Features | Lists

By The Staff

Todd Terje

It's Album Time

(Olsen)

The gestation period is over. It’s Album Time: announced in neon lights, as loud as that leisure suit, presumably worn by one Preben, on album’s cover, who’s already three cocktails-deep in some sleazy Acapulco bar lost in thought, by track three. This is an album not only serious enough about its silliness to be given that title, but also to chant it repeatedly in its simmering intro.

One might reasonably wonder if Terje is playing coy since a good portion of the album re-packages some of his already-known and best-loved material. But those aren’t even the highlights, which belong more to the moments where he escapes his typical mile-high disco for weirder-colored concoctions. See the spaghetti western in space of “Leisure Suit Preben,” drunken Stevie Wonder of “Alfonso Muskedunder,” Final Fantasy with a keytar of “Preben Goes to Acapulco,” or best of all, the insane salsa + beatboxing “Svensk Sas” that somehow manages to beat Chick Corea at his own game. What makes all these tracks stand out is not only how seamlessly they mix with past glories like “Inspector Norse,” but how they expand those more techno-oriented tracks into something that more closely resembles an absurd, cross-genre film score from the ‘70s. Terje has the sonic diversity of a gonzo producer, the compositional intuition of a composer, and the chops of a seasoned session player.

But what to make of the cover of Robert Palmer’s “Johnny and Mary” right in the middle, which is, depending on who you ask, either a terrible misstep or the album centerpiece? All I know is, the track with Bryan Ferry is supposed to be the most decadent, derisive and contemptuous, especially with a song that originally seemed to treat its unfortunate protagonists with an either mawkish or mock-ish sheen. Instead, Ferry imbues it with an incredible pathos while Terje whirls slow-burn arpeggios around his voice that, rather than distracting, seem to allow space for the (actually, sincerely poignant) lyrics to resonate. Perhaps the link with the rest of the album is Terje’s ability to turn any genre upside-down until its dizziness turns to transcendence. Or, perhaps Terje is turning the very concept of kitsch on its head, realizing that the most ridiculous moments are often the most profound, that absurdity takes the most sweat and blood.

Joel Elliott

Lydia Loveless

Somewhere Else

(Bloodshot)

As a decorated Spotify “premium user,” I was recently invited by the music streaming company to have a gander at my “year in music.” Apparently I spent 19,576 minutes in 2014 streaming music, and listened to an inordinate amount of Umphrey’s McGee. And my number one most listened to song in 2014 was “Really Wanna See You” by Lydia Loveless. To which I say, you’re goddamn right it was. It’s the purest three and a half minutes of bar band rock and roll I’ve heard this year, and when coupled with a deliriously catchy ode to lust entitled “Wine Lips,” constitutes the front half of one of the strongest opening one-two punches on a rock record in 2014.

The 23-year-old Loveless records for Bloodshot Records; a 20-year-old Chicago label best known for blurring the lines between punk, country and rock and roll, in addition to having as bulletproof an artist roster as you’ll ever find. Lydia Loveless slots in effortlessly with this legacy, fronting a tough bar band akin to the late-‘70s iteration of the Heartbreakers, or Maria McKee’s Lone Justice. She gets the most press for her charmingly blunt lyrics that run the gamut from attempting to sabotage your ex’s marriage while in the throes of a coke binge (“Really Wanna See You”) or in her words, a “sad song about oral sex” (“Head”). But she’s equally adept at torch songs detailing the familiar country-rock trope about returning to your hometown and finding that nothing is the same (“Everything’s Gone”) and her taste in covers is impeccable (the late, great Kirsty MacColl’s “They Don’t Know).

And while her lyrics unquestionably make for good press, Somewhere Else succeeds simply because it’s a kick ass rock record from a gifted storyteller with a killer twang. Ten songs, forty minutes, and zero filler, not to mention a few tunes that deserve to be jukebox dive bar staples as ubiquitous as AC/DC. Plus, she refers to everyone living or dead as “honey,” which is charming.

David M. Goldstein

The New Pornographers

Brill Bruisers

(Matador)

I’ve spent an inordinate amount of time in my life apologizing for the last two New Pornographers albums. Challengers (2007) was always “a little sedate, but it grows on you!” Together (2010) was “better produced than Challengers and pretty catchy!” But it’s taken Brill Bruisers for me to finally realize what I suspected all along: Challengers and Together kind of sucked. I first heard the title track from Brill Bruisers on tinny laptop speakers six months ago, and my heart rate doubled and my pupils dilated like Jared Leto’s in Requiem for a Dream; THIS was the pure, uncut shit—the highest level of saturated, power-pop joy, that when they’re on, only A.C. Newman’s merry band is capable of achieving.

And the joy juices don’t abate; the underwhelming string sections of the past two albums are replaced once again by all manner of buzzy synths, and the result is easily the Pornos catchiest, most stridently upbeat effort since Twin Cinema (2005). A.C. Newman has stated in the press that Brill Bruisers was a purposely joyful album, stemming from a carefree portion of his life after a stretch of relative stress and unrest, and the whole thing feels like a rebirth; just look at that album cover! The vinyl even looks like a cross-section of funfetti cake! Even usually dour philosopher Dan Bejar gets swept up in the maelstrom, with “War on the East Coast” and “Born With a Sound” accounting for two of the hookiest, most uptempo tunes of his career. Hearing Brill Bruisers ultimately calls to mind the late Bill Graham’s off-quoted description of the Grateful Dead: the New Pornographers “aren’t the best at what they do, they’re the only ones at what they do.”

David M. Goldstein

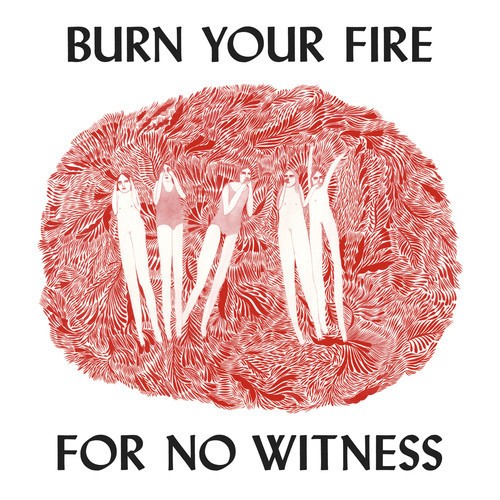

Angel Olsen

Burn Your Fire for No Witness

(Jagjaguwar)

The first time I listened to Angel Olsen’s record Burn Your Fire for No Witness, I was in the car, driving through east central Oklahoma. We had decided to take the long way home, and cruised a two-lane highway passing ranches, crumbling towns and countless humble churches, cars packing their parking lots but no people in sight. It was here, taking mental snapshots of Eggleston-ian Americana, that I first heard Olsen warble, then shout: “Are you lonely, too? / Are you lonely too? / High five! / So am I!” And it seemed to fit perfectly driving past townships of POP: 50, imagining small circles of people thrust together, gathering at church and building relationships upon a lack of options.

The characters, if you can call them that, that populate Burn Your Fire for No Witness all seem to be struggling with isolation in some way, either shut up tight in small rooms or standing alone in vast spaces, desperately seeking connections or running over mistakes in their minds. And Olsen’s music, likewise, feels distinctly self-contained sometimes, calling out for company other times. With warbling, slightly unsteady vocals, she repeats, in opener “Unfucktheworld,” “I am the only one now / You may not be around,” and croons softly in closer “Windows,” “Won’t you open a window sometime? / What’s so wrong with the light?”

To me, Burn Your Fire for No Witness recalls last year’s Bill Callahan record Dream River, another achingly lonely, Americana-tinged work that stays inside its own head for the duration, never leaving first or second person. Olsen, like Callahan, doesn’t create characters so much as emotions and dreamlike visuals, each evaporating elegantly like vapor trails. And instead of Callahan’s matter-of-fact delivery, Olsen’s Karen Dalton-esque voice places her strangely out of time, not old-fashioned sounding so much as mysterious: this is the kind of record that, found twenty years from now at a flea market and stripped of liner notes, will give someone the creeps in the best way.

Finally, then, Burn Your Fire for No Witness is an especially American record in the way it captures our culture’s tendency to isolation, in rural life as well as suburban. Angel Olsen has crafted eleven beautiful, often fragile songs that manage to feel both large-scale and small-scale, conjuring open and empty landscapes where people choose to shut themselves away, in their homes and minds, in ever-shrinking worlds walled with uncertainty.

Maura McAndrew

Sturgill Simpson

Metamodern Sounds in Country Music

(High Top Mountain)

What makes a country musician? It’s a topic that has come up a bit this year, usually in reference to a particular world-dominating pop star. But it’s a question also posed when discussing Sturgill Simpson, a Kentucky-bred singer-songwriter whose second album, Metamodern Sounds in Country Music, sounds at first like a proud descendant of the godfathers of outlaw country: Waylon, Willie, Merle and Johnny (plus patron saint Hank Williams). It’s an album that speaks of hard livin’ and being a hillbilly and simple country childhoods. But it’s also an album that explores the merits of psychedelic drugs; one that was inspired, according to Simpson, by Ralph Waldo Emerson and French philosopher Pierre Teilhard de Chardin; one that features a cover of a song by British new wave band When in Rome; one that has a song that plays backwards.

These strange pieces form the puzzle of Metamodern Sounds in Country Music, and by their sheer incongruity have prompted assorted hyperbole about Simpson as country music’s savior, and as the antidote to that sub-genre so derogatorily dubbed “bro-country.” But Simpson seems to see himself as nothing more than a songwriter and musician who doesn’t want to be boxed in. And he has fun with genre expectations, from the title, which takes them head-on, to the record’s opening, which can only be described as a hillbilly voiceover: “Introducin’ Metamodern Sounds in Country Muuusic.” Soon after, we launch into “Turtles All the Way Down,” the record’s single and a meditation on the possibilities of psychedelic drugs, with lines like “There’s a gateway in our mind that leads / Somewhere out there far beyond this plane / Where reptile aliens made of light / cut you open and pull out all your pain.”

It’s true that most of Metamodern Sounds in Country Music does stick pretty close to classic outlaw country, particularly highlights like “Life of Sin,” “Long White Line,” and “Just Let Go” (which begins with the memorable declaration, “Woke up today and tried to kill my ego”). But the album’s epic curveball “It Ain’t All Flowers” pretty well shatters that atmosphere in the best way possible. It’s part Odelay-era Beck, part ‘70s classic rock, and part “Revolution 9,” but what it is most entirely is Sturgill Simpson himself: a man who doesn’t want to “save” a genre but instead wants to see how far he can expand it, how much he can manipulate it, and how he can rearrange its parts to create something beautiful.

Maura McAndrew

Each Other

Being Elastic

(Lefse)

Allow me to quickly set up my favorite indie-rock record of this year—and really it wasn’t even close—via what will likely be my favorite of 2015. As Brent recently teased in his track review of “Pointless Experience,” which is from Viet Cong’s astonishing debut LP (due out next month, already burrowed deep in the communal CMG heart), one of the most promising bands of recent years, indie-rock or otherwise, is about to deliver big on their early material by completely abandoning it.

Viet Cong, in a pretty drastic shift in tone (sample lyric: “If we’re lucky we’ll all get old and die”), finds the band obsessing over a much darker, denser, This Heat-consumed sound than their Cassette EP just a year ago. Whether you think that’s a welcome change or not—and it is; trust us, it just is—consider Each Other’s Being Elastic the product of an alternate universe where Viet Cong’s voices suddenly jumped an octave and they went all-in with the most immediate, indie-rockiest aspects of Cassette instead. More of a focus on the joyous melodic twists of a song like “Oxygen Feed,” in other words, and less torching the whole goddamn thing/triumphantly rising from those ashes with a ten-minute post-rock behemoth called “Death.” More on that next month.

Being Elastic is definitely not Each Other’s own attempt to start over. I mean technically it is, in that it was written and recorded after initial sessions were trashed, but this is unmistakably the work of the same band behind Taking Trips (2011) and Heavily Spaced (2012). There is refinement in these twelve songs, the playing tighter and the production less cramped, but—and this isn’t meant as a criticism—fans of those EPs will know pretty much what to expect here: meticulous, incredible sounding guitars, ricocheting off each other in a constant jitter that falls somewhere between a coked-up Sleater-Kinney and Public Strain (2010); harmonized vocals, echoed just enough to be considered “dreamy,” sitting cozily in the mix; short-ish songs that are riddled with tangents and time changes, each wasting no time constructing the next hook. Also intact: their fondness for titles that sound like euphemisms for getting really stoned.

Each Other’s unrelentingly nervous energy can make this an off-putting listen, especially when you first begin to parse these forty minutes, but holy shit do they eventually win you over with those riffs. The instrumental payoffs alone, especially on songs like “You or Any Other Thing” and “High Noon in the Living Room,” would be worth every fidgety second that leads up to them if the melodies weren’t there to prop them up, but they’ve got us more than covered on all fronts. Being Elastic is loaded with fussily crafted and very catchy songs; even at their most plodding (see: the Fugazi-slowed-down-50% grumblings that make up the first half of “The Trick You Gave Up”), they manage to give us something to keep us hooked. So, for example, though after a few minutes of “The Trick” you’re probably ready to bail, they up the tempo what is probably only 2 but feels like 40 times, and suddenly bursts of distortion are howling over stuttering rhythm guitar. It’s glorious.

Though we’ll soon be heaping a lot of praise on another very talented Canadian band for doing the opposite, Each Other made a remarkable debut record by focusing on everything we loved so much about their formative EPs—clever, unpredictable songwriting, a serious ear for melody, and I can’t stress this enough: fucking beautiful guitar playing—and, graciously, thoughtfully, giving us more. Bless them; may they wait at least another few years before making their very own pitch-black ode to our inescapable, crushing mortality.

Scott Reid

Bleach Blonde Dudes

Prismo Beach Tape

(Self-released)

Bleach Blonde Dudes are four male humans who make and play music together in Portland, Oregon. I know these people personally, and so writing about their debut EP, Prismo Beach Tape, is a matter of finally accepting that all authority I must feign in order to leave the house each morning and tell the bus driver that I’m a music critic is, inevitably, a straw man I set up between the person I am who creates and the person I am who consumes.

Yet, like any saturated music scene, Portland’s is one of underrepresented genres (representative of totally underrepresented communities), incestuous collaboration, and shameless self-promotion, but also: insane talent, an unbridled DIY-ethos, and a regional chauvinism that actually adds value, distinguishing it from other new-music enclaves like Brooklyn or Austin, because Portland is viciously defensive of what it deems worthwhile in its community, which is often homegrown and home-nurtured apart from a national stage—this, in direct contrast to the aforementioned loci, which feel like black holes for nomadic bands seeking someone, anyone, to pay attention. Which to me means that the music I like is created by people I also like, and that if I wanted to erect illusory barriers in order to guarantee that my critical voice stay unclouded, I’d probably be a hermit. It also means that everyone kind of sounds like everyone else.

Except here are the Dudes, who sound more like themselves than anything, more like Everything at once instead of Everyone for a short period of time. In 2014 they finally self-recorded and self-released their debut, for free (except if you want to buy an actual cassette tape). The record went largely unnoticed, because these four male humans largely stayed away from drumming up notice, and while pieces of me genuinely wonder if loving these five songs should be chocked up to knowing the band so well—having experienced each of these songs, step-by-step, from conception to draft to performing to recording—I would much rather tell the story of my love for these five songs, however trivial, as an act of embracing the idea that such closeness, such intimacy, with any kind of music isn’t born, D’Angelo-ready, to be declared classic upon two or three listens, but stems from countless experiences, from interactions with people we love, watching people we love open themselves up to whatever it is that allows them to express veiled urges, or pain, or joy, or whatever.

Which is why this year Cokemachineglow is demonstrating our love in a way not just different from most sites of our kind, but different from every other year we’ve summarized: what began with removing numerical ratings, and then followed into truncating our list to 30 for 2013, has culminated in a simple celebration—a spirit party where we finally stop pretending that we’re some bastion of critical authority, and just admit that we’re a group of friends and/or colleagues who find communicating our experiences with art through writing is a deeply personal blood-letting, a method by which we can hopefully translate those experiences in ways that others can share in the same transcendent participation. Because what’s a piece of art if it’s never shared? What’s an opinion if no one ever hears it?

Only two of the Bleach Blonde Dudes are actually blonde, one being particularly ginger-y as opposed to Aryan-colored, which will prove in the ensuing years to be a social bane to his progeny, of which he recently had one, who, while adorable, is more translucent than not. There’s Jon Timm, lead singer and lanky fella who sits behind a keyboard; Phil Nelson, lead guitarist, aforementioned ginger, and the once-named most beautiful person in the band, or so said his wife, who offered this assessment reluctantly; Ethan Pierce, swarthy bassist, swarthier perfectionist, and the Dude who wrote the band’s eponymous song; and Bryan, drummer and consummate multi-instrumentalist, whose last name I didn’t really know until about six months or so ago, which makes sense given how Bryan has probably never said his last name out loud, potentially to anyone, in public, and also given how he emanates an aura of complete awe-inspiring aloofness. I think on Facebook Ethan’s tagged Bryan as “Handy Crab,” “Handi Crab,” and “handy crab.” I don’t know what any of this means.

At one BBD show earlier in 2014, for example, Bryan stripped to his underwear behind the drumkit, despite it being against most health laws and standards, and probably didn’t put pants back on until he woke up the next morning at home…or wherever it was he woke up. After playing their set, Bryan stalked into the street, still nominally clothed, to get some air and converse with showgoers. If anyone was discomfited by his nudity, no one dared say a thing to him; they just probably watched him disappear, skin touched by a thin shroud of dew as he ran off into the night.

“There goes Bryan,” they sigh together, leaning heads upon shoulders and clasping hands around forearms. “Goodnight, sweet angel.” Somewhere, miles in the distance, lost in the mist, a foghorn issues a long, forlorn bellow, much like a moose mourning its dead child.

“Wait, isn’t that his van right there?…Where does he even keep his keys?”

Bleach Blonde Dudes started with a song called “Bleach Blonde Dudes,” which was written by Ethan for 2012’s RPM Challenge, an annual event wherein musicians take the month of February to record a full album (10 songs) or 35 minutes of music. At the beginning of March that year, I volunteered to host a listening party at my house. As planned, we all sat around the stereo system in respectful silence to give each RPM project its due, accompanied, upon the creator’s choice, by a muted screening of whatever movie they wanted from my limited collection.

My Werner Herzog DVD collection was a popular choice; the first time any of us heard “Bleach Blonde Dudes” was in tandem with Fata Morgana, and people mostly argued about whether or not Herzog was actually filming mirages, and not the things the mirages were “reflecting,” which was pretty funny, because he was. Filming mirages that is. Not that Herzog doesn’t have a track record for manipulating the “reality” of his documentaries, but the whole point of the film was to meditate upon the surreality of mirages, and not whether or not they actually are mirages, so it was sort of like debating keeping fluoride out of Portland’s water supply solely on the basis of “that money going somewhere actually useful, like to art programs or hiring more teachers” or whatever, as if municipal funding is as easy to toss around as a frisbee in the parking lot of a Phish show, meaning that the debate isn’t about where the money should go, it’s about the fucking fluoride itself. Which, after a vote in 2013, didn’t go into Portland’s water supply anyway, so, anti-fluroide factions, since you raised something like $800,000 to keep fluoride out, in the ensuing year has that money gone toward hiring new teachers or buying some new paint brushes or anything that actually fucking matters? I hope that you’ve started to pay kids’ dental bills.

The time came for Jon Timm to play us what he’d come up with during February, and as is typical of Jon Timm’s whole life steez, he prepared a music video to go along with his 35-minute “Spirit Party,” a song that is now the centerpiece, in severely truncated form, of Prismo Beach Tape. The track is, like all of Bleach Blonde Dude’s music, an indie pop song hung from its Achilles tendon to bleed dry. It’s a grotesquerie at times, a still squirming earworm tacked to a dissection tray in a high school science lab, the internal parts labeled with little tropical drink umbrellas topping toothpicks. “Spirit Party”’s most notable organ is its heavy bass line, which gives form to its wandering sections—first Jon Timm’s creepy stanzas punctuated by fuzzy soundbytes probably from ‘80s horror films, then Phil’s complicated guitar solo forever unwinding, then more soundbytes and more bass and more of Jon Timm’s lyrics, unsettling, like they’ve been pilfered from a half-remembered version of Peter Pan spliced with the script to Beetlejuice. The songs that surround it on the tape, from “Serpent” to “Zebra,” from lovely harmonies to hellish noise, harpsichord arias to butt-rock salvos, are each carefully built edifices balanced on the head of those umbrella-topped toothpicks, radio-familiar pop ditties living moment by moment through sheer force of will. There is disaster at their fringes, danger in their bones; this is the stuff of awkward first dates that give way to transformative night terrors.

But, back in 2012, the music video for “Spirit Party” was an eviscerated collage of reused VHS splendor, meaning that Jon Timm probably found its source at “the bins,” tucked snugly into deep SE Portland, which is Goodwill’s elephants’ graveyard of odds and ends yet to find a home at one of their many outlets. I’ve never been to the bins, because I have deep-seated fears of sticking my hands into things that might give me hepatitis.

The visual accompaniment to “Spirit Party” began as a poorly shot karaoke performance of a pretty young woman in—if I remember correctly, which I probably don’t—a flight attendant’s outfit singing something that wasn’t “Spirit Party.” We guessed it was German, because its unsettling jambalaya of childish whimsy and Old World conservatism, dusted with a whisper of Grimm-like fancy, seemed like something the Germans would do.

That is, until the woman began to take off her shirt, and then her bra. Liberated from the strictures of underwear, she danced all the more vigorously. Jon Timm edited this into a series of pixelated and sea-sick loops—her shirt comes off, then her bra, her breasts swing free, she raises her arms to sing the chorus, she jumps, and then she turns and her clothes return to her so she can remove them once more—developing motifs to support and represent sections of his rather long song suite. Nervous laughs covered up uncomfortable shifting. Everyone in the room hoped it would go no further.

It did. A young man enters the frame and feigns interest in singing with the young woman, though we knew instantly what he was there to do. People began to ask Jon Timm what was going to happen next, which was a veiled way of asking, “Are we actually going to watch this?”

Yes, we are, and we did. The young woman spends a large portion of the Party blowing the young man, and really: that guy looked too young to be doing what he was doing. But those are Germans for you.

It’s hard (heh) to describe the tenor in the room. No one got up and stormed out, sensibilities offended—not that anyone should have, because it was, if anything, a really funny thing Jon Timm was doing—but no one questioned Jon Timm as to why he was doing what he was doing. And even Jon Timm didn’t seem to totally make the connection between what he had created and what the effect would be on a group of people focused solely on the TV, together, in the dark.

It wasn’t a traumatizing experience or anything, watching Jon Timm’s cool-ass weirdo porn-thing with ten other friends in the dark while no one said a word, and it was somewhat endearing, really, that Jon Timm never asked us if we even wanted to watch this thing, mostly because that kind of willing disconnect—between shock and shame, between value and obscenity and controversy—is so rarely experienced, really only glimpsed in the occasional fearlessness of a Jon Timm, or in the sweaty underwear of a Handy Crab as his butt disappears over the next hill.

Yet: not everyone will want to watch whatever it was Jon Timm was doing. Some people may find it offensive…and if not offensive, then maybe just uncomfortable. I hope that wasn’t the case. The sad byproduct of being an artist—someone who creates something that resonates with people in ways they have yet to experience—is that one must sublimate all the self-sustaining urges one experiences when confronted by uncomfortableness. In other words, if you feel really fucking awkward when watching porn with your friends, then you probably shouldn’t watch porn with your friends. Perhaps your body is conveying to you the direness of your actions: here is an event that shouldn’t belong in your head.

Not that it shouldn’t exist, or that Jon Timm shouldn’t have followed his muse down the rabbit hole; I have the same feelings about Pier Paolo Pasolini’s Salo, which to this day I still question as something I should have watched. I respect the film in and of itself, and I admire Pasolini as an artist with guts, but: should those things be in my head? They’ll always be there. I see them now: a naked pubescent, scooping shit off the floor, bringing it to her mouth.

In Portland, where the Bleach Blonde Dudes live, the music scene, and by extension the art scene, is one of talented folks avoiding being seen as prudes. Everyone is game for everything; this is the modus operandi of a young, progressive, artistic community. And not because of the value of the thing itself, but because of how that game-ness looks when paired with that thing. Take Ron Jeremy’s Club Sesso. Maybe you feel really, really uncomfortable being naked in front of other people, let alone having sex in front of other people, let alone with lots of other people. It’s not a moral judgment; it’s just your body telling you something important. It doesn’t make you a prude, but unless you go around explaining to everyone that you’re not, the intentions and the deeds (or the refraining from that deed) get all lumped together.

Sometimes I ask myself if the Bleach Blonde Dudes will ever be popular in Portland. They’re more than talented enough, more talented, in fact, and technically adept than most popular musicians I know here. But they do nothing to de-prude themselves: they make the best music they can together, and they enjoy that process. They have fun playing; they take chances. Ethan sometimes screams at Phil mid-song: “You’re doing really good!” Which is such an un-cool thing to yell at someone. There’s no mystery to them, no posturing, no networking beyond whom they happen to know. Which is why I feel so beholden to spreading the word about this music, this EP, this passed-over gem amidst a simultaneously loving and indifferent scene. There is that existential disconnect in the very DNA of their band, that networking and the rigmarole of Portland promotion makes them uncomfortable, and so they don’t do it, and they maybe don’t really see why they should. Because then they’d feel uncomfortable. So others have to, others who imbibe shame as a necessary evil, who endure hype as the only mechanism by which hobbies become careers, by which passion paves way to pay. I accept that this is who I am. But that doesn’t mean I can’t be more than that.

Dom Sinacola

Chad VanGaalen

Shrink Dust

(Sub Pop/Flemish Eye)

I have, along with many Cokemachineglow writers in the past 12 or so years we’ve been a thing that you can visit on the Internet, written extensively about Chad VanGaalen. In fact, I remember specifically that Infiniheart (2004), long before CVG signed to Sub Pop, was one of the first albums that required my attention when I walked into work back in 2004; Scott didn’t so much force my ear as position the album within an undeniable purview, sort of like: this is more than what we like at CMG, this is what we live for. Thousands upon thousands of words; a practically guaranteed spot on any CMG year-end; celebration of a music video I watched so many times I even had to show it to my mom, who was shocked at what I spent time subjecting my brain mush to; the acknowledgement from other notable websites that we are notable mostly for our laser-beam-focused affection; potentially one of the first interviews he ever allowed; and even a tee-shirt design Chad made specially for us so that we had a uniform to wear to the Pitchfork Music Festival that one time—this, all of this, is only the detritus of devotion, each a shred of shrapnel flung with volatility from the core of whom we are as a website of music critics, each piece one more attempt to get ever closer to building a full monument to, a suitable altar for, a whole picture of that true love. When we talk about Chad VanGaalen what more can we say?

Because: big fucking whoop. Cokemachineglow really liked the new Chad VanGaalen album. And Shrink Dust, the man’s fifth album (not counting his Black Mold project, for no other reason than organizational, because it is absolutely representative of CVG’s well-established sonic personality; and not counting the first Women album, which both informed where he would go production-wise from that point on and was informed by his work ethic) is as good as anything he’s ever done, though perhaps less of a slight aesthetic surprise than Diaper Island’s lo-fi shift from Soft Airplane’s glistening grossness. This hardly matters: Shrink Dust, a supposed soundtrack to VanGaalen’s in-the-works sci-fi film (or something; the guy’s always got so much going on it’s hard to figure out where one project ends and another begins), is itself a culmination of everything that makes Chad VanGaalen so worthy of our unbridled infatuation.

Disturbing but oddly affectionate cartoons cordon off inner-worlds from other; feedback and cosmic fuzz eat at the corner of consciousness; instruments that are not instruments found their origins here, and they became more than instruments; there is a song named after a human female whom Chad probably loves, and it is a straight dose of pleading gorgeousness—pleading not to the titular person, but instead to a higher power: tell me, tell us, where talent comes from, why talent is, what talent must do. There is no answer, there is only all of these attributes on brighter display than they’ve ever been before; there is no real question, there is only the promise of another Chad VanGaalen album to come, and the safe, warm reassurance that it will be magnificent.

Dom Sinacola

Zola Jesus

Taiga

(Mute)

At some point in 2014, I fell in love with Zola Jesus. Actually, like any slowly simmering affair, though from that point all time and geography lost its hold, I remember when and where it began: in a cubicle, in earbuds, adjacent to countless empty cubicles, in an office too big for the staff inhabiting it, enjoying a climate too well-controlled for the amount of people complaining about it—stop me if this sounds sad, because I don’t mean it to; if anything, this is a paean to office life, a denouncement of studio space—at a point in my life when finally, somehow, contentment didn’t seem an unobtainable, emerald-green, unmown horizon. This was recently. Sans struggle, for once I had room for a voice like Nika Danilova’s, and so I acrobatically overcame all prejudice—that on Sacred Bones she too readily bore the signifiers of witchhouse, whatever that meant based on whatever thinly understood semiology I was accessing; that in promo pictures she motionlessly writhed behind gauzy veils like every moment of her life was in mourning—and for no reasons other than the luxury of whimsy, and the welcome lack of obligation, I listened to last year’s Versions. By “Fall Back,” I was smitten.

I’m not sure what I was expecting—difficulty, probably, which is shameful in itself, that somehow I’d be stymied by an artist committed to challenges before even attempting to understand what was so challenging, as if the symbols attached to her were her own doing, profligate for the purpose of posturing in order to make her difficult sound a selling point, as if she was all: Greetings, human. Prepare yourself, for I am like nothing you’ve ever heard.

Except, she is. The grand mystery of Zola Jesus is that there is no mystery whatsoever. And so in this one record, her fifth (more impressive given that she’s only 25), she paints 11 different approaches to pop stardom, each a crazy attractive tact on what it means to be a vocalist in a world unable to accept that there isn’t also something more to a record that arranges radio-ready electro-ballads like chamber pop standards. And perhaps more than any other vocalist this year, Danilova’s music is utterly subservient to a voice that carries everything—melody, texture, drama, unspeakable dynamism, a subcutaneous seduction to lean in—a voice that feels equally untrained as it does capable of anything, powerful and inflatable, totally, seamlessly expansive unto whatever dimensions you desire. Even when songs such as intro “Taiga” or bass-splattered “Dust” or playfully horn-y “Hunger” succumb to drops to which the likes of Skrillex would nod, absolutely in thrall, his stupid hair bobbing stupidly, Danilova’s voice gathers each song’s energy ravenously, emerging from dark corners electromagnetically—the bridge to “Hunger,” especially, is astounding, both in its sheer beauty and its restraint—pulsing, swelling, like the life-force of the sounds around her are actively imbibed, inhaled, made one with Zola Jesus’s punishing breadth as a songwriter. There is little doubt that when she heatedly insists, “And I say no one can stop me now” (“Go [Blank Sea]”), she is speaking from experience. Witness how she reuses that same trumpet-ish tone for “Hollow” and then again for “It’s Not Over” (not so demurely the album’s final track); she will do so as liberally as she wants to. She is retelling the same story, and telling us that she is doing so. Not because she has run out of ideas, but because she understands her own narrative as a musician is one of building, rebuilding, and refining, the point from which she began always clearly in view.

Zola Jesus called this record Taiga, an appropriate reference to the fact that this may be the fullest, most fertile LP she’s ever written, but more telling is that, alluding to the dense forests in which she grew up in Wisconsin, as an artist she’s come full circle. Maybe in my relative amateurishness as a Zola Jesus fan, I’m more than surprised than most that this record wasn’t as well-received as her others have been in the past, but in carefully inhaling her oeuvre in much the same way she inhabits her rather uncomplicated synth-and-string arrangements, I see little difference from past efforts. Here she vacillates between songs of devotion and songs of unrequited love; here she skirts the bounds of electronic music by injecting a barely perceivable tactility to everything she touches; here she seems a confident singer who will only become moreso.

And so it’s coincidental that in the same breath I discovered Versions I was discovering Zola Jesus, in total—2014 providing me with the opportunity to celebrate her music with one more album that, in no substantial way, is any more or any less indicative of her exquisite talent. Maybe it was love at first listen, reveling in symbiosis as its basest, knowing that though you don’t know someone you still, in some deep-seated place, understand that person. Or maybe I’ve been given a gift: I have the benefit of newness in encountering all that she is; I have seen the forest for the trees, and I feel at home.

Dom Sinacola

Kinky

Kinky

(Self-released)

I spent a lot of time this year listening to Kinky’s debut in places where there are no gut-punches, only quiet sighs. Waiting to get the train, I’d listen to these seven songs; walking to work, it’d be this record on my headphones, centred against the commuters hovering in my peripheral vision. It’s fitting: Kinky is the punk rock equivalent of an unrecognised dead stare, a fight against those who shrug off pain in order to get where they’re going—those who make ignorance their lifestyle in favour of someone else’s livelihood. These fuck yous might never be heard by the people they so desperately need to change, because they come from an underground scene those people have either never heard of, or would else live to shut down. They sound amazing there, but I’d like to hear Kinky’s screams of “Enough of your fucking sexist shit! / Recognise your privilege you fucking prick!” played in place of train announcements.

The details, though: Kinky are a no frills three-piece from Durham’s thriving folk-punk scene, which deserves none of your eye-rolling and a lot of your time. One of the most politically forthright and compassionate scenes to appear in England, it’s done a lot of good calling out things such as bullshit immigration laws while promoting a lot of queer love. Kinky, though, is fire: it’s a record that looks outward at the dicks in and out of the scene, be they misogynists, transphobes, neo-Nazis, or clueless bros. These simple songs are amped up and cut down to size, fashioned at hardcore’s revolving door pace–a striking sample, a quick song and an unmoveable chorus–but with enough clarity to hit their targets. It might be one of the simplest albums I’ve heard this year, but its duality is incredible: it belongs to the punx and could knock out an EDL member at the same time. It was made for both sets of ears.

These songs are barbed-wire: try climbing them and you’ll be thrown to the ground. They suggest that a gang vocal in the minority–in this case, three people max–can wreck the indifference and ignorance that lives in the majority. Between the distorted chords, thick bass and sick as shit drums, I have a slither of hope for a world where the pricks of these songs listen up, where the safe spaces intruded in on “F U Str8 Boi” can be respected and expanded. For now, at least there’s “Bro Destroyers,” a theme tune for a sitcom with an episode where the LAD Bible gets thrown into the back of a book burning van.