Features | Lists

By The Staff

Art: Nick Howard, Formation / Luis Rivera

Music criticism is predicated on a set of impossible promises. It says, we listen for you; we feel for you; we judge for you. By what authority do we critics serve as representatives for the affective squadrons of the virtual domain? Is it our specialized knowledge? Most don’t have any. Is it our florid, fluid, fluent prose stylings? We take these sounds and turn them into words—a process every bit as mysterious and quixotic as medieval alchemy, only the gold we seek here is: meaning. To cover over the generally accepted axiom that the effect of music is a subjective matter, we accumulate opinions when the year gets old and elect a canon for posterity. We somehow forget that objectivity is more than just the difference between subjectivity and intersubjectivity. We revel in the decayed residue of emotions we could have kept safer had they stayed closer to us. And how the lists proliferate.

Over the last few years, we at Cokemachineglow have gradually taken steps away from the reduction of aesthetics to demographics. This feature is our attempt to complete this process. You will find no rankings below, no hierarchies to stack up against the rest. Nothing but articulated affirmation with a healthy dose of enthusiasm. It is born of the conviction that music moves us in a primal, elemental, essential way, but it moves us all so differently and on so many different levels that we are both united and divided by it. To pretend that there is more to the evaluation of music than this diversity of opinion—to believe we can pan or praise a record and be right about it—is to endorse the noxious parasitism whereby critics build their careers at the expense of the very artists who make those careers possible. Out of respect for these artists and their art, we wish to shed such pretence.

Below, you will find two groupings of records. The Unison list contains 10 records which represent those singular points where the tastes of our staff converged the most. The Harmony list that follows allows our writers to individually open up about the albums that meant the most to them this year.

How you approach these categories, dear reader, is up to you. If you tend to identify with one writer’s taste more than the rest, head for Harmony and then our Staff Lists at the end. If the number of CMG writers whose names end with “A” is simply too overwhelming for you, then hold fast to Unison. If, after all that, you’re curious about more records that our staff agreed on but didn’t have time to write about, we’ve got an Addendum on page 5. Don’t care for any of that shit but wouldn’t mind a Spotify playlist with all of these artists? Corey’s got ya. Either way, we hope you find something here to make this increasingly dark world a little brighter for awhile.

Unless you’re into Swans, in which case you probably like the darkness. That’s cool too.

******

Shabazz Palaces

Lese Majesty

(Sub Pop)

Lese Majesty is one long thought. It’s a singular exclamation in a wiser ancient tongue, a pure hue refracted through the prism of the English language into 18 different shades. What it communicates, and the way it communicates, is new; it eschews the “comfort of the uninventive.” It will dismantle your expectations of what a hip-hop album should be and polish the pieces to a fine obsidian veneer before reconstructing them in a baroque monument to discontinuous epiphany. And then feed you cake.

Everything here fits together. But there’s no blueprint; the rules are created by Shabazz Palaces as they go along, and you’re in on the game. Unlike Black Up (2011), which stared you down as it slapped you awake, this record does feel like something to be, strictly speaking, played. Even to write about it here feels wrong; these songs aren’t documents but “languages for dancing.” Lese Majesty represents the best kind of experimental music, where the joy of the experiment is the most palpable thing. There is a song called “Mind Glitch Keytar TM Theme,” and it rules.

Black Up was brilliant, but a bit too cold for me: I felt locked out rather than locking into those beats, uniformly commanding though they were. Here the tones are warmer, more welcoming, and once those chords start chording in “Forerunner Foray” I find myself sinking into some kind of trance that doesn’t break its hold even after “Sonic MythMap for the Trip Back” deposits me on the other side of the solar system. So gorgeous and intricate is the music here that it runs the risk of obscuring Ishmael Butler’s lyricism, which would be a shame since Butler is among the deepest and most eloquent emcees working today. If you need evidence of this, look no further than opener “Dawn in Luxor,” where Butler’s language dances across the strictures of grammar and sense to ensure its creator a place among “modern cubists or surrealists.” That the music bears out this content in its form ensures the success of Butler’s high-art ambitions: the result is no less a party. Here, “sounds pour like golden licks of time.” Make some for them.

Brent Ables

FKA twigs

LP1

(Young Turks)

On LP1, Tahliah Barnett leaves no vanishing point. Every ebb and waver of every pitch-bent chord is meant to defy perspective; parallel lines stay parallel no matter how far you look. Barnett provides picture, structure, and diction, but emphasizes that these things don’t always matter. For example, you can hear words on “Closer,” but you can also hear not-words; the song is a duet where one voice is a synthetic harmony that has had its attack removed. When mouths stay open? Consonants become vowels and words become round tunnels. Noises become the skeletal structures that keep these tunnels from closing or ending. On multiple songs, words are stuttered and repeated in the foreground or background; things said out loud conceal, reveal, or transcend things that are too hard to say out loud. Non-vocal noises are given vowel shapes; clauses have no punctuation. Text and subtext are given equal volume; stray thoughts are captured and become part of the fabric of the music. Thoughts are abandoned or interrupted. Communication breaks down. LP1 is almost the same conversation 10 times in a row, rendered in exhausting detail.

Barnett isn’t doing stream of consciousness; the structure here is stasis. Viewed up close—and each song here is really close—these iterations of this conversation seem laborious and epic. Barnett plays a different version of her omnipresent “I” in each version. Some “I”-voices are bold, some are reticent, and some introspective. If we zoom out, however, each “I” is identical—i.e. the same person—and each song becomes part of a greater structure: a woven tapestry from which all the horizontal threads has been removed, or a series of identical tunnels running in parallel. Rigid. Strict enough to keep bodies from engaging in motion, or pleasure. Stranded, caught over-thinking single, fraught words that never reach their conclusion. Even “Hours”—the only song on LP1 that literally describes two bodies actively touching, and not just talking about or thinking about touching—is about being caught in a moment: kissing for hours. Except…all of the lyrics are about the processes and theory of kissing. Barnett takes pleasure in hours of the epistemology of kissing. Which is awesome and sad. The image she creates is two mouths making shapes, joining to make circular vowels larger. It’s mouths open, breathing in and out at the same time.

This is why every song on LP1 has a “you” and an “I” (on “Video Girl,” the “I” is Barnett and the “you” is everybody else); the album is entirely about the difficulty of two entities connecting, and how the relationship between two entities affects the way each entity sees itself. People yearn for one another; people stay lonely. On “Two Weeks,” Barnett tells a potential lover that they must be the sole instigator of an affair; she won’t betray a ciphered third party called “her.” Barnett’s “I” in this context notes that they can “fuck you better than her” at the same time that this “I” cares deeply about the narrative surrounding this liaison: this “I” will take pleasure, but not the guilt of providing a starting point. The result? The “you” of “Two Weeks” is literally caught between the “I”’s legs, mouth open, forming a vowel. Those legs? Two lines extending into infinity. That mouth? If the “you” breathes in, what’s between the “I”‘s two legs will make the “you” “higher than a motherfucker.” If the “you” breathes out, it’s probably just to say, “no,” but doing so while staring down infinity. There’s an epic choice here. At the same time, for all the implied sexuality here, emphasized by the melodic way “high” is sung, note that the chorus makes it clear that it will take two whole weeks for the “you” to no longer recognize the “her.” There’s no instant magic here; there’s just iteration: “‘I’ can make ‘you’ forget about ‘her’ if we have a lot of sex over a two week period.” Just like how on “Hours” intimacy slowly “rounds off your edges.” Or how on “Number” the “I” asks, “Was I just a number to you?” An iteration? Or how also on “Number” the “I” asks, “Was I just a?” before the clip stops, as if what the “I” could be has infinite iterations.

Obviously it could. Whether looking at the cover or listening to the music, numerous versions of the “I” emerge. Is the “I” bruised and in pain? Are they sad and lonely? Are they blushing and innocent, or blushing and fulfilled with pleasure? Empty with pleasure? Perplexed with pleasure? Are they object or subject? Protagonist or antagonist? This confusion seems to me to be the point. This album is not about ennui or existentialism; it’s about the way every exhalation, gesture, and word is loaded with so much meaning that the meanings themselves become structures that hold us in place. Real conversations can’t end because context keeps people from expressing themselves. Ideas are repeated. Narratives are repeated. Longings are repeated. Sexuality isn’t just about desire; it’s about how we identify ourselves. Every song on LP1 has a “you” and “I” because every “you” and every “I” is a person trying to be. Barnett explores being different “I“s even though the result is often the same. On “Two Weeks” she plays seductress. On “Hours” she plays loving and intimate. On “Number” she plays hurt and confused. On “Pendulum”—the only song on the album where the title is neither utilitarian (“Preface”) or said in the song, and therefore the only title of a song on the album that is purely descriptive—she plays unable to express her feelings. She—at the halfway point of her album—is a pendulum between iterations. This could be read as a feminist deconstruction of the roles women are expected to play in a patriarchal society; this could be read as a narrative exploration of the same roles. Either way, these are sexual identities that have complicated ideas about sex.

I don’t know that there are really conclusions to make here. I think what FKA twigs is trying to pull off is a work in progress. But “Kicks,” the song that closes LP1, is about self-pleasure, and its final line is this: “Baby, it’s clear.” It’s hard not to read that as the sole emphatic expression of closure on an album that is otherwise about everything but.

Mark Abraham

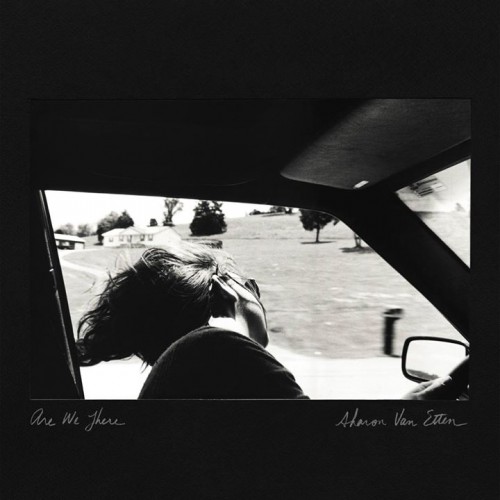

Sharon Van Etten

Are We There

(Jagjaguwar)

Sharon Van Etten’s is a sadness both entirely personal and universally understood. You can become enfolded in it, luxuriate in it, repeat it on a loop the way a trauma victim relives an accident. It’s ocean deep. Romance is a blasted countryside, a haunted room, something in your peripheral vision that you look for too late and it’s gone. Can there be any praise greater than that she’s a songwriter who makes us feel it, even through the deluge?

Where her early efforts were stripped down affairs, and her last album, Tramp (2012), seemed somewhat at odds with the more meticulous aspects of its production, Are We There is the promise of a fully-formed Sharon Van Etten album made manifest. Here, Van Etten is assured, even comfortable in the nooks and crannies of her songwriting. It’s perhaps no surprise, then, to learn that she also produced the album herself. “Taking Chances” is her best song, and epic mantras “Afraid of Nothing” and “Your Love is Killing Me” would be right up there if her whole catalogue weren’t turning out to be so damned consistent.

It’s not just the Glow in love with (and alienated by) love itself. Are We There was one of the most critically acclaimed albums of the year, recognized by critics with differently tuned ears and strategic agendas as something authentic sounding enough to bypass both. It sounds so natural that you might be surprised to see how many performers were involved—seventeen in all, building around Van Etten’s undeniable voice. And, my god, that voice. It’s got to be one of the most distinctive and instantly accessible voices on the indie landscape today, a sultrier counterpart to Neko Case’s crackling jibe. Van Etten’s vulnerability emerges from a tired drawl, a world-weariness that is at once Zen and urgency distilled. It’s less mournful, maybe, than desirous.

When I listen to Van Etten’s voice, and her lyrics, which so often play on the notion of someone doing something that they know might not be the best for them, what I think of is a person saying “I want this so badly I can’t help myself.” Van Etten’s achingly human music is unafraid to wallow and reel in that want. It’s honest work, and its honesty is at the very heart of what makes it so excellent.

Conrad Amenta

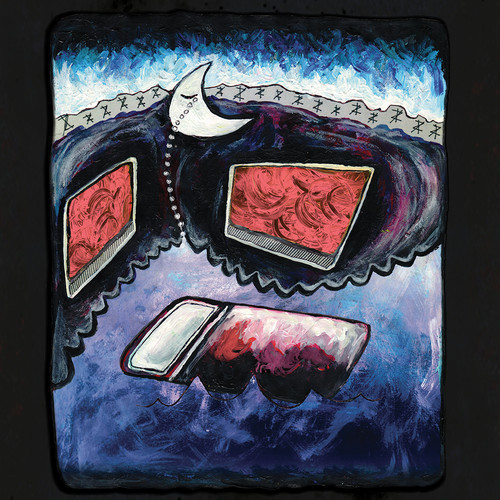

Hundred Waters

The Moon Rang Like a Bell

(OWSLA)

Ugly music is easier to explain. That’s not to say it’s less artful, less complex, that it holds less potential to pull you toward the transcendent (for further reading, see the Swans entry below)—just that music designed to rip, to tear and shred, to pummel and bludgeon, feels more wholly of our world. Maybe it’s the countless liters of blood represented in any given issue of a respectable newspaper these days, or the gnawing sense of disconnection that grows fatter every year even as we’re increasingly never alone and never still or silent for a moment, or just the endless parade of human misery on display during a typical morning commute in New York City. Yeah, we say amidst all of that darkness, I understand Swans, or Pharmakon, or Xiu Xiu. That’s me, too. That’s us.

In that context, The Moon Rang Like a Bell shocks more than anything reverberating from the filth-caked walls of a Bushwick noise venue. Where does this music come from? How do four people, against all odds, create sounds at once so beautiful and so irrepressibly human? How, in this world, do we deserve the moment in “Murmurs” where Nicole Miglis, stuck in a manic, obsessed loop of “I wish you / I wish you / I wish you…,” finds the composure to break free and admit her desire—“I wish you…would see what I see”—as the song’s tidal percussion flows beneath her in the thaw? Or, how after that tiny miracle, we’re battered—it’s not the right word, but we’re still easing ourselves away from the language of violence—by another, as Miglis soars to a crystalline high, kneading the ache out of every syllable in “when I called you / Were you there, were you there, were you ever / Alive?”

Plenty of listeners will likely dismiss The Moon Rang Like a Bell as “easy listening” or, worse, “NPR music.” And fair enough: it is easy to listen to this record, and people who think Sufjan Stevens is more “national treasure” than “wet egg noodle” will also find much to enjoy here. But think of it like this: if your foot—and I don’t mean to assume anything about your podiatric health, but bear with me—is ensconced in an exoskeleton of callused skin thick enough to make a beetle stop when passing you on the street to tip its little insect hat in respect, you won’t enjoy a foot rub very much, will you? You won’t feel a thing. But then if you scrape the dead skin away, you’ll be left with something soft and sensitive, ready for a toe-arching rub from lover or a mirthless older woman in the back room of a fluorescent-lit massage parlor. Here, The Moon Rang Like a Bell is that lover, pressing life back into your sore, overtaxed muscles and your chapped, weather-pocked flesh with its patient and knowing hands. It is also the pumice stone or the dozens of tiny fish peeling away your calluses, reacquainting you with the world of warm touch and unguarded, unflinching feeling. Give it time. Let it do its work. Don’t be afraid to be at a loss when you try to explain how it changes you, incrementally, layer by layer.

Corey Beasley

Run the Jewels

Run the Jewels 2

(Mass Appeal)

Corey: You know, Kaylen, I’m not one to talk—I’ve never had any friends—but one group this year gave me hope for the possibility of finding real, platonic friendship in this crazy workaday world: Run the Jewels. Killer Mike and El-P, two dudes who never got enough love on their own, found each other, found success, and found a friendship for the ages.

Kaylen: It’s beautiful. It’s the Fox and the Hound, chewing-on-each-other’s-ears-and-or-sticking-it-to-the-cops friendship album I’ve always looked for in rap albums. Chokes me up. And I don’t normally even like rap that tries to teach me about the world.

C: Right. In that spirit, I thought you and I could talk about our favorite songs on Run the Jewels 2 and riff on some Friendship Activities those tracks make us want to do. Let’s rap.

K: Are you sitting backward in your chair with your arms crossed like a Cool Teacher?

C: Hat’s on backward, too!

K: SAME.

Lies, I don’t have a hat.

Can I borrow your hat.

C: No. So I’ll start with “Jeopardy.” Mike’s ad-lipped introductory speech leaves me braced for impact, ready for El-P’s All-Percussive-Everything beats to blow me out of my sick kicks, but El’s a sly dude—compared with the opener of last year’s Run the Jewels, rather that record’s subwoofer-slaying title track, “Jeopardy” oozes insidiously. So, in that vein, when I hear “Jeopardy,” I want to take my best friend to IHOP for a pumpkin pancake breakfast on a calm Sunday morning before church—but then, right when our Pancake Ambassador bends over to squirt whipped cream on my ‘cakes, I grab his hair and fill his face holes with blueberry syrup while my friend tells the cashier to hit us with that hashbrown cash or this pimple-faced batter-monkey’s losing his turkey sausage. Surprise! Then we feast gratis at Waffle House. Smothered ‘n’ covered, bitch.

How about you!

K: Oh see I’m laying off the sizzurp for minidress season. But my favorite is “Lie, Cheat, Steal.” It’s so puffed up for each other in the best possible—and also Lord of the Rings—kind of way. The way Killer Mike’s all, “I’m fly as a Pegasus” and El-P is all “Blow from the nose I’m a dragon to a gnome.” Then he says “milieu” like a boss. It’s like this Youtube video I saw of these dudes basically doing their best moves to Pretty Ricky’s “Late Night Special,” taking turns humping an ottoman, in front of a mirror…there’s even this bro walking around just like grinding on the walls.

C: That is so sweet. Name the ottoman and I’ll meet y’all there. Here is a selection of nihilistic fire from “Blockbuster Night Part 1”: “You rappers doodoo / Baby shit, basic booboo”; “It’s all a joke between mom contractions and coffin fittings”; “No hocus pocus, you simple suckers been served a notice / Top o’ the morning, my fist to your face is fucking Folgers”; El-P’s entire second verse. Before Run the Jewels 2, when I caught a glimpse at the gaping maw of meaningless sucking at our pathetic self-penned narratives, I might just get blazed and watch The Mindy Project, or read Baudelaire in a French accent until my roommate hit me in the head with a hammer. But now, Mike and Jaime have taught me to embrace the inherent comedy within this little farce called life, and I’ve never been happier. This song calls for skipping hand-in-hand with your friend down the middle of the West Side Highway during rush hour, spinkicking a cop and laughing while he knocks your teeth out with impunity.

K: “Close Your Eyes (And Count to Fuck)” is straight up like my friend Christina walking into my apartment (because she has a key) and I’m practicing booty-popping in the mirror. I don’t even bother to stop. She’s just like. “Oh hi, that’s coming along. That’s not nothing. By the way when do you want to get it together and kill some cops?” And I’m like still booty-popping but now it’s like the hate-fucking the floor when I drop it and I’m like, “Oh right. I’m super angry about all that and completely agree. We really let ourselves slip in the cop killing department.”

C: “Close Your Eyes (And Count to Fuck)” makes me want to fight an entire district of police officers and prison wardens, armed with only The Chomsky Reader in hardcover for busting noses. It would look a lot like this.

I understand my experience might not precisely mirror Tony Jaa’s, but I’ve already cracked my knuckles and there’s no going back.

K: I’ll bring my People’s History…, you grab that Chomsky. We will hit some cop bitches with truth. And also really actually heavy books.

C: Yeah those will leave a mark. Do dudes need sidekicks for Run the Jewels 3? “3” is right there in the title.

K: Dream big. Be a fucking Pegasus. Can I borrow your hat though.

C: Still no.

Corey Beasley & Kaylen Hann

Boogie

Thirst 48 Mixtape

(Self-released)

Long Beach rapper Boogie’s Thirst 48 is a tape with casual depth, sanguinity, a lurid landscape of pristine beats, rhymes that rotate on an axis of a product of his culture lampooning that culture as he owns it as he owns his heart as he “hates that shit,” and best believe he‘s not thirsty but he’s sipping. It’s also concise, dodging grandiosity and grandstanding; there’s a track where Boogie just, basically and gloriously, talks about being a “Westside nigga.” It is so plain, what Boogie does here, so effortless. “Who can do it like you? / Who can do it like me? / Who can do it like we?” We can do it like we, but who can do it like Boogie? And who can do it like us, asks Boogie. Then, how he expounds on “Do It Like We,” a fractal choir pin-wheeling gleam and shade around Boogie’s chill, numb, impassioned lilt: “It feel different when you real with it / We never change, but we feel different.” Uh, yeah, I feel different. Right now.

The sacrament of Thirst 48 is that it includes us in something too right and good for us to be included in. Anyone could have made this record until Boogie raps in such a way as to remind you, no, you couldn’t have. These beats aren’t that special except for their clarity, their cool warmth, coastal dusk at their core, city lights glinting off their edges, part of an environment that we are not part of, part of a vision that we don’t have until we hear this record. This is cloud rap with the clouds parting, divine favor beaming upon Boogie’s head, anointed. So Boogie raps, and it has the taste and color of pure truth. It’s the best non-Tribe Q-Tip record. It’s the best dream Wiz Khalifa and Curren$y could dream, slipping from their memory’s grasp as they crawl from out their fog; they scramble to jot shit down, pick up a pen but it’s a blunt, recede into blankets, sheets, ashes, the unbearable lightness of being a rapper. Thirst 48 is the splitting crack in the earth that swallows Lil B whole. It’s the real Kendrick Lamar. On the slow bounce of jam-and-a-half “Bitter Raps” Boogie eviscerates social media and urban culture plus the refrain that he’s not on the same thing until, in the last verse, “I’m probably on the same thing.” Danny Brown uses the confessional aspects of rap to find the beauty in real ugliness. Kanye dresses it up in the theater and self-loathing pomp of his ego. Meanwhile, Boogie seeks confrontation, conversation, and absolution.

“Won’t you save me?”, Boogie asks on the soaring glide and dip of the opener. That’s flipped on the penultimate track “Save You,” Boogie offering to save “you.” Us. “We fuck to Confessions (confessions).” On the opener Boogie observes that his/our generation lacks love; on “Save You” he claims “we’re made for love.” Boogie bemoans, in general, “Black Males” and then in the last few bars it’s lamentation as beatitude: “Free my niggas / We got problems we can’t pinpoint / I pen-point you straight to the pen that points get you in / Wind push me straight to the Point / What’s my point, my niggas? / Pen down / Writing to this pen pal / Really ain’t no point to that shit / Smoke a joint to that shit / Yeah, we yellin’ but we silent / Ain’t no words for that shit.” And I’m dumbstruck.

The song ends as Thirst 48 goes on, but then the record, too, is over too soon…but it is never over because I never stop playing it, I never stop hearing it, thirsty for it. Boogie decries the thirst for the ephemeral as he recognizes it, as it stews in his gut, as he molds it into a vessel for the eternal. On “Still Be Homies” he limns the material ambitions and transactional relationships of “being homies,” describing the bond with the visceral force of thug iconography, and then a mid-track segue divorces “thug” from the material, making it about self-respect, pride, identity. The beat changes into a fever swoon of angels, Boogie watching the death of a homie, feeling its approach on his own self, and then stating, “I’m a make a hundred mil one day, but I still be thuggin’ / They can throw a hundred years my way, but I still be thuggin’ / Ain’t no fake shit around my way, I’m still be thuggin’ / Man, I’m still be thuggin’ / I’m still be thuggin’ / I’m still be thuggin’ / Thug life.”

If there’s a mission statement on Thirst 48 it’s “Let Me Rap.” And it’s not Boogie’s statement alone. In “Bitter Raps” Boogie’s “most honest opinion” is the climax, declaring a wasteland of wackness around him as he points the finger at us and tells us he’s killing us. And he is, the instrumental postlude our elegy, we the prostrate. Following that with “Let Me Rap” might be the best 1-2 of any record this year, the latter’s virtuoso verses endearing themselves over one of those simple, perfect key loops and one of those simple, perfect horn accents and that simple, perfect snare ride while Boogie elucidates that he loves women but hates bitches, important to note the part where “Shit then got rocky, uh / That ain’t never stopped me, uh / Mommy played poppy, uh / Poppy played bitch, uh / Left us in a ditch / But somehow we never flinch, uh.” Boogie tells the bitches to fuck off. When he says, “Let me rap…man, real rap,” he’s saying to let him say what needs to be said. Let him be forthright. Let him be true. And those who have nothing real to say, stop adding to the noise. Speak your hearts and have ears to hear when others speak theirs. When Boogie implores, demands, “Let me rap,” he’s speaking for all of us. Boogie’s rap is spitting his spirit into the mic; from that fountain we drink, quenching the real thirst: honest-to-God human connection. And then we do it like we; we all have our own raps. Don’t make us yell silence. Let us live.

Chet Betz

Swans

To Be Kind

(Mute)

François-Dominique Toussaint Louverture was an 18th-century insurrectionist, military official, and head of the Haitian Revolution who worked to liberate the Dominican city of Santo Domingo as well as lead the Saint-Domingue slave rebellion of 1791. A man variously of Spanish and French allegiance yet beholden to no authority but himself, Louverture would eventually be extradited to France by Napoleon Bonaparte, who by the turn of the century was exerting increasing political control under the auspices of the waning French Revolution, assuming democratic control of neighboring colonies and consolidating power in the lead-up to the impending Napoleonic Wars.

Titled in tribute to Toussaint Louverture, the centerpiece track on Swans’ latest magnum opus, To Be Kind, is, in both scope and ambition, every bit the worthy monument to a figure of such humane and progressive sociopolitical achievement. Indeed, “Bring the Sun / Toussaint L’Ouverture“—which very slyly adopts an alternate spelling of Toussaint Louverture’s name, implying in its translation something imminent and unmistakably ominous—is as much sonic hagiography as it is aesthetic deconstruction. Toppling out at nearly 35 minutes in length, the song is not simply composed of movements, but rather of markers and milestones. It begins with the sound of resonating frequencies before a one-chord riff erupts in militant alternation with the metronomic pound of a floor tom. The band soon pulls back into near silence, slowly accumulating momentum via ringing guitar harmonics and rolling percussion as unison vocals summon the arrival of daybreak on the horizon. What transpires, however, is less warmth than leaden chill, as frontman Michael Gira spends the next ten minutes incanting in a foreign tongue, invoking the track’s eponymous subject for an improvisatory bit of soothsaying as the band trots steadily in their leader’s wake. The song culminates, inevitably, in a hurricane of distortion and aural destruction. It may be the best thing Swans have ever recorded. It’s certainly the most daunting. Did I mention the horse sample?

Scale aside, “Bring the Sun / Toussaint L’Ouverture” manages to play as a kind of microcosm of both Swans Mk2 and Gira’s now thirty-year artistic arc. It builds in industrial force not unlike the band’s early records, settles into a narcotic midsection resembling their mid-‘90s work, starts speaking in a familiar yet distinctly different sonic language (Angels of Light), before finally reemerging more confident and powerful than anyone could have ever imagined. And it’s this confidence, bred from a seemingly insatiable sense of untapped creative possibility, which has resulted in a trio of bulletproof albums, each one more improbably ambitious than the last. Swans have never been ones for subtlety or hedged bets, but even still, the sheer structural and thematic proportions of the band’s recent work is nothing short of staggering.

How then to top—let alone equal—the potentially career-swallowing breadth of The Seer (2012)? The answer’s embedded in the infrastructure of To Be Kind itself, a record somehow both longer—spread out over six sides and two-hours—and more diverse and dynamic than in its predecessor. Opener “Screen Shot” pivots on a swiveling, Shellac-like riff, as Phil Puleo’s drums, simultaneously nimble and numbing, hammer in the margins between the six-string interplay. It’s a tactic implemented and exploited throughout the record, helping to define the severely minimalist topography of the record in nuanced contrast to The Seer’s at times overwhelming aural claustrophobia, opening in the process breathtaking chasms within compositions which are otherwise built on arrangements bombastic enough to make Billy Corgan blush—monuments to an elegy, indeed. These brief instances of breathing room allow for voices both literal (guest vocals from the three-woman army of St. Vincent, Cold Specks, and Little Annie) and figurative (the specter of Kirsten Dunst haunting the hypnotic “Kirsten Supine”) to infiltrate and compliment the band’s precision attack, working together to reinforce what was already a united front. That this rigorously integrated conceptual approach would then echo Gira’s holistically mapped spectrum of human compulsions (“We seed, we feel, we need, we fight, we seal, we cut, we seek, we love…”) on “Some Things We Do” makes perfect sense. This is an album as draining and dramatic as life itself.

Jordan Cronk

Flying Lotus

You're Dead!

(Warp)

Fun fact: RuPaul first did drag as an act of punk rock. For RuPaul, for Flying Lotus, the world is a construct, self is an illusion, death is a race—and a friendship that occasionally, maybe, resembles the asshole Duck Hunt dog. It’s a corner you turn in your life when you realize just how great a friend and memory that asshole dog laughing at you turned out to be.

Like RuPaul transitioning now from man to woman, from sailor to glam-ed out diva, Steven Ellison races through genres, features, and all the feels on his video-game infused epic You’re Dead!—an album that equally smacks of jazz, bangers, and oozing makeout tracks. From smooth sax and guitar wheedling in “Turkey Dog Coma,” to belly-of-butterflies jazz track “Moment of Hesitation,” fluttering on suspended cymbal whisks, You’re Dead! transitions with pure agility and motion. That corner you turn, and that speed Ellison’s picked up, is loss.

In death, people are gone easily as a button coming loose. With their loss are the known aspects of self that to your terror are just lost and gone from you or the world, having crumbled away like great chunks of snow from icebergs. It cuts you down to a slim shape that seemingly, simply, cuts right through time. What was so ancient, and so compressed with importance, just tumbles off your self and away. Enough falls away from you, and speed is what’s left. Having had significant loss to shoulder and cut away, Ellison in You’re Dead! faces it in every aspect: certainty of a death; certainty of all deaths.

Friendships are great deaths, and in mortality itself is an unanticipated warmth touched upon as it wildly uncoils. Despite the insidious magic of it: the racing along, the pursuit at a breakneck clip, the speed of it can be a friendship in what is otherwise an uninvited machine. Velocity is the tool, the key to shifting death to friendship. Turning the building unacceptance into a curiosity—and a quizzical drilling of the mind into that secretive landscape.

Improvised and cuttingly sporadic, even the percussion is resolved to a bold lack of return. A hectic chase, it is transformative of the impending—the wildly uncoiling—mechanics of life’s ending or of, just: abruptness. In its frenetic looping, is a wild condition of unrest, failure, death, and high scores.

There is time, sure, to quiz and to drill—but there is an abandon of inspection, of dwelling. It is a game; it is a friendship; it is a condition in great motion. And it laughs at you as you’re staring it in the face.

Kaylen Hann

Adult Jazz

Gist Is

(Spare Thought)

The debut record by Adult Jazz is, like an overstimulated Ivan Reitman joint, a heavy-handed summation of a lot of barely related items: post-rock; parables; compulsiveness; koans; radio jazz; smooth jazz; obsession; phonemes; assonance; sad Adam Sandler; extraneous vowels; Les Savy Fav and Animal Collective; hair; hands; hops; silverware; civility; and, perhaps more than anything else, unconditional love. These the band treats like burdens, their record an account of accepting said items or trying to wiggle out from under them. An almost literal interpretation of their chosen moniker, what is Adult Jazz but exactly that: fussy music for ambient people—trapped, obligatory, and tapped into a dark core of existential angst.

And so, theirs is this. This is a gist of cosmic turmoil, a boiling down of dimensions, a litany of moments that exist, then exist, then exist, like riffs observed in the same way subatomic particles are measured—grooves the singularity, a song called “Am Gone” like goth bebop, all mope, all nostalgia, all catchy, chattering nonsense. This is “Springful,” a sound that, lichen-like and spindly, begins to own a room by defining it. These are vocals and snares and guitars and other elemental waveforms that rarely sit still, yet seem completely at ease with what they are, who they are, ostensibly giving zero fucks but steadfastly keeping score. These are base functions, foundational motions. This is the lithe stuff of maturity, of responsibility, of the hard work required to arrange matter in this way, of this caliber, to adhere to an ordinary life; a base life; a functional life; a foundational life. This is real grown-up anger, which means this is the stifling acceptance that for every one thing in one’s control, there is a universe of unknowable chaos to endure, and so Adult Jazz is like listening to the itching sensation of struggling to control one more measly thing in one’s increasingly obvious meaninglessness, to commit to something and in that commitment to make a life, to actually create it from squishy, squidgy empirical particles, and to raise it and to work hard for it and to hope to realize one’s best self for it, and then to understand that at some point in that life’s life you relinquished all worth of your own, and thus such chaos is born anyhow. This is a debut album with impeccable ineffability. This is a good record for dinner parties. This is the gathering of young parents for food, a difficult night to calibrate, a time spent together half in conversation, half in anticipation of “Spook,” the soundtrack to children going to sleep, flecked with rust and pain, to a mouth tensed, closed mightily to the intervention of a tiny toothbrush, to the first once upon a times of buoyant bedtime stories, but whispered, giving these children dreams of portent, all so that, finally, the young parents can return to the family room so that things can start to get a little weird—“Idiot Mantra,” and the ensuing loosening of inhibitions, the retrieval of djembes from the hall closet and dried weed from the basement, the startling shake of “Be A Girl” ruining the séance, the ritual in which everyone gathers to dredge the long-dead spirits of earlier selves who never kept score on the amount of fucks given—before, inevitably, mortality, martial and unforgiving, returns bras to owners and pants to legs and children, snoozing, to carseats, this “Bonedigger” a taunt and an admission, a song of acceptance, or something. This is a reiteration of something I said last year about a record that is utterly different but that carries similar weight, in which I claimed that fucking is a privilege, when what I really meant was that fucking is always a breach, because such is penetration, and penetration demarcates is-ness from is-not-ness, and this is how Gist Is trysts with physics: by stabbing at silence, first clumsily, and then with bliss, each note, each thrust, each coo pregnant in the knowledge that such motion is a gift, and every bit of inertia earned, and one’s occupied space in this reality a negotiation of others’ space, of others’ responsibilities, of others’ abdications. This is like Peacock Lane, the small street near where I live, City-renowned for elaborate Christmas lights, occupied by thousands of people each night from December 15th until too long after Christmas, and providing nothing in the way of anything that distracts from the absurdity of driving 45 minutes from the ex-urbs to walk no more than 300 yards to look at truly fucking unexciting multi-colored bulb arrangements, a street which requires policing care of heavy flashlights, a street which requires manpower and whistles and temporary crosswalks, a street that belongs to no one but claimed by congestion, as if such a sinusoidal word were acceptable to describe the simple act of individual human beings doing nothing more than accepting a place in line, a pace in line, and a cognizant notch in the churning assembly of stupid light-gawking, as long as there is a flask in one’s breast pocket and the kids have their candy canes or whatever. This is the question a toddler asks you about why you don’t have a house this big, or lights this elaborate, or a giant inflatable snowman, the toddler’s voice tinged with doubt about your capabilities in raising it and working hard for it, and this is your answer: to ignore the toddler. And to stare at the police officer at the foot of the crosswalk who ignores the flow of foot traffic and instead stares away from you, down the street, his back to the lights, into the dark, which holds nothing but black space, black matter, and a police officer’s one lone acknowledgement that there is nothing more to this than, simply, more of this.

Dom Sinacola

Ian William Craig

A Turn of Breath

(Recital)

I am obsessed with old melodies. I’m only twenty-one, but I hoard them like dusty, antiqued attic shit, stuff that accumulates in value but loses the currency of life. I guard old songs like anyone guards something they have no use for: I fear the death of it and everything else, but I’m proud, knowing that no one else had the same throughline that I did—that the most arbitrary of sounds is important to my history.

I still hold Travis’ The Man Who (1999) close, but it’s far away by now—it’s travelling into the distance in the car we used to take family trips in. Earlier this week, I listened to a pretty average Maps & Atlases song on the train home from work; I ended up playing the vocal melody from its second verse twenty times, as many as the three-minute commute from Leeds to Burley Park station allows. I held down the reverse button over and over, for a mere second at a time, in order to hear the same thing for as long as I could. I love that verse, but I wanted it to stay. There are moments in music so good that I wish they were a photograph I could see every day. Though they might age, I would give anything for them to stay still, held to a fixed point that would just be there.

My favourite record of 2014 offers the complete opposite. It has never been in a place, though I have tried to fix it to a few. When I listen to Ian William Craig’s A Turn of Breath—which is something I have done daily for the last six months, thank you very much—I feel like nothing is ever still. I’m stuttering in the air, falling over clouds, crumbling in water. I am an accident of transcendence, and I’m more prone to change than I have ever been. Call it decay, call it cells replacing; everything is turning over. It’s my favourite record of the year, but everything about it suggests the opposite—that any attempt at asserting singularity, of this being one album on a list of ten, is a fool’s errand.

It’s not actually called A Turn of Breath, by the way; on the record’s spine, it’s “A Turn of Breath”. Those quotation marks reference an updated memory. They suggest that Craig is lifting from his record to make a new one every time you spin it. “A turn”: for each vocal, for each melody, a new divergence. It might sound like a joke, and at this point I’m verging on self parody whenever I talk about this record (and yet my opinion is still changing and intensifying, even at the time of writing), but I’ve actually heard this music on three different 12” records. I can compare each of them. All provided new experiences, like differently useful elements. Each setting intruded on Craig’s music, and each time his music detached from that setting. And each experience was a part of this thing I have tried and failed to make my definitive, non-pluralised moment of 2014.

What Craig does is supreme and complex, but actually: he sings next to tapes. There’s a lot of distortion and analog drone and acoustic balladry, and that’s how I got into this thing—the beautification that’s sketched around the transience—but A Turn of Breath is an opera singer belting it out on the world’s tiniest stage. Such grandstanding should be for ancient, everlasting history—or you should make a night out of it, in some tall opera house—but Craig dismisses his sounds every second. Motifs are repeated to articulate their leaving, the murmured melody that opens “TEAC Poem” fed through Craig’s reel-to-reels like the dust of the dead, floating upwards and being forgotten.

Forgetting is remembering, though. This year, I’m thankful to Dirty Beaches, Mary Lattimore and Christina Vantzou, because they all filled empty tunnels and forgetting places with discovered sound. But A Turn of Breath has been my guide: its loops, not disintegrating, but reincarnating; its droning spaces, investigating the difference between repetition and renewal; and Craig’s voice, profound and resilient, but fragmented into dividing multitudes. Something too beautiful and full of life to actually be some thing.

I would like to frame A Turn of Breath. But it would travel outside of the borders, because all of Craig’s motifs and lyrics are ellipses. This record reminds me of the times I’ve looked at a picture or a painting, or watched a scene from my favourite film, and felt like some integral detail has changed. I so often have these moments, where I swear a different colour was on the canvas, a different word was used in dialogue. It’s another kind of déjà vu, one that forces us to update our memories and accept their vulnerabilities. And fuck it, A Turn of Breath is about letting go: don’t hoard, don’t look sentimentally to your favourite moment in time. It will change. Let it turn over.