balance between electronic experimentation and pop engagement. For all of its obvious touchstones, Right from Real sounds incredibly modern and urgent.

Mark Abraham

Klara Lewis

Ett

(Editions Mego)

Ett’s fascinating for Klara Lewis’ ability to transform noise into grinding rhythms. Simple ideas are compounded through repetition; what starts as a mundane noise is levitated into a propulsive movement as thoughts are connected and blank spaces are filled in. There’s a voice here; a kernel spun out into a variety of gesticulations. There’s also restraint, here. Not every song bursts into motion, as if the conditions have to be perfect for more than a sense of rhythm to occur. In that sense, the tectonic pace and tone of the album seems to acknowledge the scientific odds of what our world is: sometimes movement creates life, and other times life is just an echo that whispers through a cavernous wall of noise.

Mark Abraham

White Lung

Deep Fantasy

(Domino)

If push came to shove I’d probably admit that the White Lung of Sorry (2012) is the White Lung I most adore, but Deep Fantasy doesn’t really abandon Sorry; it’s more accurate to say Deep Fantasy is like 12 Sorrys played simultaneously. There’s a complexity to the record—it is 22 minutes, after all, compared to Sorry’s 19—that is deceptive? Mocking? Bemused? You try to figure it out; it happens too fast for me. But there’s a heft that replaces Sorry’s skittish bravado; Deep Fantasy is thick description of being stabbed in the face with the skyline of a city crane. Etched out, but maybe done on an Etch-A-Sketch; the album simultaneously sounds permanent and like it’s dissolving the moment it connects with your ear. So Deep Fantasy is push and shove, which is the best we can hope for from punk anyways.

Mark Abraham

yMusic

Balance Problems

(New Amsterdam)

yMusic is a 6-piece ensemble that plays modern and postmodern music. They’re real good at it, too. But Balance Problems is something special, I think. It’s a nexus of particular circumstances, or serendipity phrased as minimalist and modern chamber pieces. Something about the combination of elements on this particular album is fascinating. Minimalist music from Nico Muhly sounds completely at peace with more out work by Timo Andres. Son Lux’s production has a lot to do with that ease of passage. He seems particularly adept at capturing my favorite possible thing about violins and clarinets: when they suddenly sound like they’re dying. There’s a vibrancy to Balance Problems that shines even when the tracks are meant to be sparse. This is music that is wildly immersive, and all the more enjoyable for that.

Mark Abraham

Fennesz

Bécs

(Editions Mego)

For almost 20 years now, Christian Fennesz has been quietly laboring away on one of the most consistently enjoyable catalogues of ambient music in existence. It’s shocking, really; in 2014, his output—solo albums, collaborations, as one part of Fenn O’Berg, and soundtracks—rivals any other artist in the genre. It’s hard to keep in perspective how seminal Endless Summer (2001) and Venice (2004) really are, how important his brand of shuddering beauty is to ambient music specifically and the glitch-heavy melodies of today’s music in general.

Does it strain credulity to mention Fennesz in the same breath as My Bloody Valentine? If not for his consistency, I think we might…instead, we are in the luxurious position of being able to take Fennesz, and his remarkable new album, for granted. It’s just more of his casual, ho-hum brilliance, flying under our collective radar. Bécs, like so much of Fennesz’s music, is unassuming, simple, and the product of every decision made perfectly. It’s the masterful product of an impeccable ear for melody and taste for aesthetics.

In other words: it’s just more perfection from an artist who has, for his whole career, seemed to materialize as if from mist and placed his latest offering, fully formed and excellent, down right before our eyes.

Conrad Amenta

Grouper

Ruins

(Kranky)

It’s somewhat surprising to see someone strip away one or two layers of a well-established and respected formula and find even broader universal acclaim underneath, but that’s exactly what’s happened to Liz Harris. Her aesthetic—often removed, ethereal, minimalist—was supposed to be at the center of her songwriting approach. But on Ruins it’s all but gone, leaving lonely pianos or acoustic strums over her voice, which is like a string of energy in space, tingling sub-harmonically, an approximation of a memory of something unclear.

It’s not “found sound,” exactly, but it seems like it could be. One gets the impression of happening across these songs like runes poking out from under sand—old things, simpler things, their craftsmanship apparent. The temptation for anyone writing something as beautiful as “Clearing” must be to drape clumsy string arrangements, backing vocals, bass guitar and dumb drums all over it. Harris, thankfully, doesn’t, and so leaves us with something approaching the singular and unique. Ruins is elegant, sophisticated, and flawless just as it is.

Conrad Amenta

Future Islands

Singles

(4AD)

In my career (L.O.L.) as a music writer, I have written more about Future Islands in the past five years than any other band—literally, thousands and thousands of words. I’m left with just five haikus.

1

Sam danced on TV

People finally got it

Now Mom knows his band

2

William has a stache

And bass riffs like Peter Hook

The secret weapon

3

A feral growl comes

crashing through the melody

Frees you to emote

4

Hardest working band

deserves what it has gotten:

Album of the year

5

Sam does rapping, too

Isn’t that just too crazy?

Singles is real good.

Corey Beasley

Lykke Li

I Never Learn

(LL/Atlantic)

Picture Sweden: uniformly tall, beautiful, blonde people relax in chairs so ergonomic we non-Scandinavians wouldn’t even recognize them as sit-able objects, each Swede dressed immaculately in Fair Isle sweaters and jeans tucked perfectly into boots, comfortable while—in their government-subsidized, envy-of-the-world, humble way—one supermodel engineers a new kind of wheel (is it rounder? smoother? I don’t know, I’m only 1/4th Norwegian) while her supermodel boyfriend tinkers with a plan to make car exhaust transform into clean, pure water to save the world’s children in all colors of the rainbow. Outside, the snow glistens in a calm, confident way.

Then: a dark figure draped in a leather cloak with a black fur hood, a Stygian vision like a blot of ink on a perfect snowfield of white paper, dances into the room. The two perfect, brilliant blondes look up from their work. The figure removes her hood—she, too, is a flawless, CGI-worthy version of human beauty. But on her marble-cut features, a frown, a scowl. Pain. Discontent. “I never learn,” she croons, her voice at once delicate and husky, as she starts her dance again, all balletic movements mixed with spasms of unkempt arrhythmia, as if she’s experiencing a series of tiny electric shocks. Her sadness confuses her compatriots, and they dart nervous glances at one another.

Finally, the engineer speaks from his perch on the Fluufer chair. “Go forth,” he says, “into the world. They need you more than we. They will understand.”

And she does, the cloaked figure, armed with nine diamond-cut molds of heartbreak, thrusting them into our dirty, decadent, non-ergonomic world. We gulp her offerings greedily, as she’s gotten to the cores of us. Come, we say, sit on our uncomfortable chair with us and cry with us into the early morning. We can’t offer you lumbar support, but we can help you stay steady where it counts. (But seriously, can’t someone put a pillow on this thing?)

Corey Beasley

The Twilight Sad

Nobody Wants to Be Here and Nobody Wants to Leave

(FatCat)

I have no idea just how hard James Graham milks his Scottish brogue to maximize the world-weary romanticism in The Twilight Sad’s pitch-black songs, but if you told me dude could get twenty gallons from a single dirt-smeared sheep on a highlands hillside, I’d believe you. Maybe he really does roll every r five times; maybe his o’s really do live right at the tip top of his uvula. If so, I wouldn’t be able to have a conversation with him: ten seconds with Graham’s voice, combined with his deft handling of heartworn melody, is enough to make my eyes tear up as if a gale from the ancient moor—you get the idea. I’ve never been to Scotland. These songs, from a perpetually underappreciated band, are the Twilight Sad’s best, as Graham and guitarist Andy MacFarlane have finally wedded the chilly grandeur of their cult classic debut, Fourteen Autumns & Fifteen Winters (2007), to the expressive, vocal-driven yearning of Forget the Night Ahead (2009) and synth-tinged textures of No One Can Ever Know (2012). The results see the band at the height of its powers, endlessly evocative and soaring into the dark.